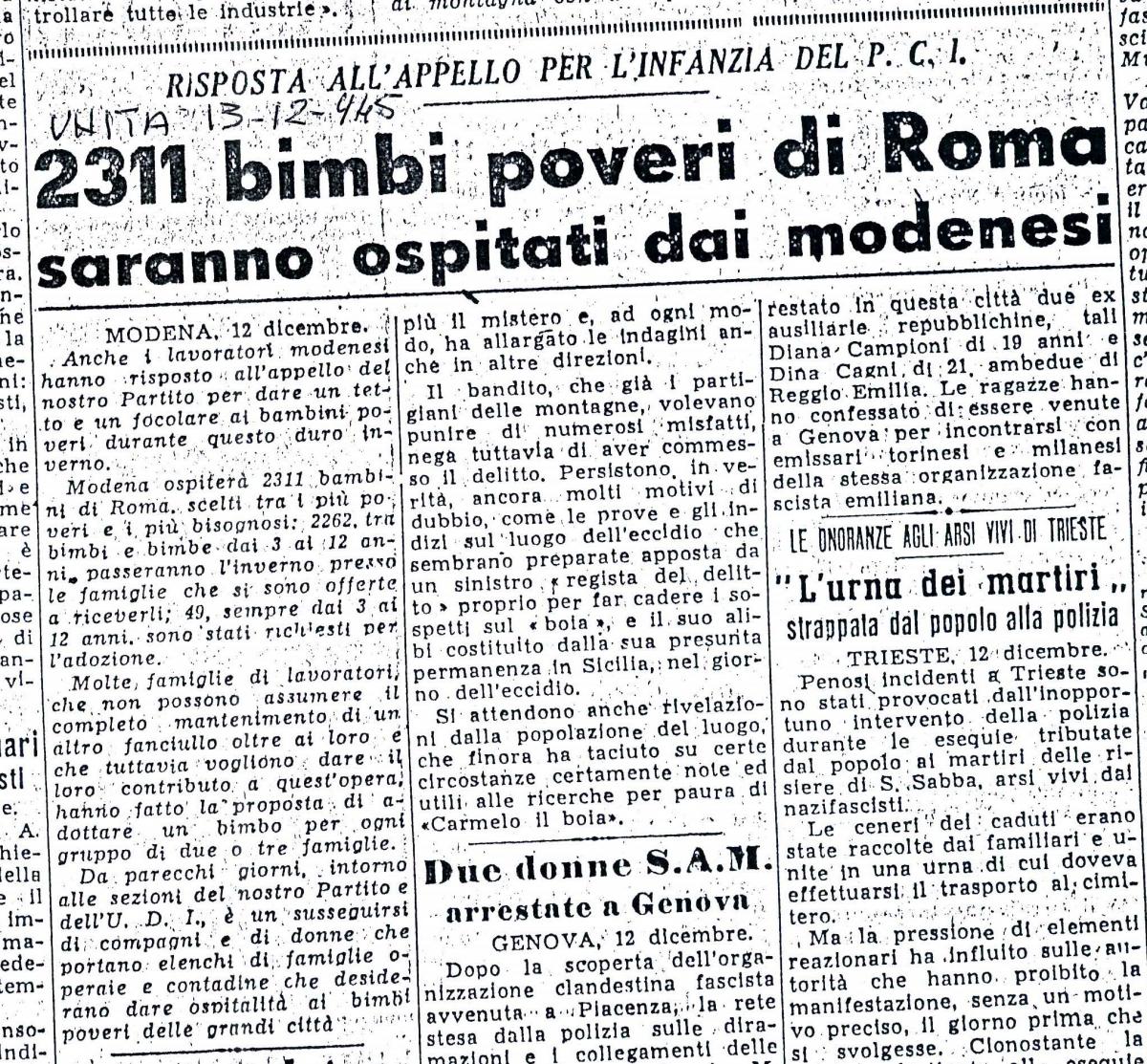

After the war she immediately resumed political activity for the PCI. One of the first initiatives she was involved in was what will remain known as the “trains of happiness” (1945-1947). Thanks to contacts cultivated with the federations of Modena and Reggio Emilia, she convinced her Emilian party comrades to house poor children from Milan with peasant families, to enable them to face the winter with sufficient food and lodging[37].

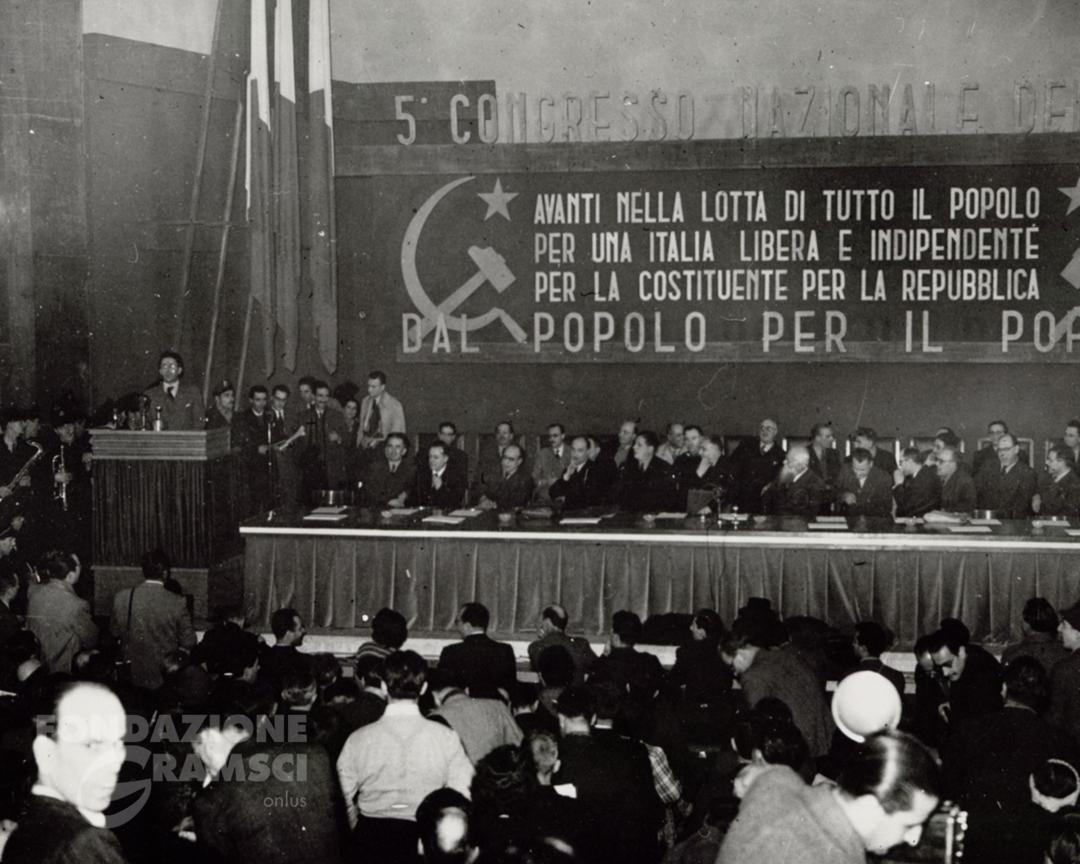

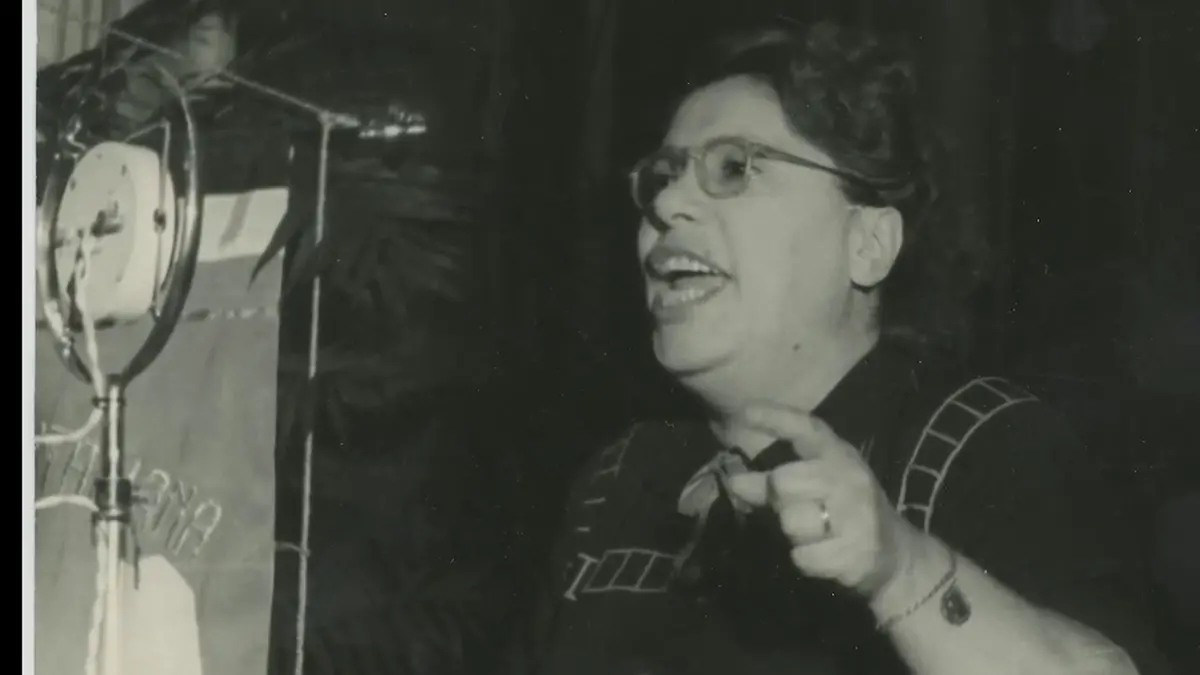

At the end of the PCI’s Fifth Congress (December 1945), she was elected into the Central Committee, into the Executive and designated as a member of the Agitation and Propaganda Commission[38]. Her most prestigious political assignment was her appointment to the National Consultation, a body that was to give opinions on legislative measures, such as the first electoral law in democratic Italy[39].

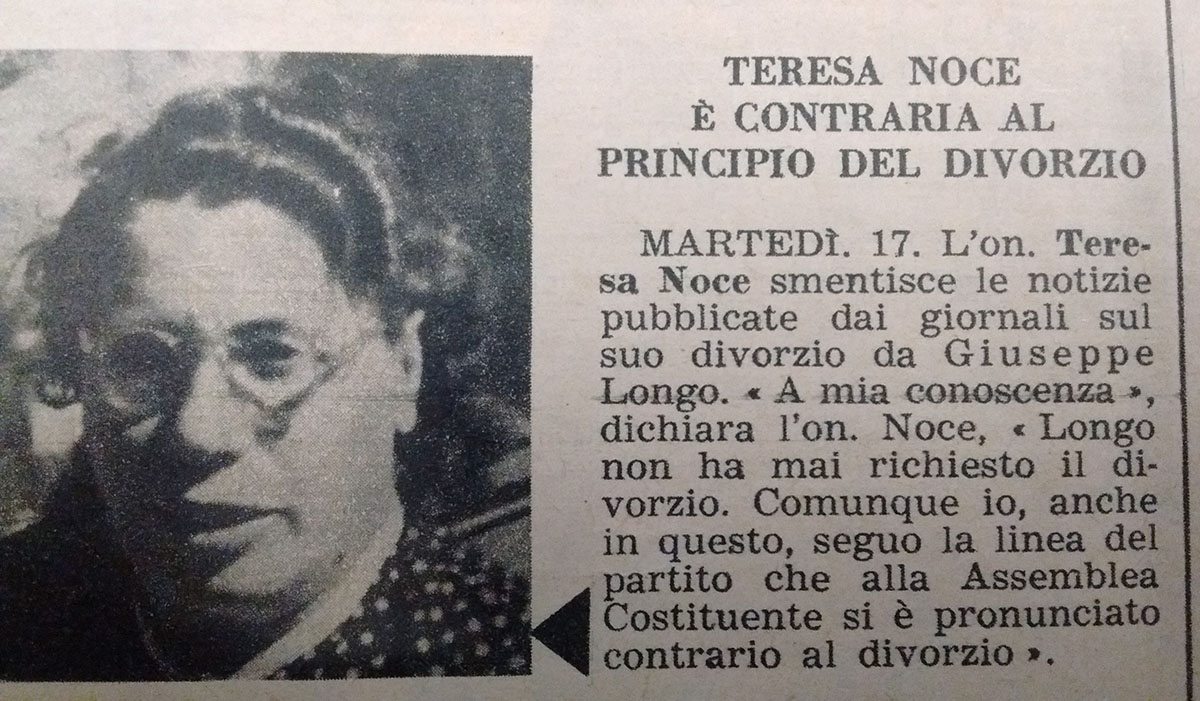

In the elections for the Constituent Assembly (1946), she accepted candidacy on the condition that she could choose her own constituency: the region Emilia, achieving great success that led her to become a “constituent mother”[40]. She then insisted on being included in the Commission of 75, which had the task of drafting the Constitutional Charter, where she focused mainly on the provision of family assistance that she discussed with Christian Democrat Maria Federici and Socialist Lina Merlin[41].

With her usual energy, she engaged in the first electoral campaign (1948) – which was characterized by an opposition between the DC and PCI – and helped in making the alliance between the PCI and PSI win in her constituencies (Emilia and the province of Brescia), despite a defeat at the national level[42]. After a long debate and a laborious agreement with the DC as a parliamentarian, she got the Maternity Protection Act (1950) passed, which aimed to provide tools to safeguard jobs and wages for working mothers[43]. At the beginning of 1946, Noce was called to take charge of the textile union (FIOT), thanks to her previous experience as a tailor. It was in this role that she was chosen into the Italian delegation invited to the USSR to visit metallurgical and textile factories[44]. She later became president of the Warsaw-based International Union of Textile and Clothing Workers and attended several conferences in Europe. These were years of trade union turmoil that led to the signing of the first national contract concerning the physical and economic protection of women textile workers and mothers. During the Scelba government (1954-1955), she faced the crisis in textiles at the head of the union, which led her to deal with the great downsizing of the workforce in the sector[45].

They were issues that also guided her work during her second term as an MP (1953-1958), during which she dealt mainly with wages and salaries, proposing to set a minimum wage for all workers[46].

[37] Massimo Massara (a cura di), I comunisti raccontano. Cinquant’anni di storia del PCI attraverso testimonianze di militanti. 1945-1975, vol. I, Teti, Roma 1975, p. 49.

[38] Teresa Noce, Rivoluzionaria professionale. Autobiografia di una partigiana comunista, Red Star Press, Roma 2016, p. 328-332.

[39] Renzo Martinelli e Maria Luisa Righi (a cura di), La politica del Partito comunista italiano nel periodo costituente. I verbali della direzione tra il V e il VI Congresso 1946-1948, Editori Riuniti, Roma 1992, p. 104.

[40] Fondazione Istituto Gramsci Emilia Romagna, Fondo Teresa Noce, b. 1, fasc. 4, Programma del Pci per la Costituente. Contro il fascismo per la Repubblica e la democrazia votate il Partito comunista, giugno 1946.

[41]Guido Gerosa, Le compagne. Venti protagoniste delle lotte del Pci dal Comintern a oggi narrano la loro Storia, Rizzoli, Milano 1979, p. 27.

[42]https://elezionistorico.interno.gov.it/index.php?tpel=C&dtel=18/04/1948&tpa=I&tpe=I&lev0=0&levsut0=0&levsut1=1&es0=S&es1=S&ms=S&ne1=13&lev1=13

[43]Fondazione Istituto Gramsci Emilia Romagna, Fondo Teresa Noce, b. 1, fasc. 7, La prima legge democratica della Repubblica italiana, s.d.

[44]Teresa Noce, Rivoluzionaria professionale. Autobiografia di una partigiana comunista, Red Star Press, Roma 2016, pp. 336-339.

[45] Fondazione Istituto Gramsci Emilia Romagna, Fondo Teresa Noce, b. 1, fasc. 6, Per difendere il nostro lavoro e il nostro pane, una sola via: la lotta!, s.d.

[46]Teresa Noce, Rivoluzionaria professionale. Autobiografia di una partigiana comunista, Red Star Press, Roma 2016, pp. 342-345.