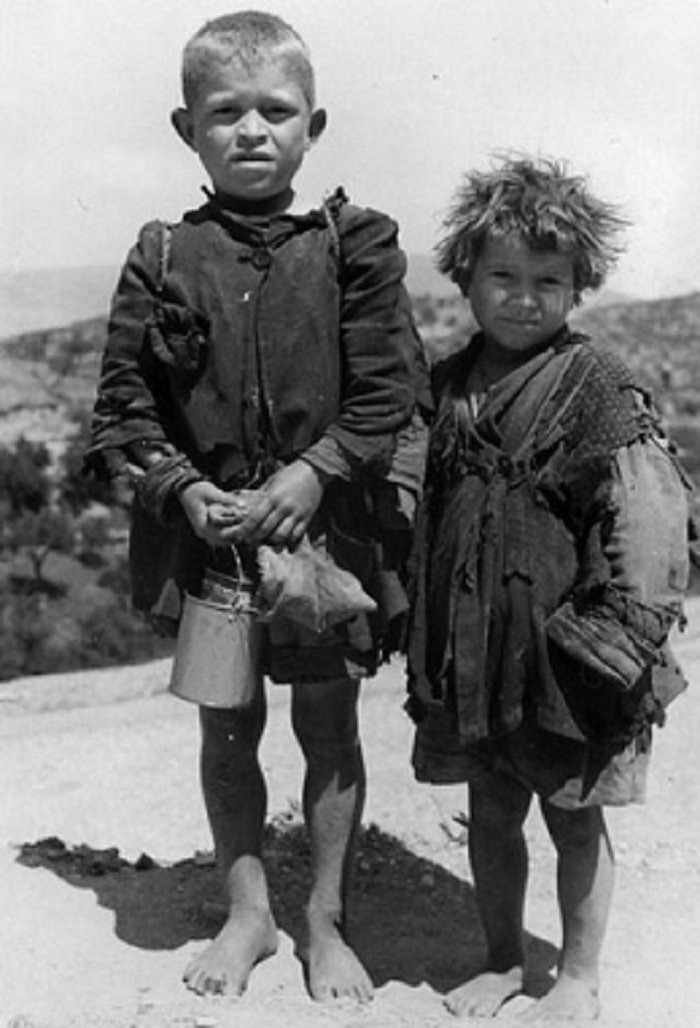

12 years as an outlaw

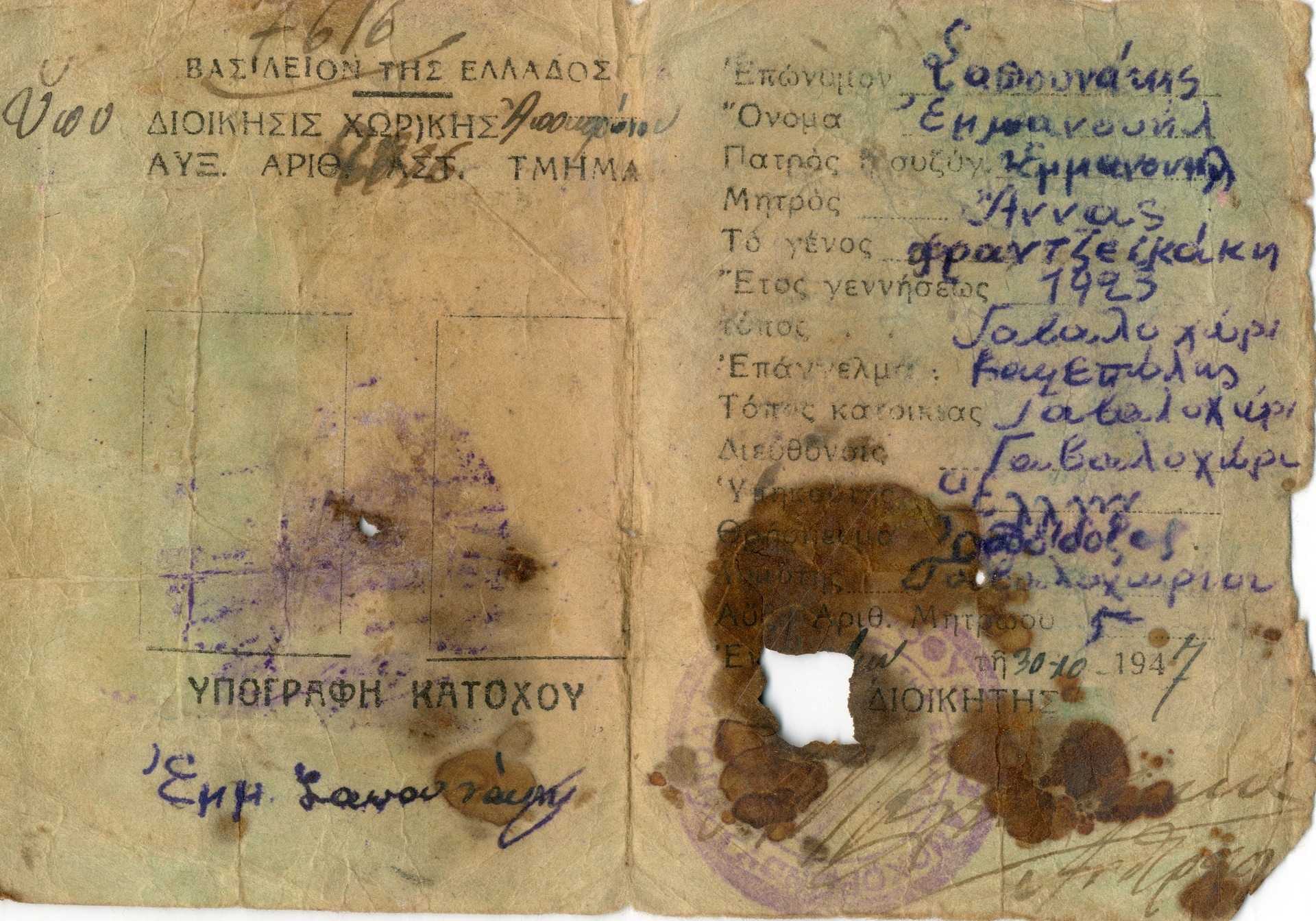

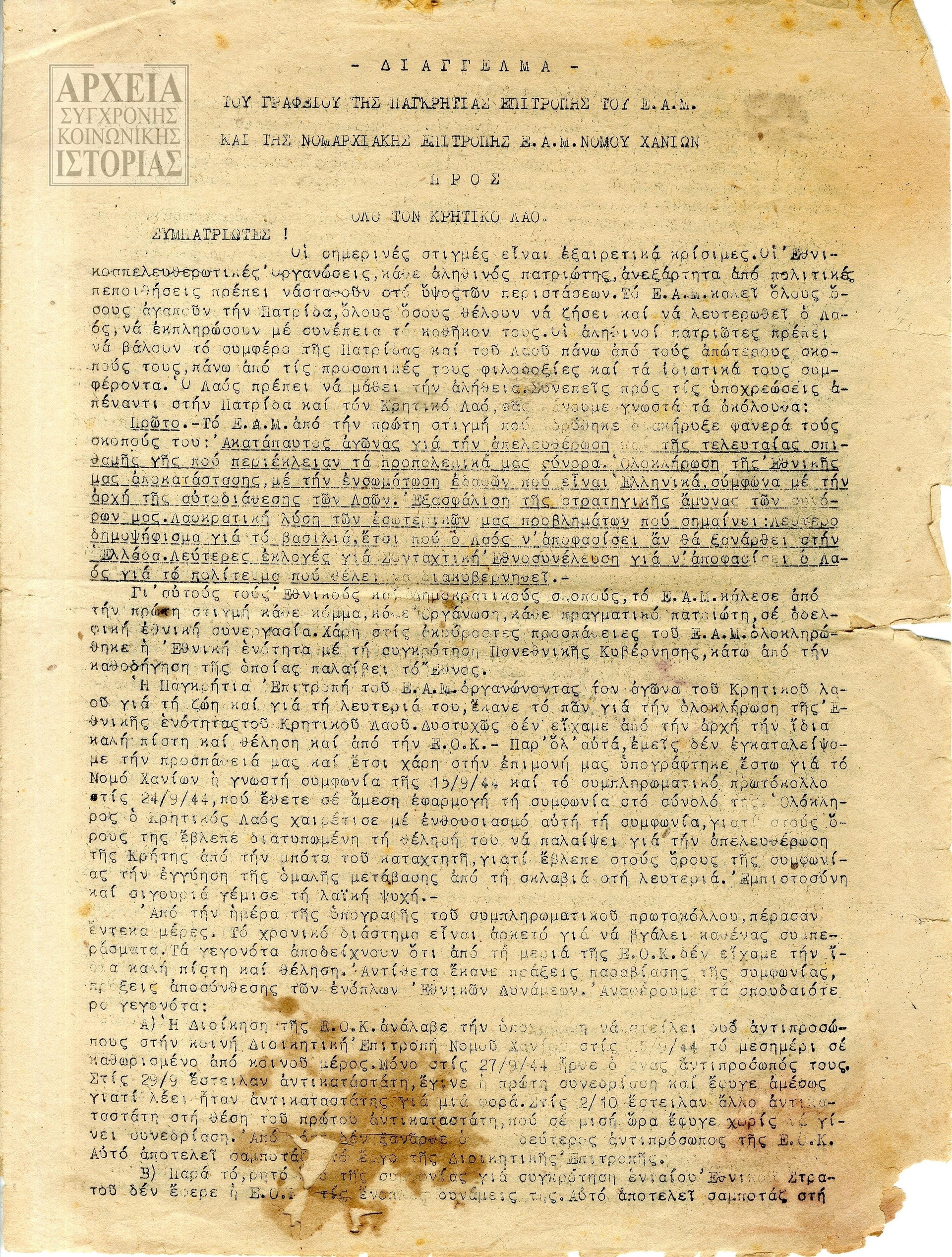

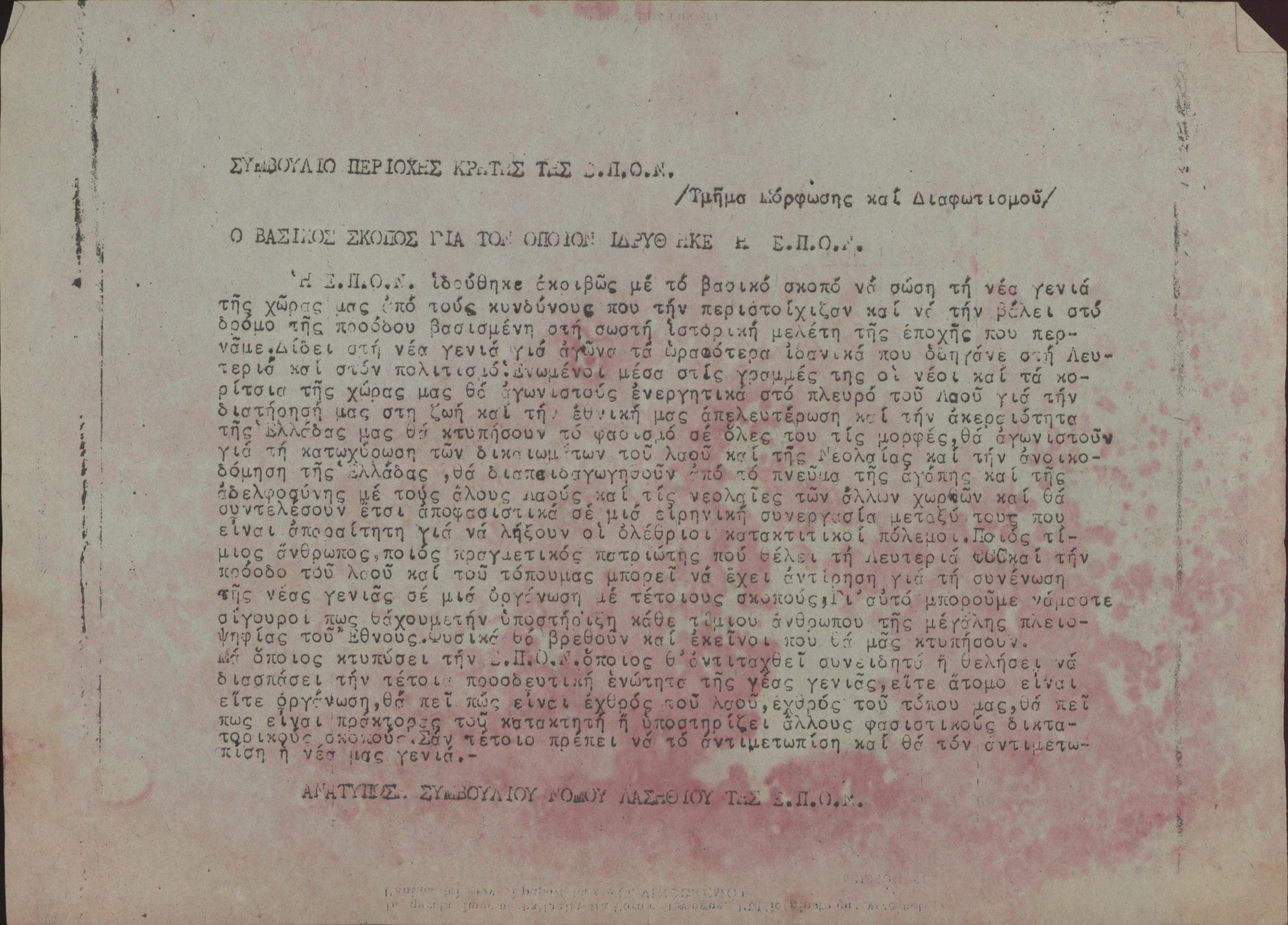

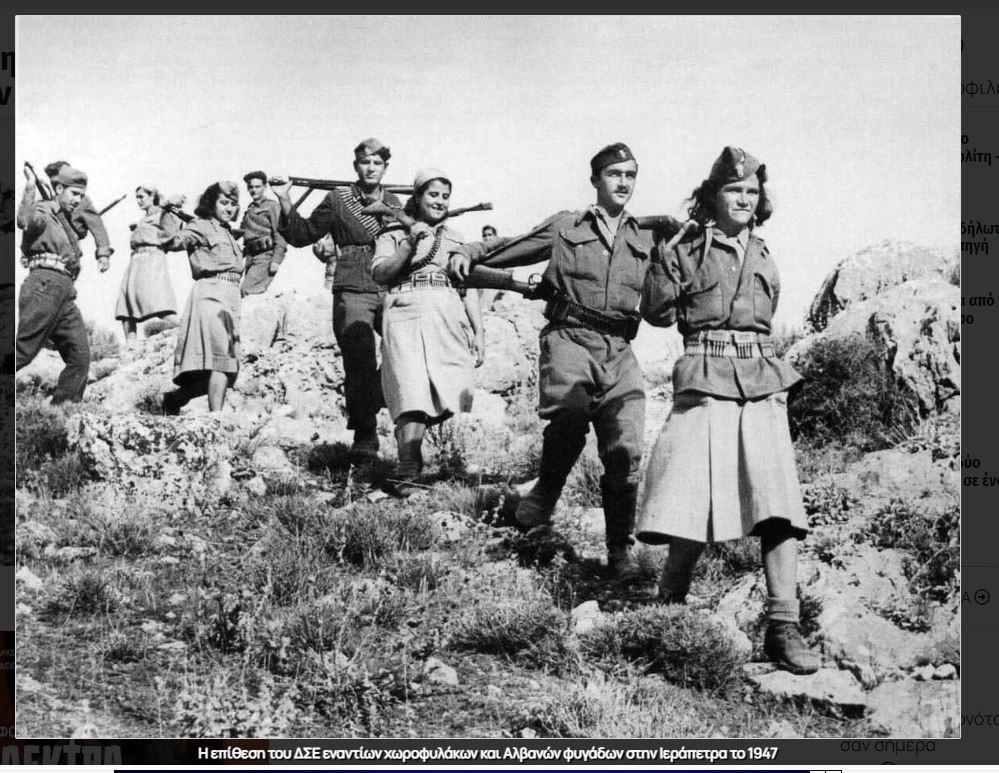

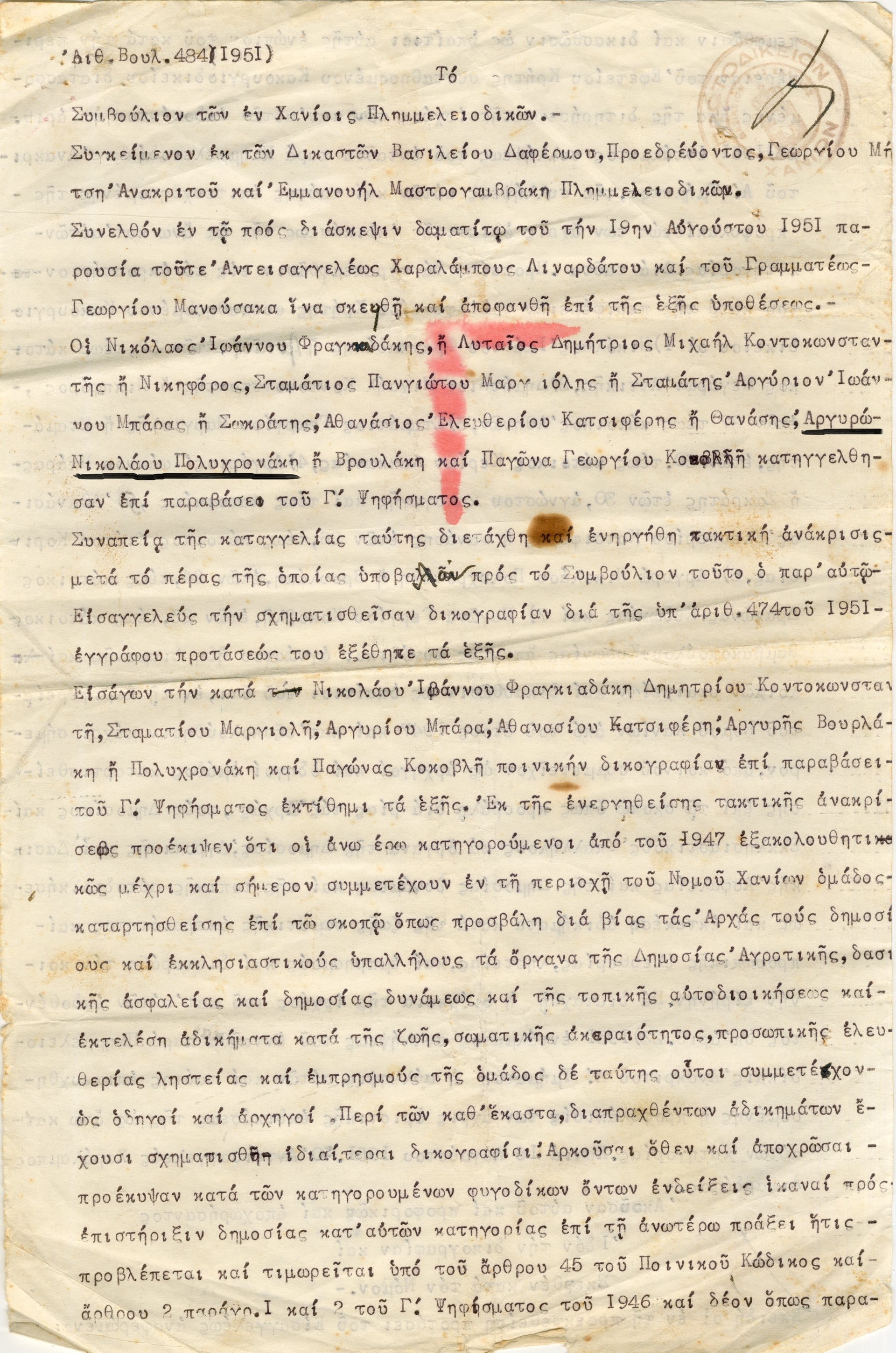

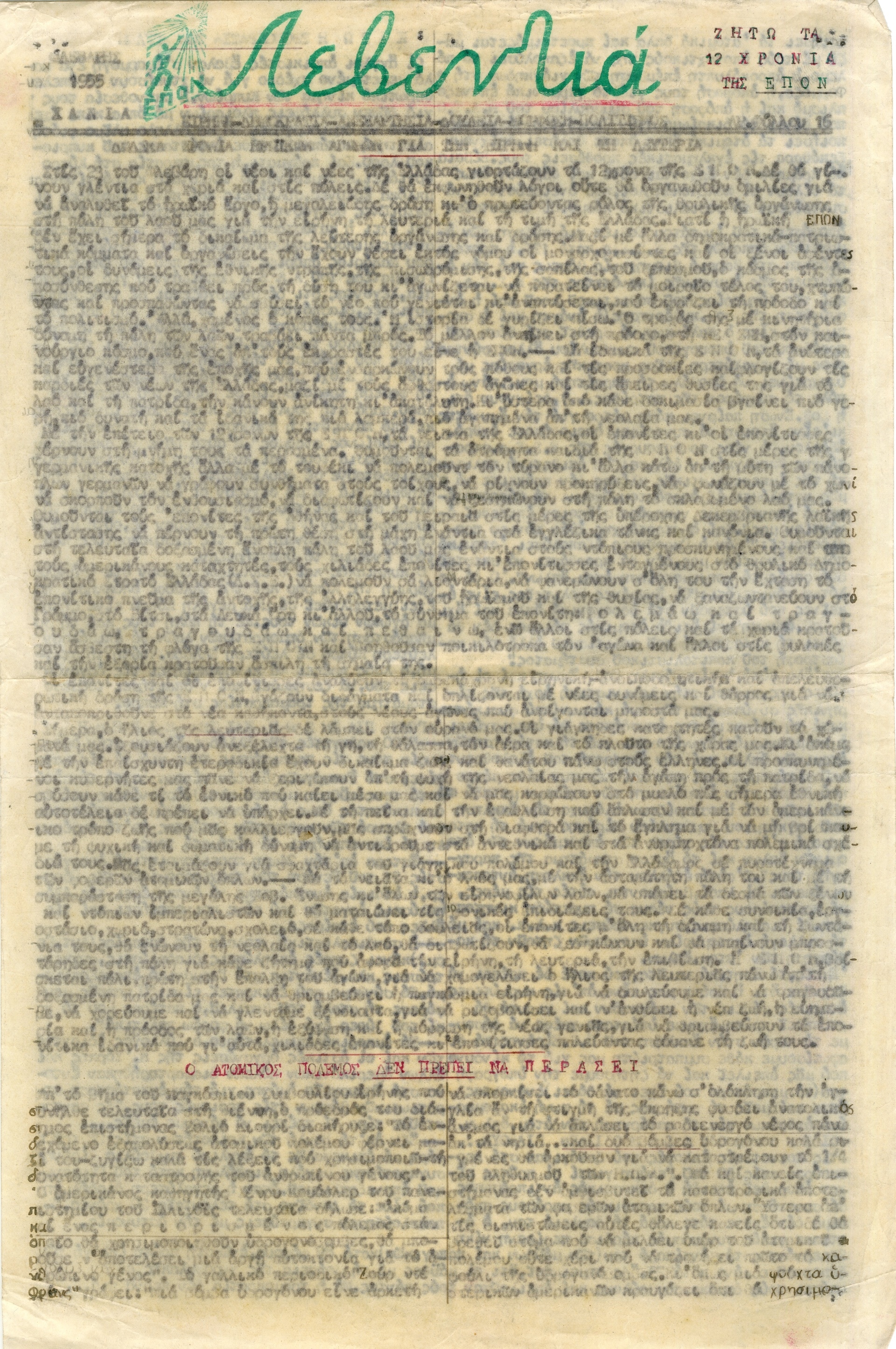

Towards the end of the Civil War, the guerrillas in the mountains of Crete were far fewer, and due to the endless persecution, the organization had shrunk or been disbanded. With the end of the war, Nikos Kokovlis and Argiro Polichronaki met again, and in 1950 they began their life and struggle together –they married in 1962 in the USSR– committed to continuing living illegally and hounded. Together with them were another 12 people, the ones that had not been arrested or killed, including the sister of Nikos, Pagona. They were all hunted, with a bounty of 250.000 each. From the mountainous caves that they hid in initially, they came down to the plains so that they can access the city of Chania more easily and resurrect illegal party organizations. The hardships were extreme, the illegality heavy, the chase of the terror, and the frequent increase of their bounties continued incessantly. Under these conditions, Argiro was in charge of the illegal EPON in Chania from 1951 and simultaneously worked in the secret printing mechanism.

Under this extreme secrecy, Argiro and her husband managed to evade arrest for 12 years, despite the state unleashing large operations to catch them alive or dead. Hiding in crypts built specifically as hideouts for many days, with the support of friends, they continued their work in the illegal organizations until 1958-1959 when they accepted the party directive for their disbandment. “The people helped us, there were those that were ideologically opposed, but did not give up even after being tortured” Argiro mentioned.

Cut off from her familial environment, Argiro distinctively remembers the random encounters with family members. Once, the house that they hid in at Chania was visited by her niece, the daughter of her sister without Argiro knowing, who introduced herself with the alias Athina, she did not reveal herself to her. The same had happened a while before with a cousin of hers, who was organized in EPON, who did not recognize her and ironically boasted about his cousin, not realizing he was speaking to her. He even wondered if she was alive as in her village they had held a memorial service for her. Argiro could not reveal herself, “and tell him it’s me, nor could ask for her parents, and what happened in the village during those turbulent years. These are the unwritten rules of being illegal. If you did not follow them, you were lost, together with those who helped you”, she recalls.

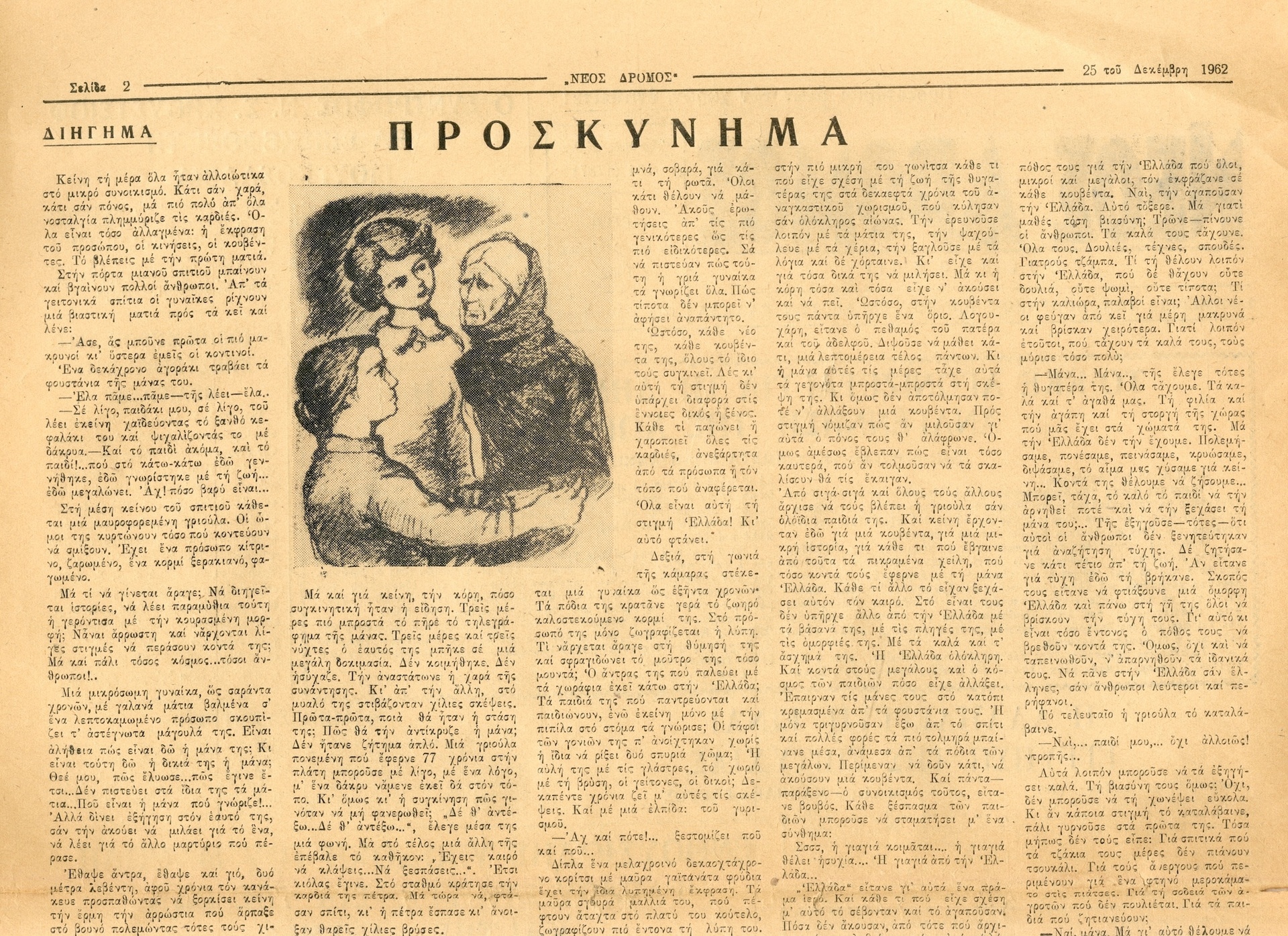

![Handwritten note with coded data, in the form of a pamphlet [written in very small letters on a small piece of paper] and sent to Nikos Kokovlis on the issues of the members of the illegal organization of Chania, Dec. 1950s-early 1960s. (ASKI, Archive of Nikos and Argiro Kokovli)](https://aski.gr/wire/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/ASKI_Kokovli_15.jpg)