Women in the Democratic Opposition in Poland, 1970s-1980s

The Solidarity revolution, as the complex process of the emergence of a mass resistance movement against the communist dictatorship in Poland in the early 1980s is often called today, is above all a story of people, their personal motivations and their determination. The democratic opposition that developed from the mid-1970s and paved the way for the revolution was a mosaic of very different views, which was composed of almost all the traditions of the pre-war Polish political scene. One glaring exception was the absence of the tradition of the Polish feminist movement. However, while those fightng for better living conditions and later for civil liberties did not see the need to highlight the gender issue, the presence of women in the structures of the individual organisations that formed the opposition movements was noticeable in almost the entire country, albeit with varying degrees of intensity.

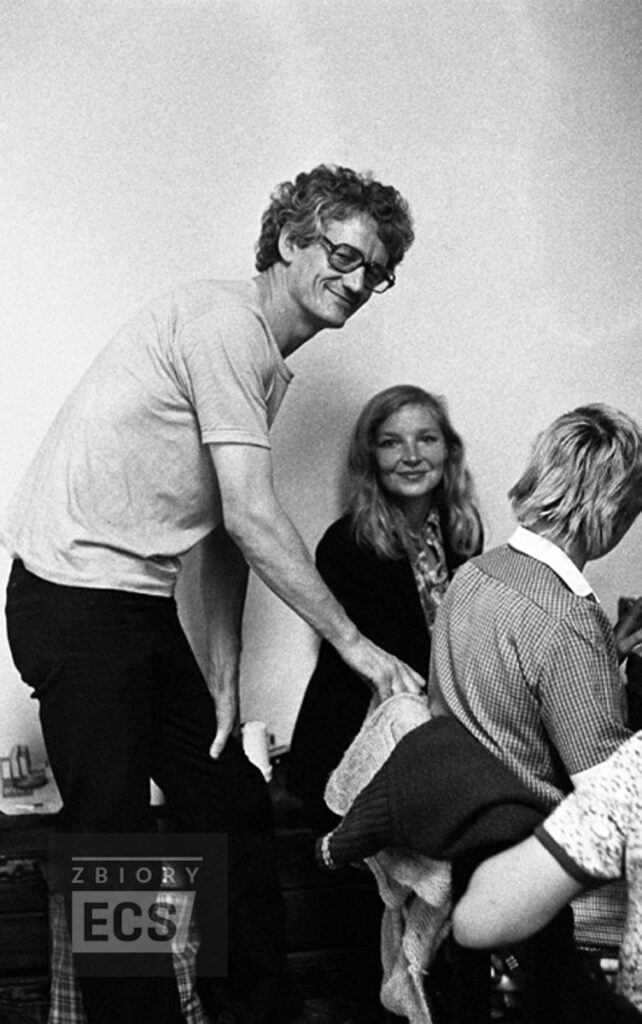

Although the issue of women in the democratic opposition has not yet been the subject of a comprehensive monograph, we know that the degree of women’s participation was mainly influenced by various cultural factors. In the Warsaw intelligentsia underground, women accounted for just over half of all those involved in the movement, whereas in the smaller towns of southern and eastern Poland the figure was only around 17 to 25 per cent. Importantly, however, women made up about half of the members of the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union called Solidarity, which was legally established in August 1980 and had some 10 million members. While female members of the legal union are relatively ‘countable,’ those involved in the underground often had problems with self- identification. Many of the women involved in the opposition did not feel that they were its formal members:

‘I didn’t formally belong to anything,’ said one activist, ‘and nobody asked me to; I participated in discussions, took minutes, distributed the press, helped prepare meetings; … I wouldn’t call myself an activist – when help was needed, I helped.’1

Most women were involved in the movement in large cities, where academics played an important role. Although Anna Walentynowicz, an overhead crane operator at the Gdansk shipyard became the symbol of women’s involvement, we now know that female workers were rather marginal in the opposition. Female teachers, lawyers, doctors and nurses, engineers and civil servants predominated. There were far more middle-aged women, over 38, than young women.

The presence of these groups was particularly noticeable in the openly active KOR (Workers’ Defense Committee), the main opposition organisation before the Solidarity era, which supported workers repressed by the authorities in 1976. This elite group included three women: the lawyer Aniela Steinsbergowa, the actress Halina Mikołajska and the writer Anka Kowalska2.

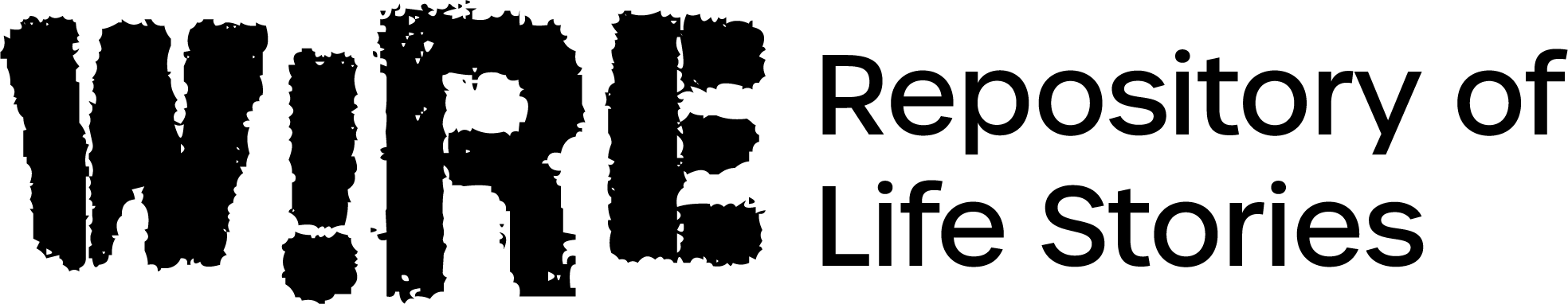

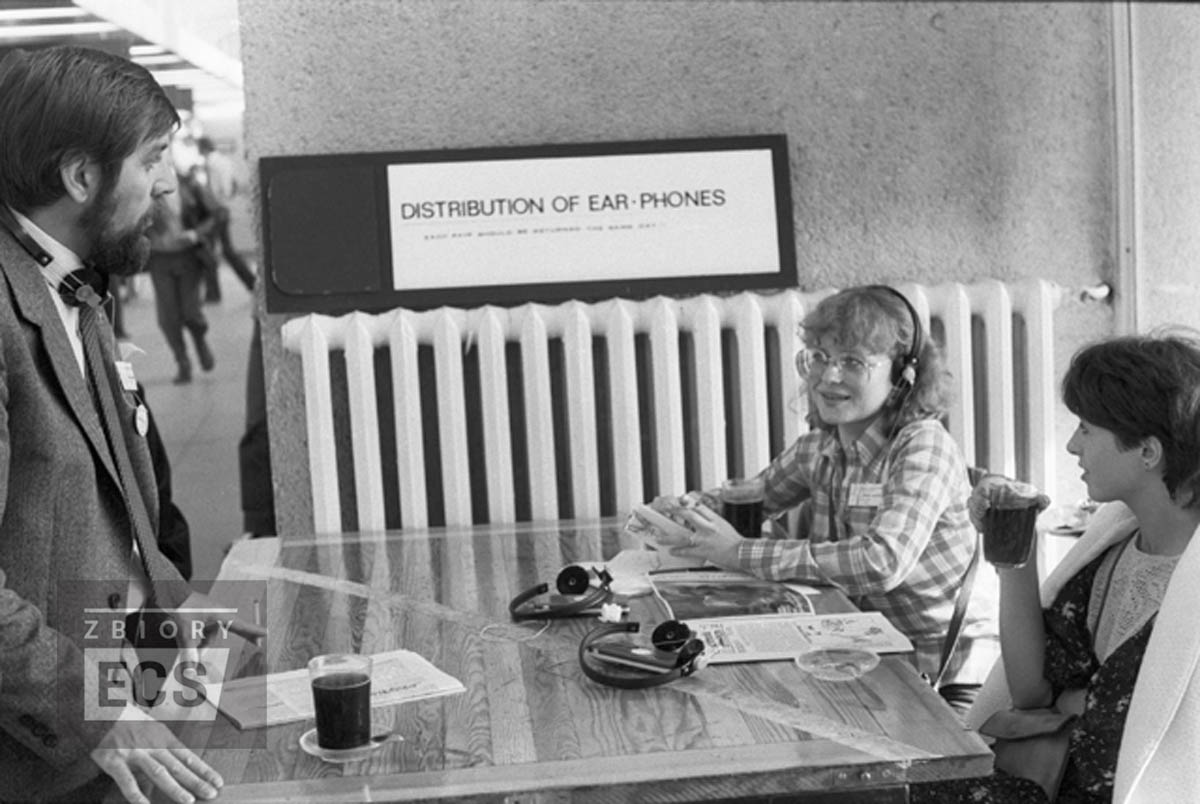

However, as the events of August 1980 on the coast played a decisive role in the emergence of the opposition, it is the presence of women in these strikes, in negotiations with the authorities and in the creation of free trade union structures that historians of women’s history tend to focus on.

Although the strikes were largely dominated by men working in the shipbuilding industry, an important role was played by prominent women activists with, incidentally, very different political views: Anna Walentynowicz, Joanna Duda-Gwiazda, Alina Pieńkowska, Henryka Krzywonos, Ewa Ossowska and others.

The Polish centre of opposition activity with the highest share of women was the “Tygodnik Mazowsze” publishing centre, which grew out of the KOR tradition, and the KOS publishing house. Helena Łuczywo, Joanna Szczęsna and Anna Dodziuk were instrumental in the creation of the most important magazine in the Polish underground press. And since “Tygodnik Mazowsze” was an organ of the movement’s authorities, it is not surprising that Łuczywo and Szczęsna were present at meetings of Solidarity leaders. The editorial staff of “Tygodnik Mazowsze” shared a unique experience of community life in the underground. Helena Łuczywo recalled that until 1983, when Joanna Szczęsna was arrested and when she decided to come out, they worked and lived in one flat. And since they were hiding from the police and the Security Service, they had to keep changing flats.3

The activities of female oppositionists did not differ significantly from those of their male colleagues. With one exception, albeit a significant one: women were more likely to make their flats available for opposition activities, which must have complicated their family lives enormously. ‘We were young people,’ one of the female activists recalled, ‘none of us had our own flat, the Samsonowicz family, especially Hala [Halina Samsonowicz] was an extremely hospitable person, she put up with our invasions of her one-room flat, she had two children, she behaved heroically, risking so much: her role is crucial, she made it possible for us to meet4.

If there were so many women in Warsaw alone, why was it believed that they were invisible and therefore had little participation and influence in the functioning of the union? This was mainly due to the absence of women in the leadership of the movement. The authors of the book Konspira. Rzecz o podziemnej “Solidarności” [Conspiracy: The History of the Underground Solidarity] ironically noted that, even before 1989, organisational Solidarity documents may read like the underground was as a ‘men’s monastery’. There were, of course, some exceptions. The main exceptions included: Ewa Choromańska, Ewa Kulig and Zofia Romaszewska, who, together with her husband, was a very active member of the KOR and undoubtedly influenced the decisions of the movement’s leaders. Paradoxically, it was easier for women to enter the leadership structures after the declaration of martial law and the banning of Solidarity on 13 December 1981 and the subsequent internment of the vast majority of trade union leaders, who were men. However, this did not mean that women were not on the lists of internees. Almost 400 women were interned and taken to the centre at Goldapia, on the border with the USSR.

The problem of the absence of women in the democratic opposition in the collective memory in Poland became part of the public debate relatively late, thanks to the publication of the American journalist and feminist Shana Penn, who travelled to Central and Eastern Europe in the early 1990s to talk to opposition women in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. In her view, despite their numbers, the women involved in the Solidarity revolution were invisible in the movement, their awareness of gender issues was low, and they saw the focus on women’s rights issues as self-serving. This, she argued, had immense consequences for women’s rights in Poland and their presence on the political scene after 1989. Her acclaimed book, which laid the foundations for research on gender in the opposition, was published in 2003 (Polish version) and 2005 (English version).

However, if we focus on interpreting women’s presence in the opposition in the context of their experience of the dictatorship era, the question of their presence in the political world becomes much more complicated. All the more so because the regime guaranteed the possibility of emancipation through work and education, but did little to activate women politically, despite the long tradition of women’s full political rights (since 1918). Thus, we can assume that the success of women’s involvement in the opposition can be measured (from the perspective of gender history) as much by the degree of actual activation of Polish women as by the movement’s ability to produce numerous and articulate female leaders with clear political ambitions.

In the first case, we can even speak of an over-activation of women, especially considering the whole range of social obligations to which they were subjected (motherhood, caring responsibilities, household management, and professional work). In this way, various underground organisations and the legal and banned Solidarity became the ‘school of life’ for women, who in free Poland helped to create the social elite as journalists, creators of new education, and activists in local governments.

In the second case – taking over the real political helm – there was little chance of success. Solidarity functioned in exactly the same social and cultural fabric as the Communist Party, and this culture did not give women political experience or teach them the need to take on political responsibility, especially in a fiercely competitive environment. Such an education could perhaps have come with an independent feminist movement, but there was no place for it in the Polish People’s Republic.

References:

- Kenney P., The Gender of Resistance in Communist Poland, The American Historical Review, Volume 104, Issue 2, April 1999, Pages 399–425, https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr/104.2.399

- Penn S., Solidarity’s Secret: The Women Who Defeated Communism in Poland, University of Michigan Press 2005.

- Płeć buntu: kobiety w oporze społecznym i opozycji w Polsce w latach 1944-1989 na tle porównawczym [The Gender of Rebellion: Women in Social Resistance and Political Opposition in Poland in 1944–1989. A Comparative Study] eds. N. Jarska, Natalia and J. Olaszek, Warsaw 2014.

Movies:

- Solidarność według kobiet [Solidarity According to Women], Dir. Marta Dzido and Piotr Śliwowski

www.youtube.com/watch?v=fQzNeQCLYB4

2 P. Perkowski, Droga do władzy? Kobiety w polityce [A Path to Power? Women in Politics] in: Stańczak-Wiślicz, M., Perkowski, P., Fidelis M., Klich-Kluczewska B. Kobiety w Polsce 1945-1989 : nowoczesność – równouprawnienie – komunizm [Women in Poland 1945-1989: Modernity – Equality – Communism], Krakow 2020, pp. 106-107.

3 J. Olaszek, Rola kobiet w warszawskim podziemiu lat osiemdziesiątych [The Role of Women in the Warsaw Underground of the 1980s], in: Płeć buntu: kobiety w oporze społecznym i opozycji w Polsce w latach 1944-1989 na tle porównawczym [The Gender of Rebellion: Women in Social Resistance and Political Opposition in Poland in 1944–1989: A Comparative Study] eds. N. Jarska, Natalia and J. Olaszek, Warsaw 2014, pp. 295-296.

4 4 B. Kijewska, Kobiety w opozycji demokratycznej na Wybrzeżu Gdańskim… [Women in the Democratic Opposition on the Gdańsk Coast…], p. 222.

1 B. Kijewska, Kobiety w opozycji demokratycznej na Wybrzeżu Gdańskim w latach 1976-1980 [Women in the Democratic Opposition on the Gdańsk Coast 1976–1980], in: Płeć buntu: kobiety w oporze społecznym i opozycji w Polsce w latach 1944-1989 na tle porównawczym [The Gender of Rebellion: Women in Social Resistance and Political Opposition in Poland in 1944–1989: A Comparative Study] eds. N. Jarska, Natalia and J. Olaszek, Warsaw 2014, p. 221.

2 P. Perkowski, Droga do władzy? Kobiety w polityce [A Path to Power? Women in Politics] in: Stańczak-Wiślicz, M., Perkowski, P., Fidelis M., Klich-Kluczewska B. Kobiety w Polsce 1945-1989 : nowoczesność – równouprawnienie – komunizm [Women in Poland 1945-1989: Modernity – Equality – Communism], Krakow 2020, pp. 106-107.

3 J. Olaszek, Rola kobiet w warszawskim podziemiu lat osiemdziesiątych [The Role of Women in the Warsaw Underground of the 1980s], in: Płeć buntu: kobiety w oporze społecznym i opozycji w Polsce w latach 1944-1989 na tle porównawczym [The Gender of Rebellion: Women in Social Resistance and Political Opposition in Poland in 1944–1989: A Comparative Study] eds. N. Jarska, Natalia and J. Olaszek, Warsaw 2014, pp. 295-296.

4 4 B. Kijewska, Kobiety w opozycji demokratycznej na Wybrzeżu Gdańskim… [Women in the Democratic Opposition on the Gdańsk Coast…], p. 222.