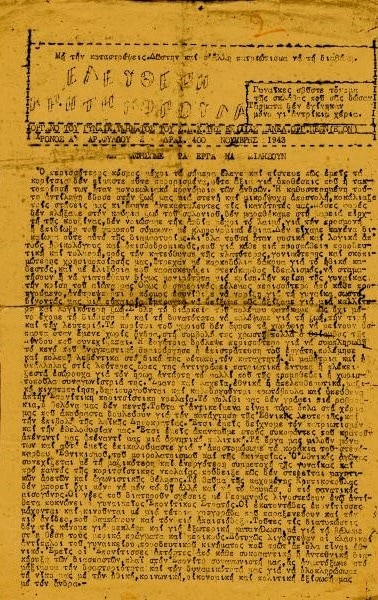

In 1943, while many guerrilla organizations had been formed in Crete, at the age of 15-16, as a student in the second grade, she joined the EPON. “Some [old] classmates talked to me, I was a very cowardly and weak child, they told me about the organization that the young people had formed and I was touched by this and I asked if I could help. I was always an ideologue.” In the first period, in Chania, she did nothing “militant”, as she says, she took care of food collection, the breadlines and assisting families who had lost their loved ones. “We did mainly companionship, hanging out, some small feasts and talking about the programs and tasks of the organization.” Then her activities expanded, the EPON entrusted her, together with other members, with the supervision of some villages (Akrotiri Chania and Riza White Mountains areas). There the young fellow collected supplies for the partisans, delivered messages, talked about the purpose of the organization and tried to convince the young people to integrate. “Now how persuasive we were then at that age of 18…” she would later ask herself.

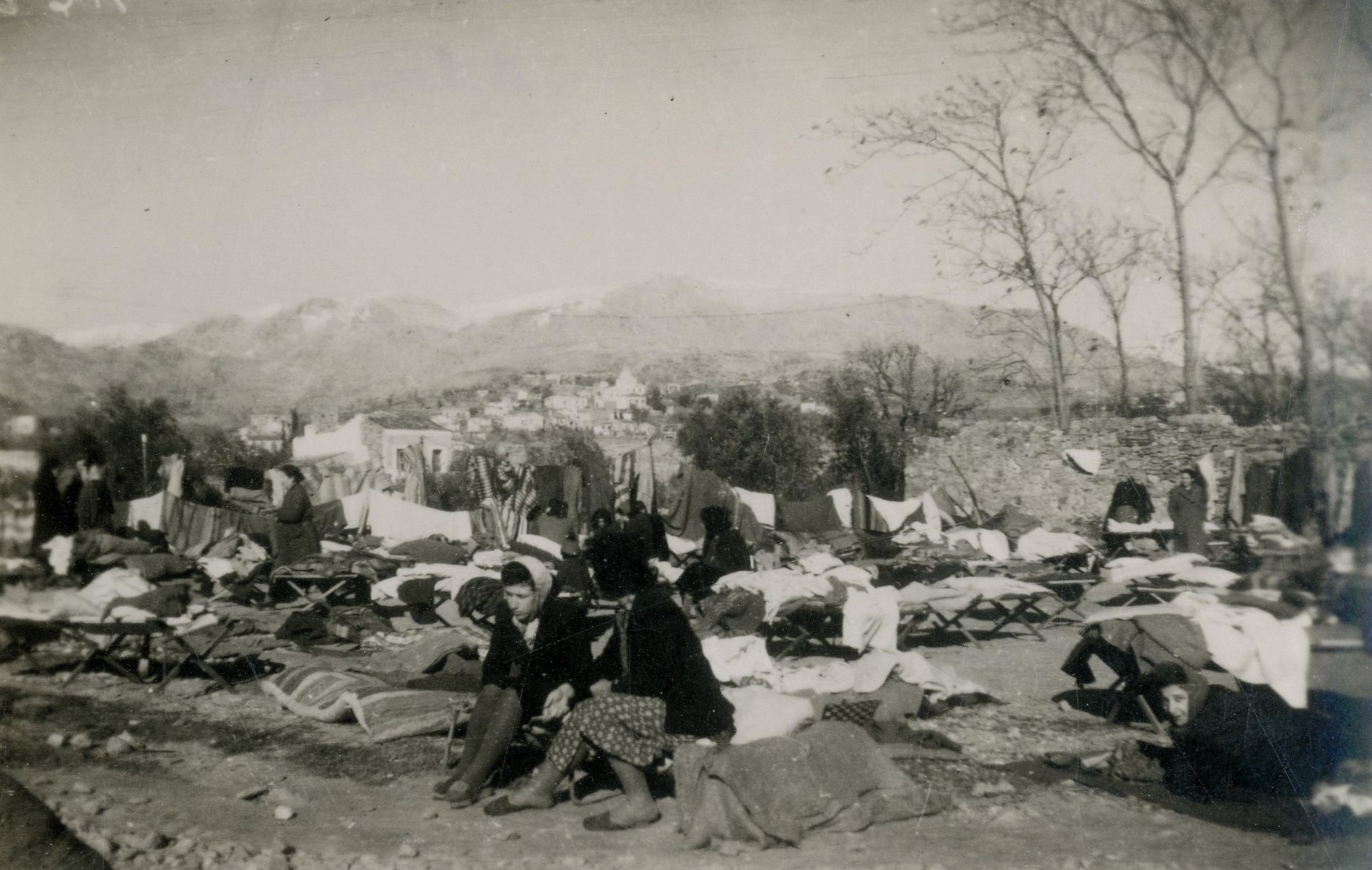

Although she had left home at a young age, “my mother actually lost me, but the climate was such that we had to leave to help” the resistance by going out at night and in secret, on EPON duties and in communication with the free areas. Eventually young Victoria was advanced into the mountains where the partisans were hiding. As she mentions “We were 3-4 young people, they were waiting for us, it was evening and we saw them high up on the cliffs, young men with guns in their hands and they called out to us. I will never forget that sight”. In the guerrilla groups, Victoria took on auxiliary work to support the armed sections (collecting food and medicine, cooking, cleaning, etc.). She recounts “…I woke up to pick out two sacks of legumes, where they were throwing upside down lentils, chickpeas in the wheat, whatever they were given in the villages… The next day a kettle was set up and food was made… the smoke should not appear and give us away…”.

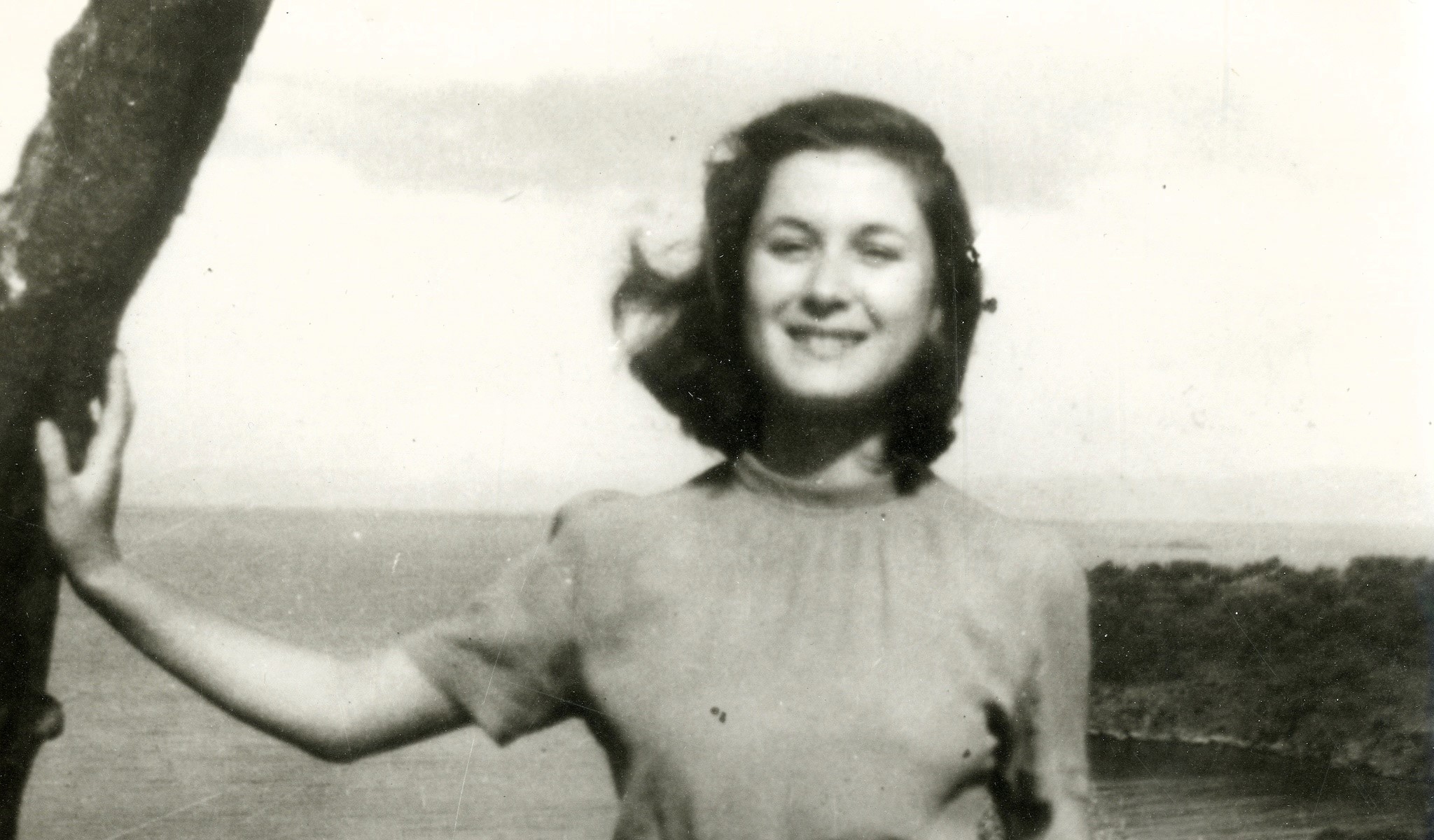

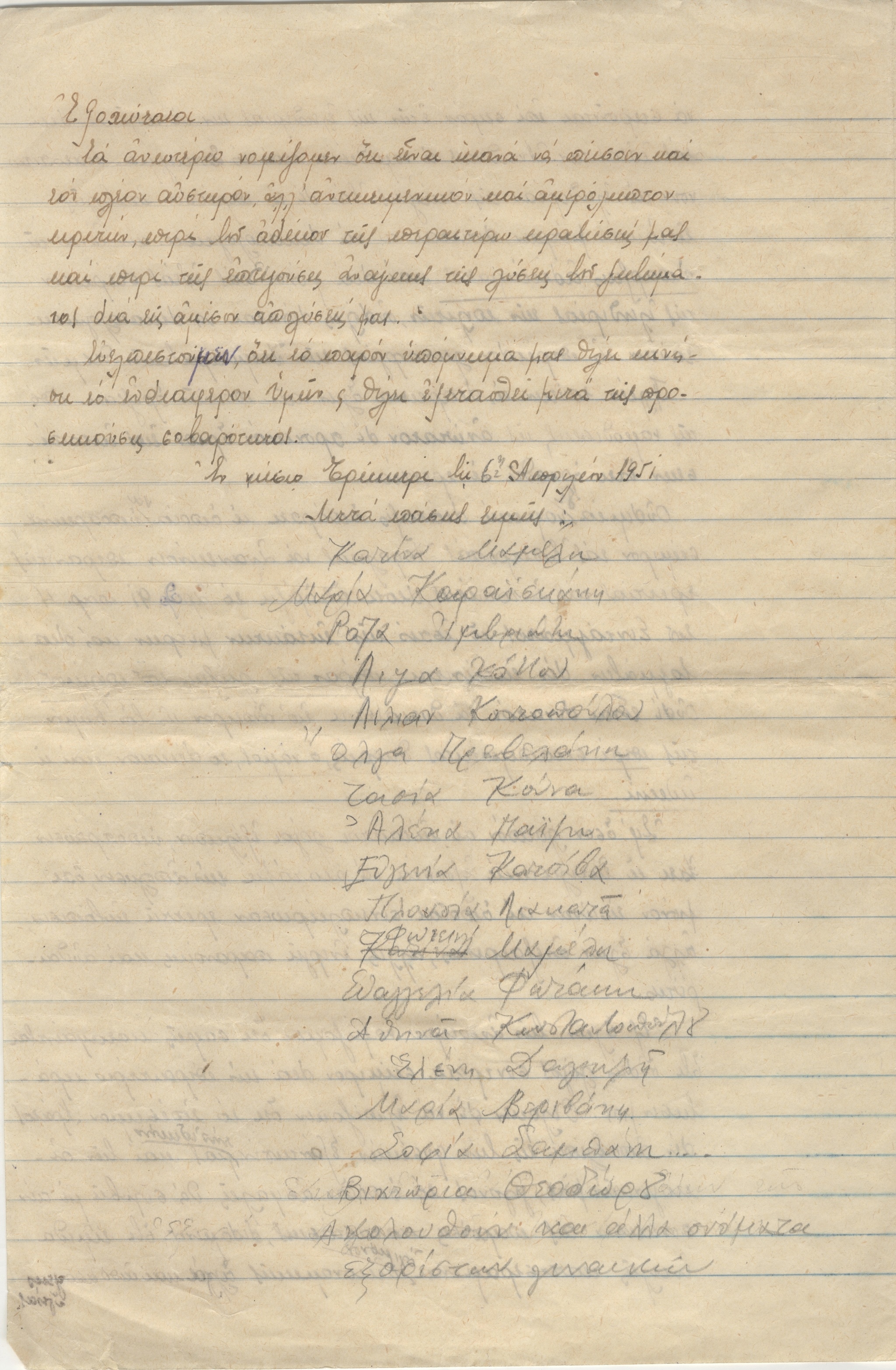

Low-key about her own actions, V.T. chose to talk about her experiences, indirectly, through literary writing. In her novel Gamilio doro [Wedding Gift], a story with many autobiographical influences, she reflected through her heroine: “If in the second great war we women took a rifle and climbed the mountain, it was more to gain independence from fathers and brothers. To defend our honor as we perceived it. […] Then in a way they recognized our rights. But as soon as the struggles were over, the liberation and social fights, they disarmed us.”

![Photograph of a gathering of young members of the greek resistance organisation EPON holding placards for membership in resistance organisations against the occupiers [1943-1944] (ASKI, Photographic Archive Anti)](https://aski.gr/wire/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ASKI_Theodorou_07.jpg)

![The Greek poet Victoria Theodorou (first right, standing) is photographed with other exiles on the island of Trikeri [summer 1949]. Behind them can be seen barbed wire fences that prevented access to the sea. (ASKI, Margaris Photographic Archive)](https://aski.gr/wire/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ASKI_Theodorou_14.jpg)

![The Greek poet and resistance fighter, Victoria Theodorou during the German Occupation [2000s]. (ASKI, Digital Archive of Alinda Demetriou)](https://aski.gr/wire/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ASKI_Theodorou_30.jpg)