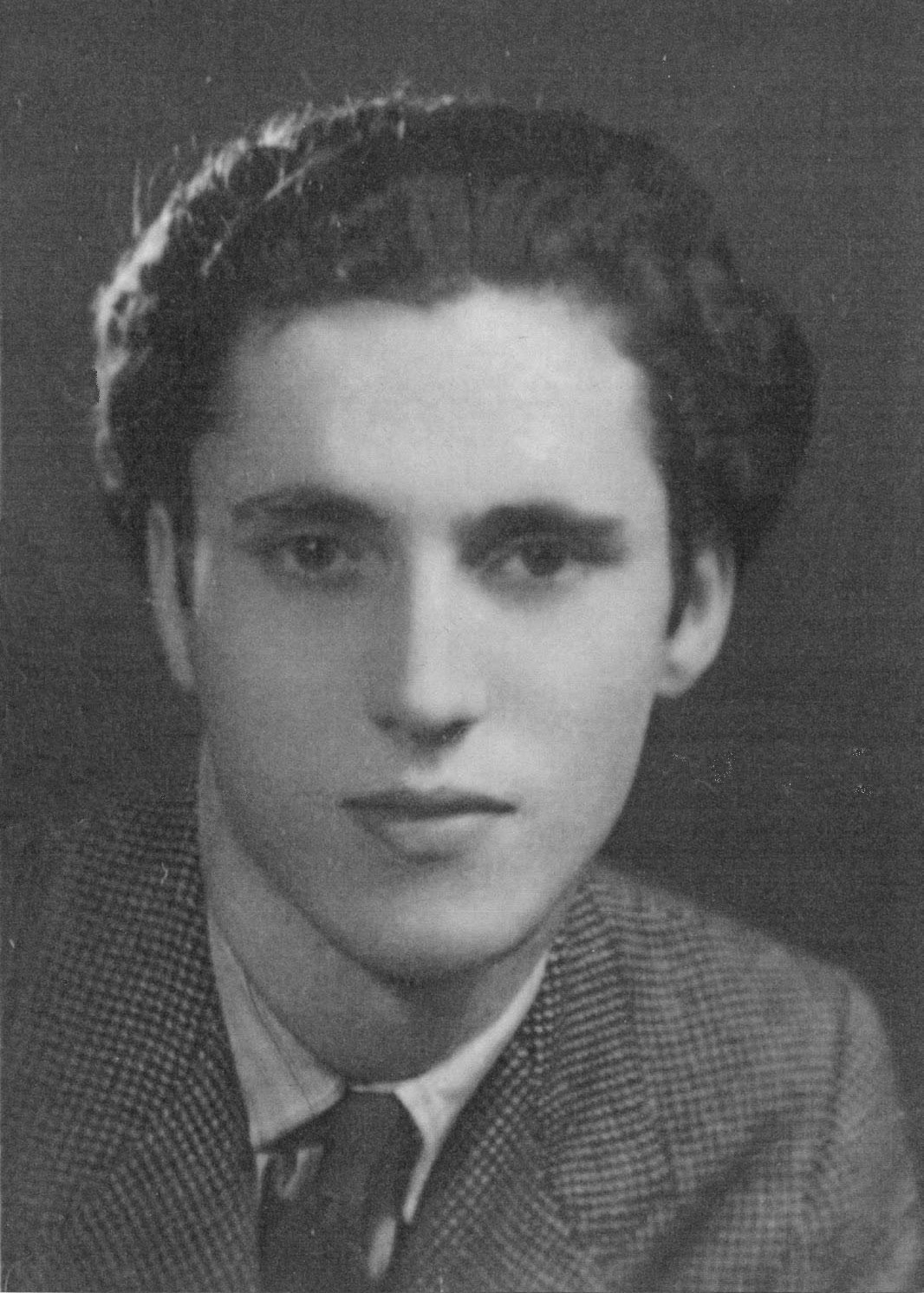

On March 10, 1944, Lucia, Mario Fiorentini, Rosario Bentivegna, and Franco Ferri attacked the procession of the Honor and Combat groups parading down Tomacelli Street with machine gun fire and hand grenades[21].

Lucia participated in the preparation of the Via Rasella attack, which, in the intentions of the Commands, was supposed to be an unprecedented strike, but did not take part directly because she was ill[22]. After this episode (March 23, 1944) and the following reprisal of the Fosse Ardeatine (March 24, 1944), Gappist Guglielmo Blasi, captured by the Police following an armed robbery, yielded to Pietro Koch’s offers of money and put himself at his service. The pact stipulated that Blasi would accompany the Fascists to agreed appointments and would receive a substantial sum for each arrest[23].

The first to fall under the blows of the delusions were Carlo Salinari, Franco Ferri, Franco Calamandrei and others. Calamandrei managed to escape through the window of the cabinet of the Jaccarino boarding house, used as a prison, and gave the alarm to his comrades and lived in hiding until the liberation of Rome. A few days later, Capponi and Bentivegna also risked capture, as did Fiorentini and Ottobrini. Blasi gave an accurate description of the organization and the objectives it had planned, and Its main components were put out of action: the police now knew how the organization worked, who the leaders were, where the depots were, and what the new objectives would be. The Gappists were sent to the main consular routes with orders to attack the retreating German army to the north. The purpose of this different deployment was to form and lead new partisan formations to support the advance of the Allies-landed at Anzio on January 22 – in the direction of Rome[24].

In reality, operations on the front stalled and did not spring the expected results: the initial optimism soon turned into concern, especially in the face of the crackdown the Germans gave once they saw the Allies’ difficulties in moving quickly toward the capital. The most exposed partisans thus found themselves in grave danger: wanted but without safe lodgings[25].

Lucia Ottobrini and Mario Fiorentini, operated for a month in the Quadraro and Quarticciolo areas, then they were moved to Via Tiburtina, in Tivoli area: here the organization was weak and the two were forced to take shelter in improvised places such as caves or cottages abandoned by peasants after the bombings, with scarce food supplies and equipped with light armament not adequate to attack entire columns of German soldiers: “For seven days we ate only fresh cherries and fava beans… then only chicory. I remember Mario’s face one day when he boiled chicory and ate it like that, even without salt, and he repressed his disgust and said to me: “Eat it’s good, you know?”… It was festive when the peasants gave us some potatoes and flour”[26].

From Tivoli, Lucia often walked along the Via Empolitana to Rome to maintain contact with the Regional Command, or to transport weapons, often at the risk of being strafed by Allied planes. She often had to take cover among the natural ruts in the ground to escape the bombing: “Even today during May evenings, when the sky is clear, I seem to hear the roar of the bombers,” she recalled[27]. One day during one of those missions Lucia passed a column of Germans singing from a distance: “Once I burst into tears when I heard very young soldiers singing a nostalgic ‘Let’s go home, where we’ll be all right’ in their language, which I spoke and understood. It was a hymn I had heard sung in Alsace”[28]. That song in German suddenly awakened her nostalgia for France, where she had left her memories as a child and teenager. After the bombing of Tivoli (May 26, 1944), she was sent to direct a partisan nucleus charged with preserving a hydroelectric power plant from German attacks, blowing up a military truck, with the rank of captain[29].

[21]Mario Fiorentini, Sette mesi di guerriglia urbana. La Resistenza dei Gap a Roma, a cura di Massimo Sestili, Odradek, Roma 2015, pp. 104-105.

[22]Mario Fiorentini, Sette mesi di guerriglia urbana. La Resistenza dei Gap a Roma, a cura di Massimo Sestili, Odradek, Roma 2015, p. 92.

[23] Massimiliano Griner, La “Banda Koch”. Il Reparto speciale di polizia 1943-1944, Bollati Boringhieri, Torino 2000, pp. 151-159

[24] Massimiliano Griner, La “Banda Koch”. Il Reparto speciale di polizia 1943-1944, Bollati Boringhieri, Torino 2000, pp. 159-161.

[25]Gabriele Ranzato, La liberazione di Roma. Alleati e Resistenza, Laterza, Roma 2019, pp- 208-228.

[26] Adris Tagliabracci, Le quattro ragazze dei Gap. Lucia Ottobrini, in «Il Contemporaneo», VII, 1964, 79, p. 56. Si veda anche https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mxox3cTSobE&list=PLXeCkZwzzuadBa1ZBJYa4zrgnNvuGF20Q&index=28

[27] FCesare De Simone, Roma città prigioniera, i 271 giorni dell’occupazione nazista (8 settembre-giugno 1944), Mursia, Milano 1994, p. 256.

[28] Fabio Grimaldi, Luca Soda, Stelvio Garasi, Partigiani a Roma, Manifestolibri, Roma 1996, p. 42.

[29]Alessandro Portelli, L’ordine è già stato eseguito, Roma, le Fosse Ardeatine, la memoria, Donzelli, Roma 2005, p. 160.