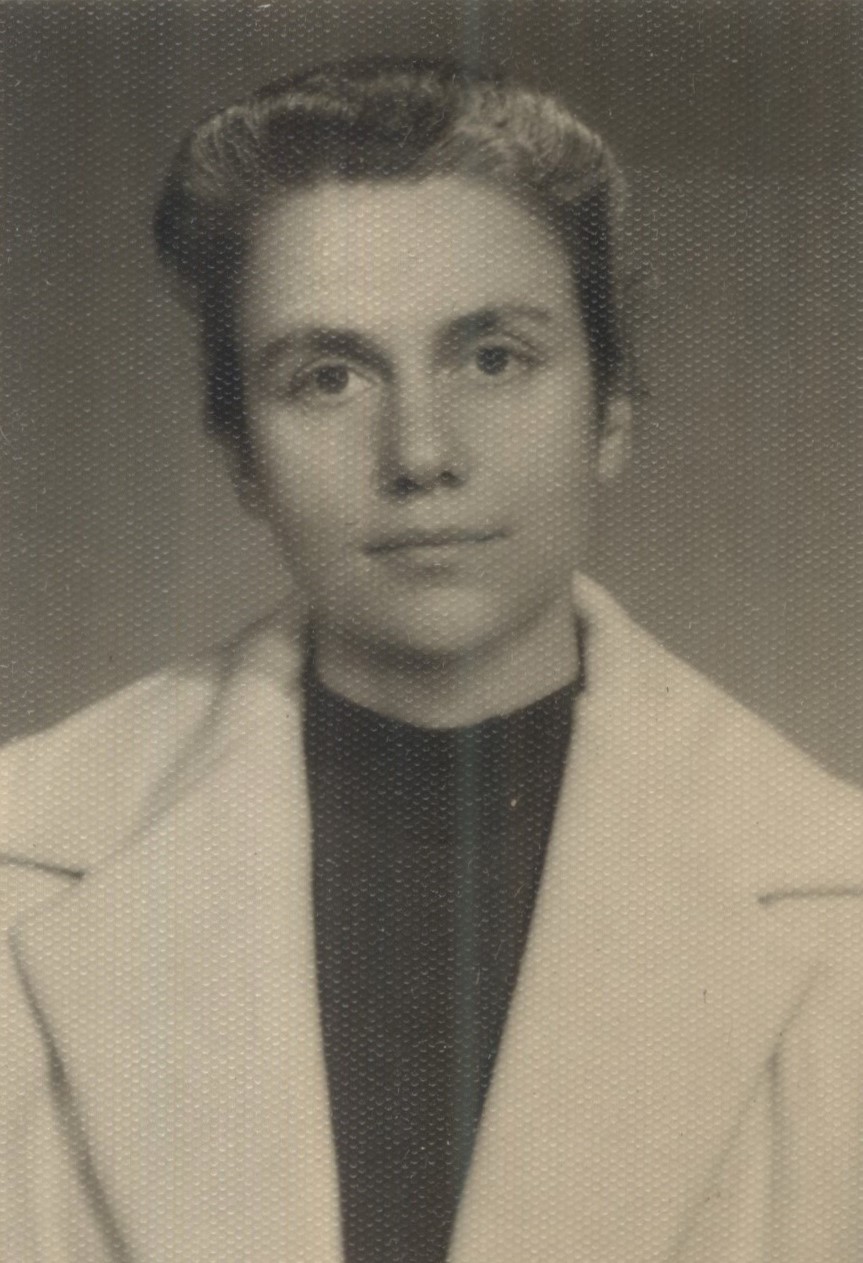

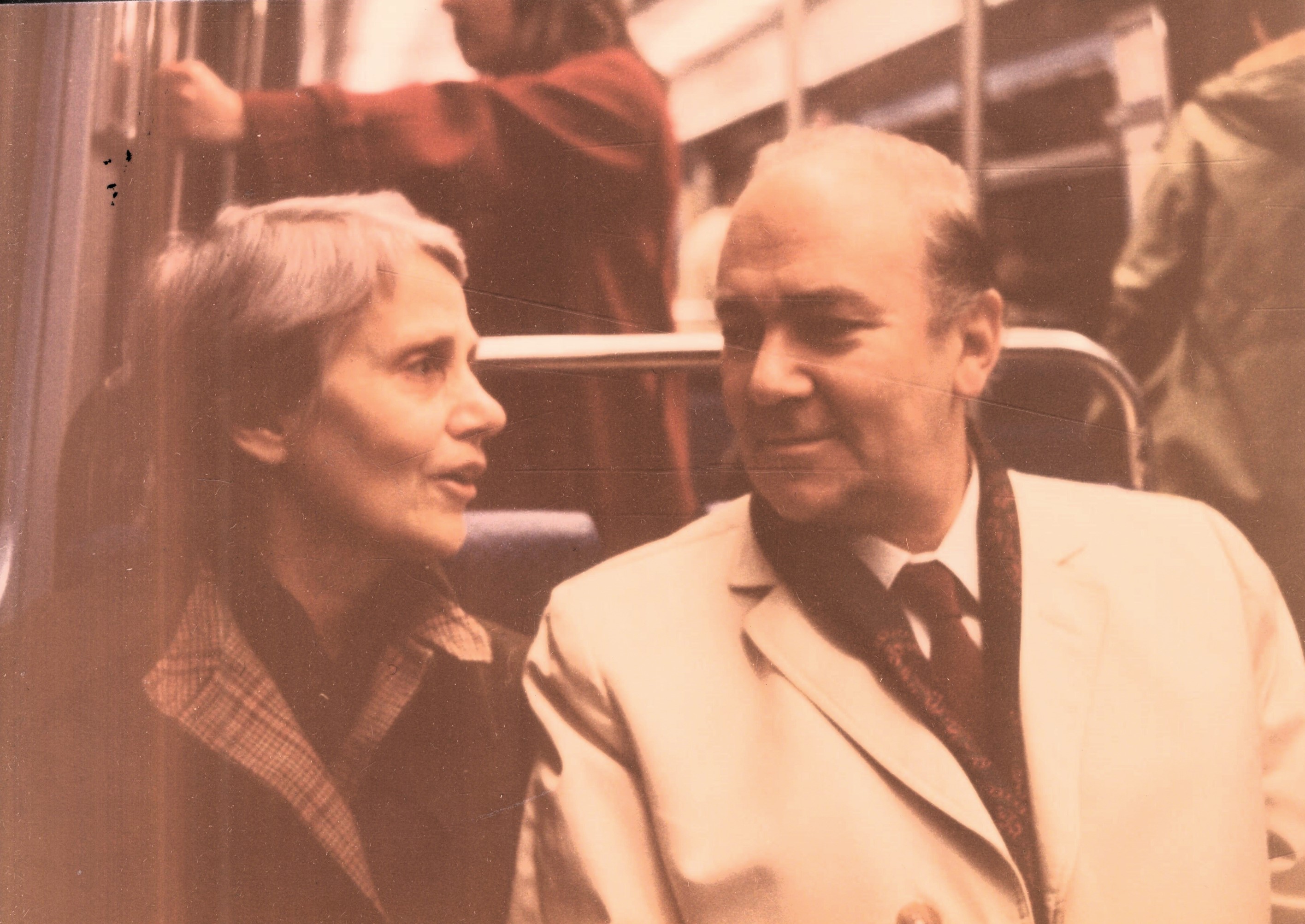

The difficult years in prison

Virgo Vasileiou remained in prison and then in exile from January 1948 to mid-1953. During her imprisonment, she contracted tuberculosis and spent some time in the prison infirmary. Her artistic inclination manifested itself in prison, as she systematically drew portraits of her fellow inmates. Indeed, in the absence of photographs, her sketches were often used in the official documents of the women prisoners. “In prison, I was deafening myself by drawing portrait sketches all the time. I don’t remember their number anymore. All the prisoners went through the makeshift photo studio. Artist and models, seated facing each other on stumps, transformed into stools. Not at all comfortable and terribly tiresome. At one time they began to send from the provinces to the prison administration applications for the release of prisoners, signed by their neighbours, and on the application, there had to be a photograph, with its authenticity guaranteed by Petrandi (the prison director). Strange as it may seem, the fact is that the portrait – sketch, took the place of the photographic portrait and was formalised with the prison seal and the signature of the person in charge. My fatigue from the intensity of the attention was great and I was missing the opportunity to stretch my legs a bit, strolling around the yard like the others. And then the models weren’t all that interesting. But I had to make sure that none were excluded.”

For a while, she was transferred to Patras Prison, where the conditions of detention were even worse. Her fragile health was shaken and she returned to Athens for medical treatment. The experience of incarceration defines her on many levels and the trauma is evident when she records her memories many years later.

“I went back around again to the nightmarish past times. Experiences like that scar you like burning seals on your body and soul. It’s hard to forget, to erase the past with a single finger. The world of prison and exile is an endless procession of women. Each with her own world, her own history, her own root. You wondered how most of them endured and dealt with the unbelievably cruel blows of their lives. Each prisoner carried her own drama and was difficult to express. In the visiting room, through the double screen, they each waited patiently for their turn to talk to their relative. There behind the double, thick as tulle wire, everyone was shouting, visitors and prisoners alike. You listened thus, unwillingly, to the requests, the pleadings, the news concerning the woman next to you. There were no secrets. Everything circulated, good news and bad news. We lived in a hellhole, a strange commune.”

![Vasos, Virgo and Kalliopi Vassiliou [1945;], Greek artist Virgo Vassiliou (1925 - 2001) participated in the National Resistance and she was imprisoned and exiled for her involvement in the movement. (ASKI, Virgo Vasiliou Archive)](https://aski.gr/wire/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ASKI_Vasiliou_01.jpg)