The Greek Resistance as Female Empowerment (1941-1944)

“Yesterday’s animal became the subject of history. Yesterday’s pariah became a citizen with rights”.

Eleni Kivelou-Kamoulakou, EPON

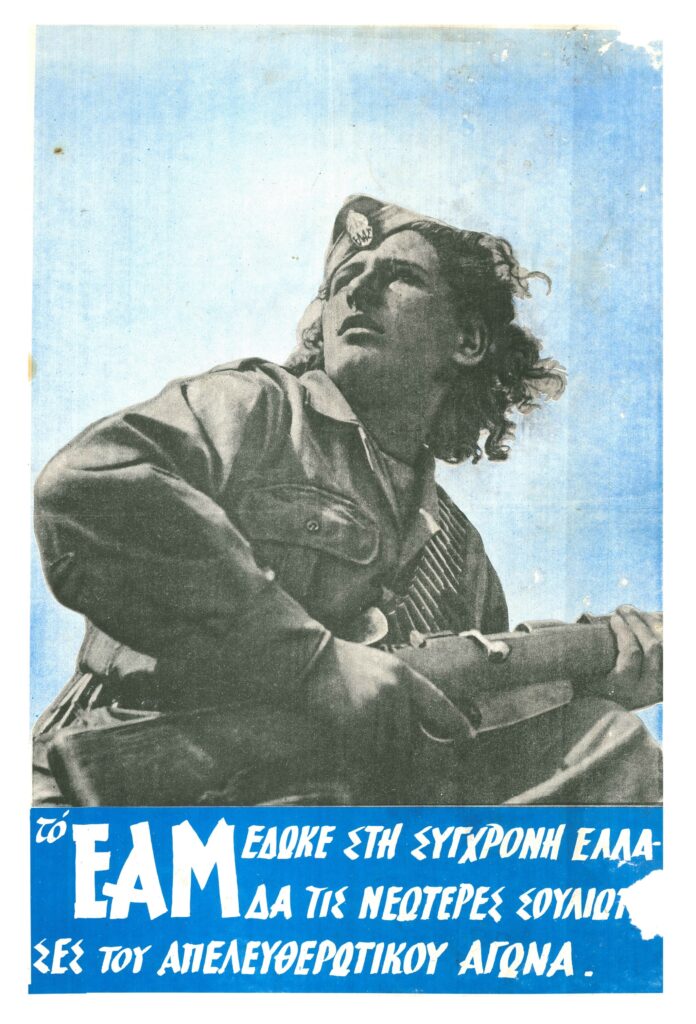

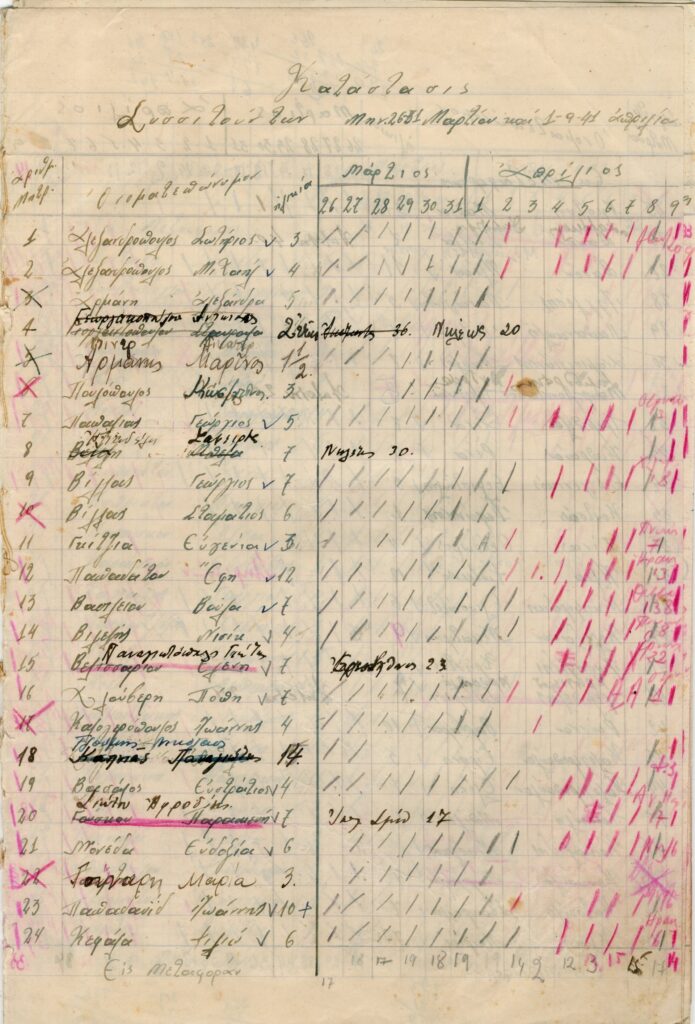

The Second World War and the Axis Occupation (1941–1944) changed Greek society profoundly. The extraordinary conditions created by the Occupation radicalized a large segment of the destitute population and gave the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) the opportunity to lead one of the most massive resistance movements in occupied Europe. During the Occupation, more than one third of Greek women participated in the political, cultural, and military organizations of the Resistance, even though they had no political rights. In concrete, it is estimated that women made up 45% of the National Liberation Front (EAM), the largest resistance organization in Greece; in National Solidarity (EA), a nationwide solidarity organization affiliated with the EAM, almost two-thirds were women; women made up 50% of National Panhellenic Youth Organization (EPON) members; and 10% of all reservists participated in the women’s platoons of the National Popular Liberation Army (ELAS).

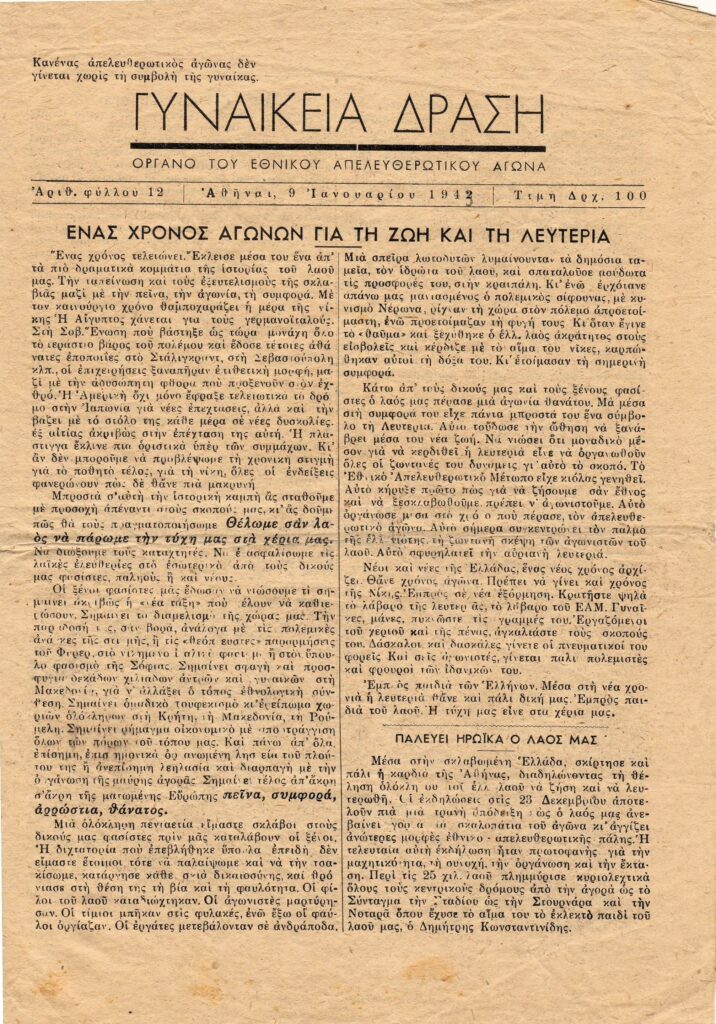

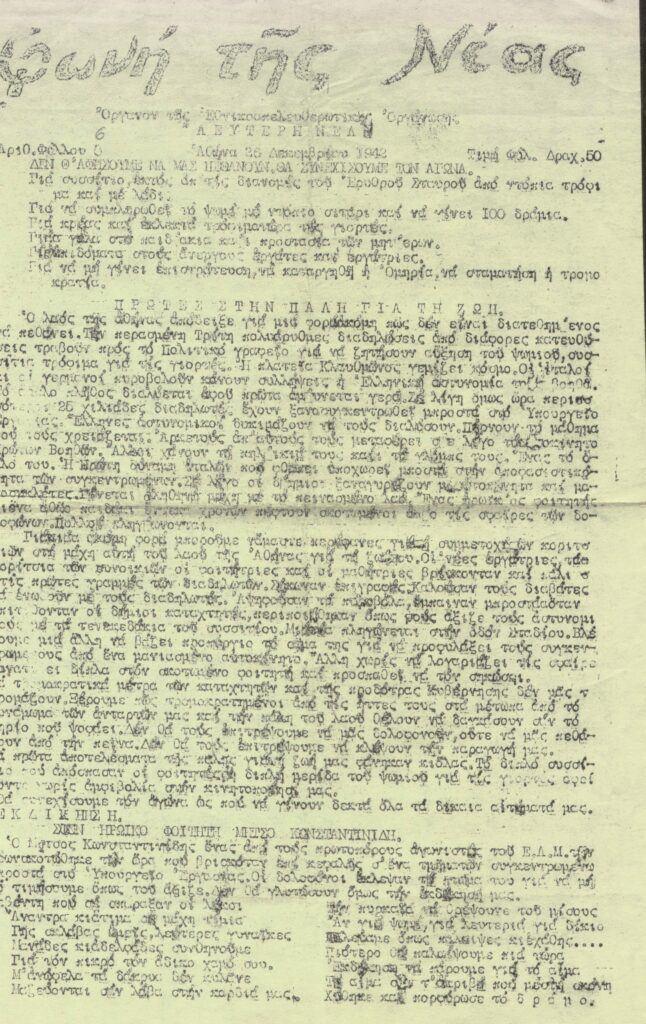

We could distinguish the women’s participation in the Resistance in two phases. During the years 1941-1942, they participated by extending the role of housewife and mother. It was considered natural for them to take the lead in the mobilizations for survival by supplying food and shelter, extending the traditional action of women within the home to take care of other family members, to society, to the extended family, the nation. Women took also on writing slogans on the walls, opening schools and kindergartens, taking up fundraisings, caring for the persecuted, the imprisoned, the victims, offering the guerrillas clean clothes, woolen socks, flannels, sweaters, food and moral support in letters, operating hospitals, infirmaries, and first aid stations, while their contribution in the field of entertainment and civilization was equally important. The weeping of the dead and the funerals were also converted by women into resistance events.

From the spring of 1943 until the end of the Occupation in 1944, women were militantly present at the big demonstrations, they were mobilized collectively and organized for the release of prisoners and hostages, they hid the English combatants, they guarded the village, acted as liaison officers, and carried out espionage and sabotage operations. Women took also part in the clashes with the occupation forces and there were many of them among the dead and wounded. Thus, the most massive and dynamic appearance of women in the Resistance occurred precisely in the bloodiest phase of the Occupation, when the resistance organizations adopted mobilizations and demonstrations, carried out exclusively by women, as a means of struggle. It was during this phase that women’s guerrilla platoons were formed and women took on “male” tasks.

The action of women on the war fronts was a phenomenon unprecedented for the Greek context and was diametrically opposed to the socially accepted female norm, which did not allow conscription, the use of weapons and involvement in combat.

For women, their participation in the struggle also implied their “personal” liberation and emancipation. Indicatively enough, the only women’s organization called “Liberated Youth”, within the framework of EAM asked “to be liberated from the triple slavery of conqueror, boss and husband”. National liberation was linked to personal and social liberation. The war facilitated the massive entrance of women into the public sphere for the first time because it blurred the boundaries between the public and the private, challenging the traditional family values of Greek society. However, their contribution will be counted by the standards of the period as auxiliary, while it was more than a necessary condition for the existence of the resistance movement. Their sacrifices were related to the services that they traditionally provided, which were socially undervalued, thus, their contribution was considered insignificant or was totally ignored.

Although the gender division was clearly reproduced in the resistance movement, the war gave women the opportunity to act as historical subjects and gain self-respect and self-confidence through their resistance activities. In the Resistance, the ideology of the patriarchal family was breached, the role of the family and the control of men over women were weakened, and women undertook traditionally male tasks; there was considerably more gender equality than before. Ultimately, the resistance movement proclaimed its support for women’s rights and empowered women to vote for the first time in Greek history in local elections, as well as in the general elections for its parliament, the National Council in Free Greece, and encouraged them to stand up for their rights and freedoms.

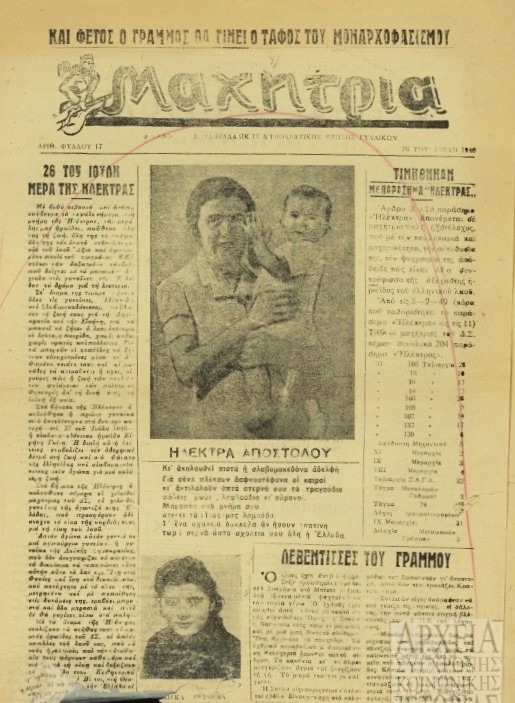

The advent of the civil conflict (1946-1949) marked a shift in the gendered division of military labour, as the female soldier of the earlier Resistance period gave way to the fully integrated female combatant. During the Greek Civil War, women constituted half of the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE), dominated by the Communist Party; thirty percent of its fighters and seventy percent of its personnel in support services were women. As polarization intensified, these women were either lauded as heroes within the rhetoric of partisan men and women or derided in the mainstream press, whose more extreme elements sought to dehumanize partisan women and portray them as national traitors and ruthless hyenas. The Right accused left-wing women of being dishonourable and called them prostitutes because, rather than focusing solely on their families, their main focus was on political issues. For the first time in Greek history, women were executed.

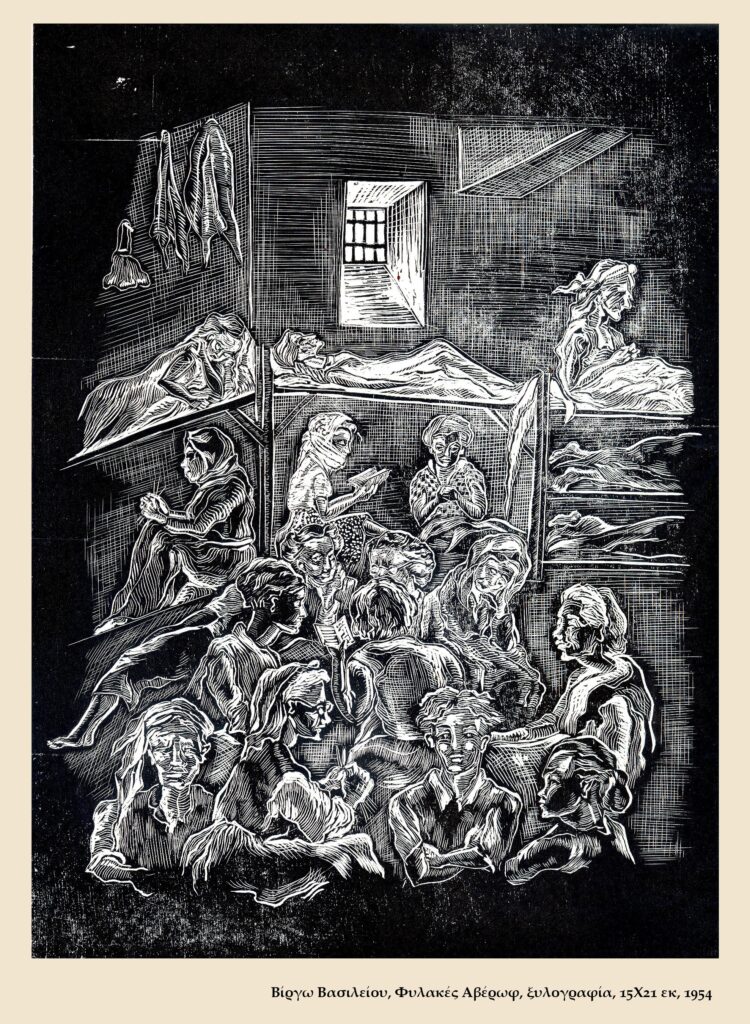

Women also began to be arrested, sentenced, and imprisoned or transported to island detention camps on the grounds that they were “dangerous for public order”. Not all of the women who were imprisoned or sent into exile had participated in the resistance movement or in the Civil War; there were also female relatives – mothers, grandmothers, aunts, daughters, and sisters – of men or women who were politically engaged on the Left, based on an alleged “collective family responsibility”, a sort of “political DNA”. At the end of the armed conflict, thousands of women, along with their children, were sent to the concentration camp established specifically for women on the island of Trikeri. Women were exiled first to Chios, then to Trikeri and Makronisos, sometimes moving to Ikaria and, later, to the island of Ai Stratis, where many were sent after the closure of the Trikeri camp in 1953. Many of these women would henceforth participate throughout their lives in social and political struggles through various groups, organisations and parties.

The women’s position in Greek society, where they were not allowed to publicly display their personal actions, the communist Left’s patriarchal character despite its progressive and revolutionary commitments, the post-war return of women to a domesticity beset with enormous political and economic hardships, the “male” devaluation of the women’s resistance activities and the focus on the armed resistance, and mainly the general political context in Greece until 1981, which excluded from the official narrative the communist-led Resistance, contributed decisively to the long-standing silence of the women’s role in Resistance.

Read:

- Janet Hart, New Voices in the Nation: Women and the Greek Resistance, 1941-1964, Cornel University Press, 1996.

- Margaret Poulos, Arms and the Woman. Just Warriors and Greek Feminist Identity, Columbia University Press, 2008.

- Tasoula Vervenioti, Η γυναίκα της Αντίστασης. Η είσοδος των γυναικών στην πολιτική [The Women of the Resistance. The Entrance of Women in Politics], Odysseus Press, 1994.

Watch:

- Ana Kesisogloy, Η γυναίκα στην Εθνική Αντίσταση και τον ΕΛΑΣ [Women in the National Resistance and ELAS], documentary, 1982, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mY95fGCGttQ&t=1s

- Alida Dimitriou, Πουλιά στο βάλτο [Birds in the Mire], documentary, 2008, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CXXM4ofT-JQ

- Alida Dimitriou, Η ζωή στους βράχους [Life on the Rocks], documentary, 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hKseJ8_ty_o

![Greek Girls, illegal proclamation, [1942-1943], ©ASKI](https://aski.gr/wire/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ASKI_Karra_05-1024x737.jpg)

![Poster of EPON [1943-1944], © ASKI](https://aski.gr/wire/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ASKI_Karra_06-671x1024.jpg)

![Greek women's resistance newspaper entitled "Storm" [Thyella], 1944, © ASKI](https://aski.gr/wire/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/ASKI_Karagiorgi_010-703x1024.jpg)