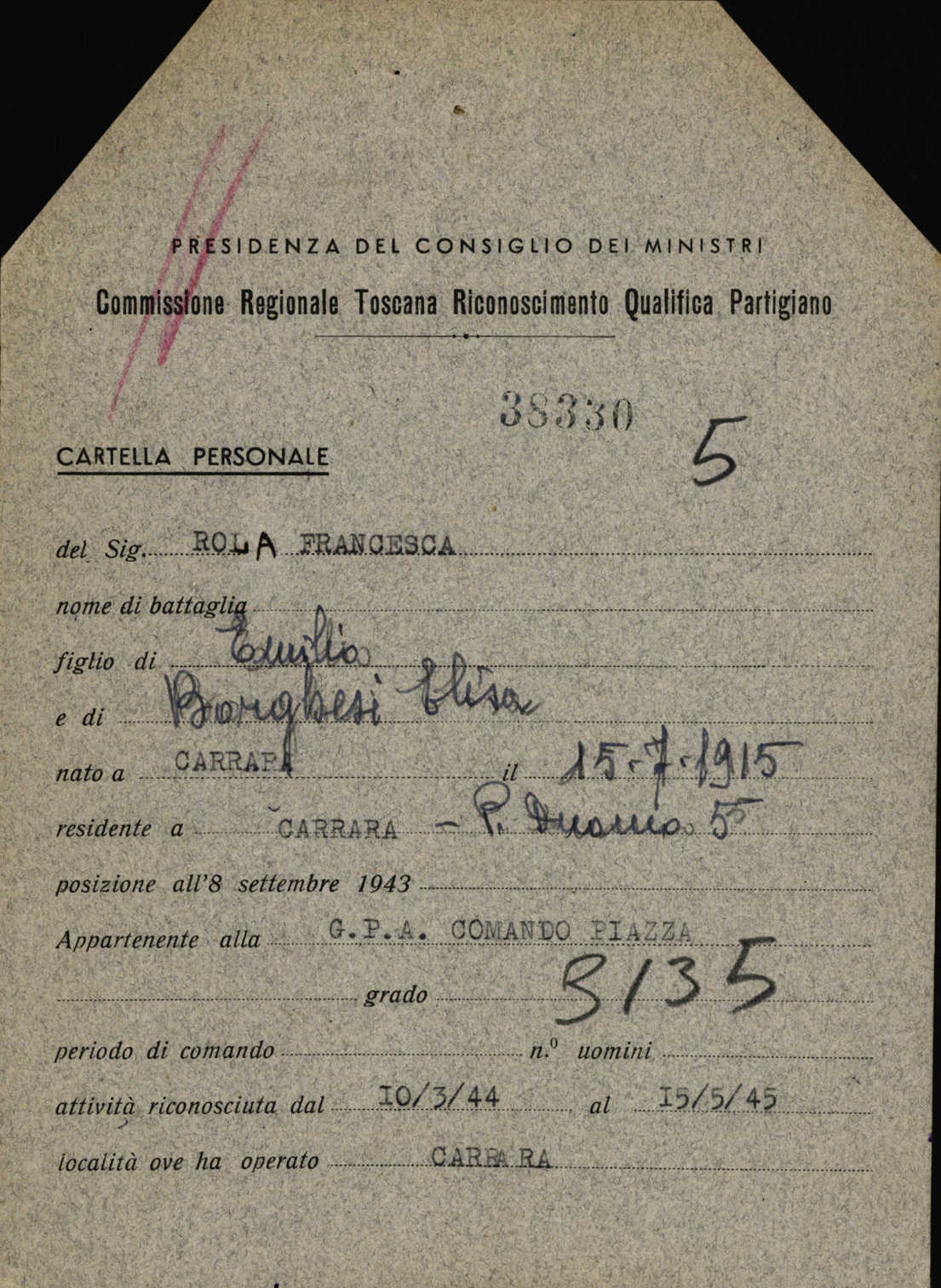

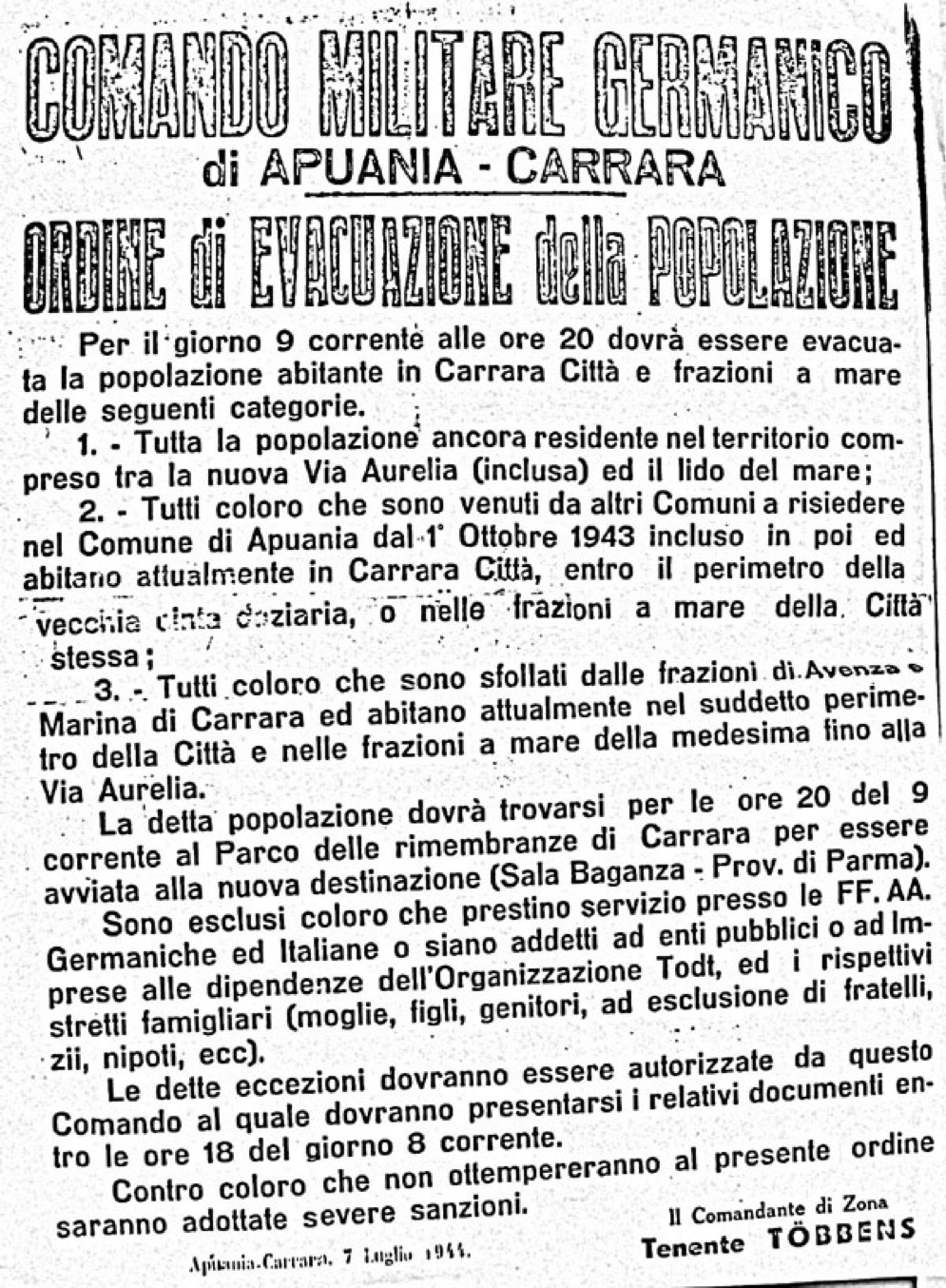

The territory of Carrara was located close to the Gothic Line [last Italian frontline], and due to its geographical conformation, its proximity to the Apennine chain, it represented a strategic point for the Nazi and Fascist forces. It was the ultimate, last defense to have access to the Po Valley and to northern Italy. It was therefore one of the “zones of operation” under the direct control of the Wehrmacht. From the fall of 1943, there was a succession of orders from the German command to evacuate the coast between Tuscany and Liguria. The goal was to have free space for action in case of a landing and a fight with the Anglo-Americans. This was all part of the strategy of clearing the territory, which was even more necessary at a time where the first partisan groups were beginning to form. Due to the evictions of the coastal cities, a situation occurred, in which it is estimated that around 200 thousand displaced people had found hospitality in Carrara. In early July 1944 the German command began to prepare for the retreat along the line on the Arno river and on July 7 the German commander Lieutenant Többens ordered the notice to be posted in the streets of the city mandating the total evacuation of the population for July 9, population destined to be displaced to Sala Baganza in the province of Parma. Only people in the service of the RSI [Social Italian republic, newborn fascist government], the Germans, and those working in the Todt Organization for the fortification of the Gothic Line were excluded from the measure. Immediately the local Liberation Committee and the Women’s Defense Groups [GDD] were mobilized, leaflets were printed and circulated, urging the population to disobey the ban. The phrase “do not leave the city” began to circulate, while the bishop sought evacuation as an option. On the day decided for evacuation everything stood still and nothing happened, making it obvious that it was difficult for the commands themselves to apply their directives. The people decided to remain in their homes, the population began to defend their roots and their territory, and it was the women, including Francesca Rolla, who was also active in the GDD, who promoted this popular mobilization.

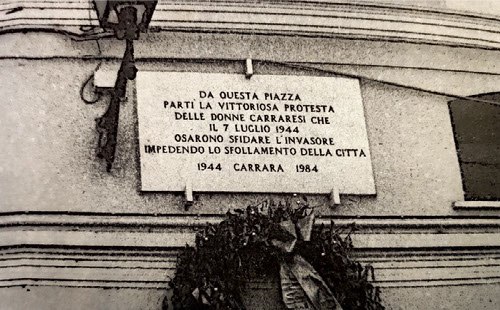

The uprising started on the morning of July 11 on Piazza delle Erbe, the site of the city ́s fruit and vegetable market with the slogans “We don’t want to evacuate” and “We won’t move from the city”. The women began to overturn baskets of fruit and vegetables and then marched through the city streets in a procession in the direction of the German command, while partisans concealed at a distance to be ready for action in case of a German reaction. This is how Rolla remembers: “On the morning of July 7, there were so many women, because we went to get them all; you go and get them all house by house, they came out, ‘Come out’, ‘no’, ‘come out’; if you don’t want to leave, if you don’t want to evacuate Carrara, to make everyone taken away, come out, come out, for God sake! […] We were all together, those who had more responsibility and those who had less responsibility, understood, however, that we were all a scrum, let’s say, practically we were all in the scrum. […] There were also Republican women and Christian Democrats, we were all together. The bravest ones that day would show up in front of the German command, or even in front of the tanks: me for example.I have a photograph that I can’t find – in front of a tank that Renata, poor woman, poor Renata, I can still hear her: ‘Oh Francé, come away they will shoot you!’ ‘And if they shoot me, after all I am just one, in case it is just me dying, come on girls, are you stupid? Do we have to show that we are afraid ? I’m not afraid, I stand here in the front: tell me they will try to shoot, try to shoot – and meanwhile I was looking at them, right? In the muzzle – let them try to shoot, to see if they are capable of shooting’. There was no moving in front of that tank, which was near there. Then we went to the little square, throwing everything out so that all women would have gone with us; we forced the schools to close, the stores, we shut down everything, everything”.