Pilar Ponzán Vidal

Women in the anti-totalitarian resistance

When resistance is discussed, it is always invariably associated with the movements that emerged in Nazi-occupied Europe during the years of World War II (1939-1945). A resistance that materialized in multiple forms, modalities and degrees of involvement and in which women took an active part. A participation that, despite the invisibility that women have historically endured, is being increasingly studied and valued.

Women who were part of the French resistance are a good example of its nature. The life courses of many Spanish women who settled in France, be it for personal, family or political reasons, was marked both by the uniqueness of the country they settled in and by the outbreak of World War II. At that time, they all got involved to face the Nazis. Both their actions and their commitment illustrate the role –largely unknown and silenced during many years– that women played in the fight against Nazism in France. The fact that, in most cases, they were not French citizens, and the widespread lack of knowledge concerning their struggle in Spain, caused the importance and recognition of their role to be significantly underestimated.

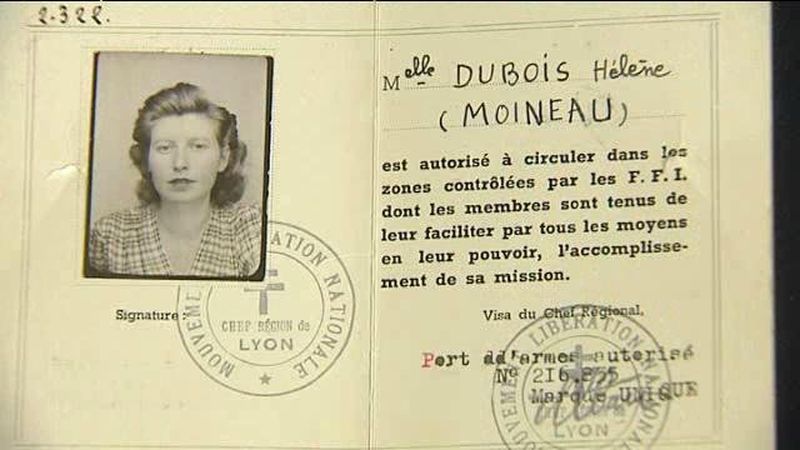

In spring 1940, the Allied defeat in the Battle of France caused France to be divided into two zones: one occupied by the Nazis and the other controlled by the government of Marshal Pétain. As a result of General De Gaulle’s call for French young men to join the Resistance that was being organized from Great Britain, thousands of young people took the path to North Africa. At the same time, the Resistance began to be organized in France with the creation of the first clandestine struggle groups. The main activities of Resistance networks involved aiding prisoners of war and taking part in information, evasion and sabotage actions. Their actions became an indispensable help to the allies. The networks recruited secret agents, men and women, mostly civilians, that operated under code names and used to report on German activities, ensure the rescue of those who wanted to flee Europe, organize clandestine air and sea operations, communicate by radio, carry out sabotage, etc.

The setting up of these networks was the result of civil and military resistance. They were supported by the social fabric of the country they were in and depended on the coordinated action of many people who had started to be engaged on an individual basis. In most cases, both their origins and organization were of great magnitude, since they consisted of a worldwide movement connecting very distant places and countries. In some ways, the history of resistance networks is the history of the underground war against the Nazis.

Resistance networks can be classified into three categories: action, information and evasion. They were mostly promoted by the intelligence services of the allied countries and by the so-called Free France movement (followers of De Gaulle). For their part, the so-called evasion networks were clandestine organizations that indistinctly brought people and documentation from anywhere in Europe to Spain and/or Portugal. These organizations became the only way to fight the invader.

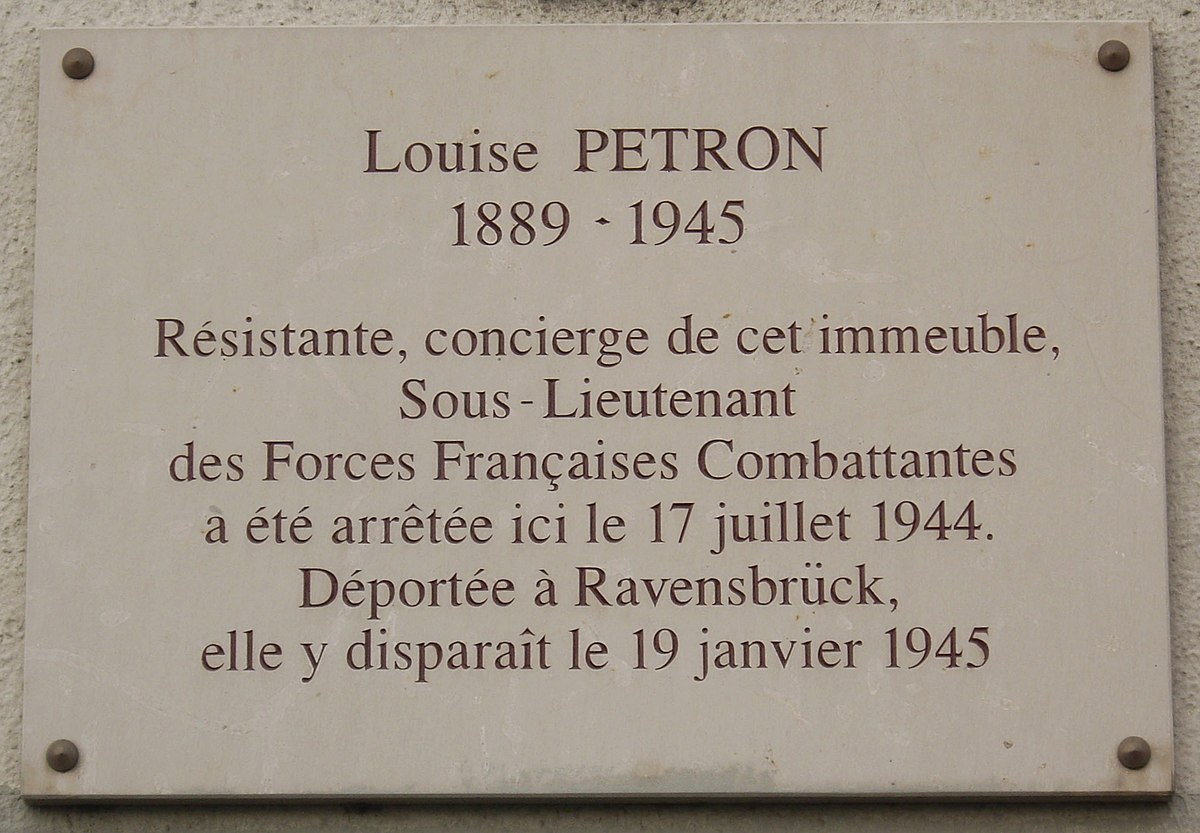

These networks included a large group of agents who covered, in a coordinated and hierarchical manner, the different functions of the machinery that made them operational: mail, transport, accommodation, smuggling, etc. It was a wide and complex chain that needed to work seamlessly to be able to successfully accomplish its missions. Guides were an essential part of it, but as a matter of fact, the structure of the networks was also made up of links and couriers as well as by the owners of the houses where the resistance fighters took refuge. Amidst this complex machinery, women played a key role. They were leading players, especially in support, mail and information missions, and their activity was also equally risky. In their missions they faced the greatest of dangers, for an arrest usually meant the shooting or deportation of the agent.

An indisputable proof of the importance of resistance networks can be found in the fact that in France, from 1945 on, and after the establishment of a National Approval Commission, the Forces Françaises Combattantes (FFC) approved a total of 268 networks of which thousands of people had been part, including hundreds of women.

It might come as a surprise that in the 1940s, amidst a world war, a woman would become involved in a structure as complex and dangerous as that of a resistance network. Despite the dangers women faced in these organizations, their presence was certainly significant and played a rather prominent role. Research on the subject has uncovered for example the unique story of Pilar Ponzán (Huesca, 1906– Zaragoza, 1999), sister of the anarchist leader Francisco Ponzán, who was at the head of a very active group that cooperated with several networks, including the British Pat O’Leary network or that of Alfonsina Bueno Vela (Moros, 1915– Toulouse, 1979) who cooperated also with the Ponzán group and ended up being deported to the Ravensbrück and Mauthausen camps.

In a more universal context, the history of the Comète network, founded by the Belgian citizen Andrée Eugénie Adrienne de Jongh, should also be highlighted. De Jong facilitated the escape and rescue of numerous airmen of the Allied Air Force through the escape routes that led to Spain on the Atlantic side. New research has also uncovered the life story of Carme Gardell Garcia (Setcases, 1891– Ravensbrück, 1945) who was at the service of the Darius network; and that of Generosa Cortina Roig (Son, 1910– Toulouse, 1987) as an important part of the Belgian Jean network and later of the so-called Françoise network. Likewise, Roser Fàbregas Vilà, married Fluvià (Prats de Lluçanès, 1900– Perpignan, 1983), Carmen Aguilera Pérez, married Zapater (Almeria, 1912) and Braulia Cánovas Mulero (Alhama de Murcia, 1920– Barcelona, 1993) also took an active part in the Alibi network. And many others. Most of them were arrested and deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. Their lives were marked by a strong ethical and ideological commitment.

As further research based on the approval records concerning the membership to the Resistance networks makes progress, the participation of a significant number of Spanish women in them is exposed, as is the remarkable work they carried out both in cities and in missions aimed at distributing propaganda and/or welcoming resistance fighters, as in the case of Felicitat Gasa (El Pont de Suert, 1905– Landon, 2000) in Bordeaux; or in support of the Maquis, as in the case of Herminia Puigsech (Mataró, 1926– Verhnola, 2013), Conxita Grangé (Espui, 1925– Toulouse, 2019), Elvira Ibarz (Mequinenza, 1891 – Toulouse, 1953) and Maria Castelló (Mequinenza, 1914– Paris, 1945), who served as links with the Maquis in the French department of Ariège; and finally also as couriers, in the custody of documentation or at the direct service of the evasion networks in the towns around the Pyrenees area. The fact that those who survived deportation did not return to Spain has heightened their invisibility despite the acknowledgments they received in France.

For its part, in Spain, the resistance to the Franco regime also had an obvious female component, although in a numerically less significant dimension than the one prevailing in Nazi-occupied Europe. The repression that the Franco regime imposed against its republican enemies was relentless, with thousands murdered, imprisoned or used as forced labour. During the 1940s, Spain was an immense prison where the population lived in total fear.

While World War II shifted in favor of the allies, in Spain, although silenced, women continued fighting against the Franco regime by taking part in the armed resistance. This is the case, among others, of Manuela Díaz Cabezas (Villanueva de Córdoba, 1920–2006), Esperanza Martínez García (Vilar del Saz de Arcas, 1927), Enriqueta Otero Blanco (Castroverde, 1910– Lugo, 1988) and Cristina Zalba Rodis (Barcelona, 1909– Castellfollit de la Roca, 2001). All the women above –and many others– endured a harsh repression against their relatives and suffered the direct brutality of the Civil Guard, the security force in charge of suppressing resistance in rural areas. Franco tried to strip this resistance movement –the guerrilla– of its political character by placing it in the realm of common crime.

The course of their lives has never been given the recognition granted to the women who played a leading role in the French Resistance. In all cases, giving a proper value to their actions and biographies and paying tribute to their memory is a task yet to be accomplished.

Josep Calvet

Historian

Bibliography and video reference

- Douzou, Laurent-Yusta, Mercedes (direction), La Résistance à l’épreuve du genre. Hommes et femmes dans la Résistance antifascite en Europe du Sud (1936-1949). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2018.

- Callejas, P, (direction) (2023) Heroínas Olvidadas. Españolas en la resistencia [Film; online video] RTVE Somos Documentales : https://www.rtve.es/play/videos/somos-documentales/heroinas-olvidadas-espanolas-resistencia/6834608/

- Calvet, Josep, Pallaresos deportats als camps de concentració nazi. Tremp: Garsineu edicions, 2022.

- Gaspar Celaya, Diego. Combatir sin armas. Mujeres españolas al servicio de la Francia combatiente, 1940-1945 en Historia Social, nº 97, 2020, p. 135-155.

- Planagumà, M, (direction). (2023) 508 dies [Teaser]. Amical d’Antics Guerrillers de Catalunya : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qL3mCB8YRK0&t=3s