Alina was born on 12 January 1952 in Gdańsk to Tadeusz and Helena Pabijan. She was the eldest of four children. Her father, who hailed from a small village in southern Poland, arrived in Gdańsk shortly after the end of the Second World War. He wanted to start a new, independent life in the port city, which offered the prospect of working in a shipyard. Her father’s experiences later turned out to be one of the fundamental sources of Alina’s opposition creed.

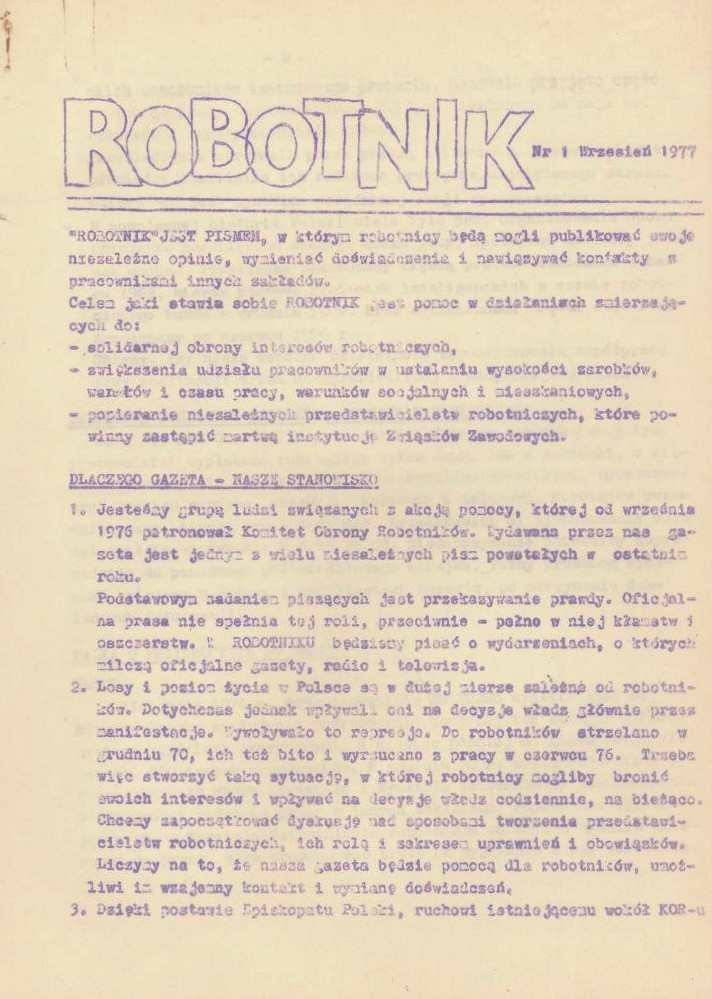

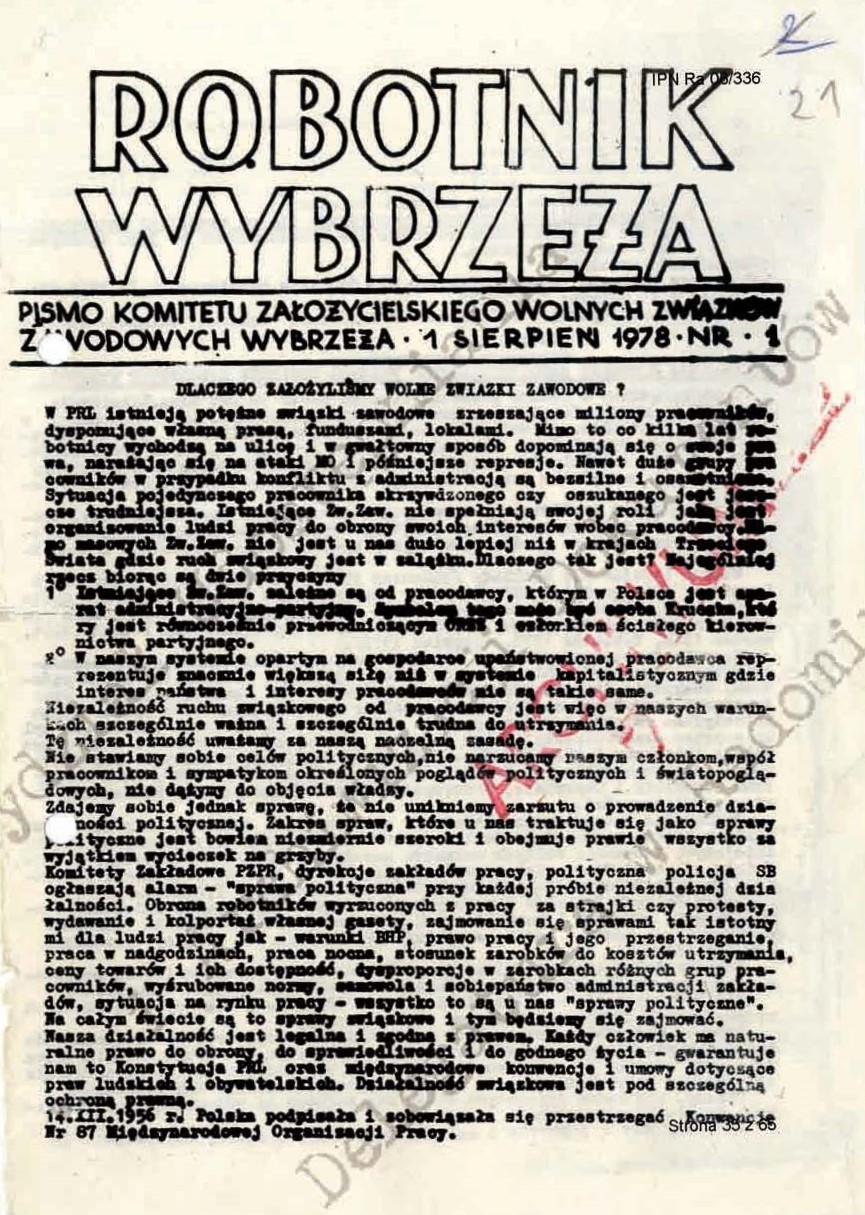

Long before commencing her union activity, Pienkowska made quite an impression on her Gdańsk high school peers. A student who had until that time been considered quiet and shy, in December 1965, she openly criticised the propaganda message conveyed by the Trybuna Ludu daily regarding the approach of the Catholic Church towards Polish-German relations following World War II. This was sufficient to prove Alina’s political maturity and the rising criticism with which she viewed the world. Pienkowska herself, however, pointed out that the key moment in which she “became convinced of the hypocrisy of the system” were the December 1970 strikes triggered by increases in the prices of meat and other foodstuffs planned by the government.[1] Even though Alina did not participate in the December 1970 strikes, she had a chance to listen to her father reporting on them in their kitchen, behind the half-closed door. Comparing his words to the official press narrative, Alina was able to learn what government propaganda is in practice, and how censorship works.

[1] Back in those days, prices were officially fixed and salaries were relatively low. In 1970 the average pay amounted to PLN 2,235 per month. To put things into perspective, the monthly pay was sufficient for a customer to purchase 27 so-called “grocery carts” (1 loaf of bread, 1 kg of apples, 2 sticks of butter, 1 kg of pork meat), while in 2015 you could buy approximately 163 (!) such carts. Najnowsza historia Polaków: oblicza PRL, nr 13, 22.01.2008, s.15.