Written by Mariachiara Conti

Early years

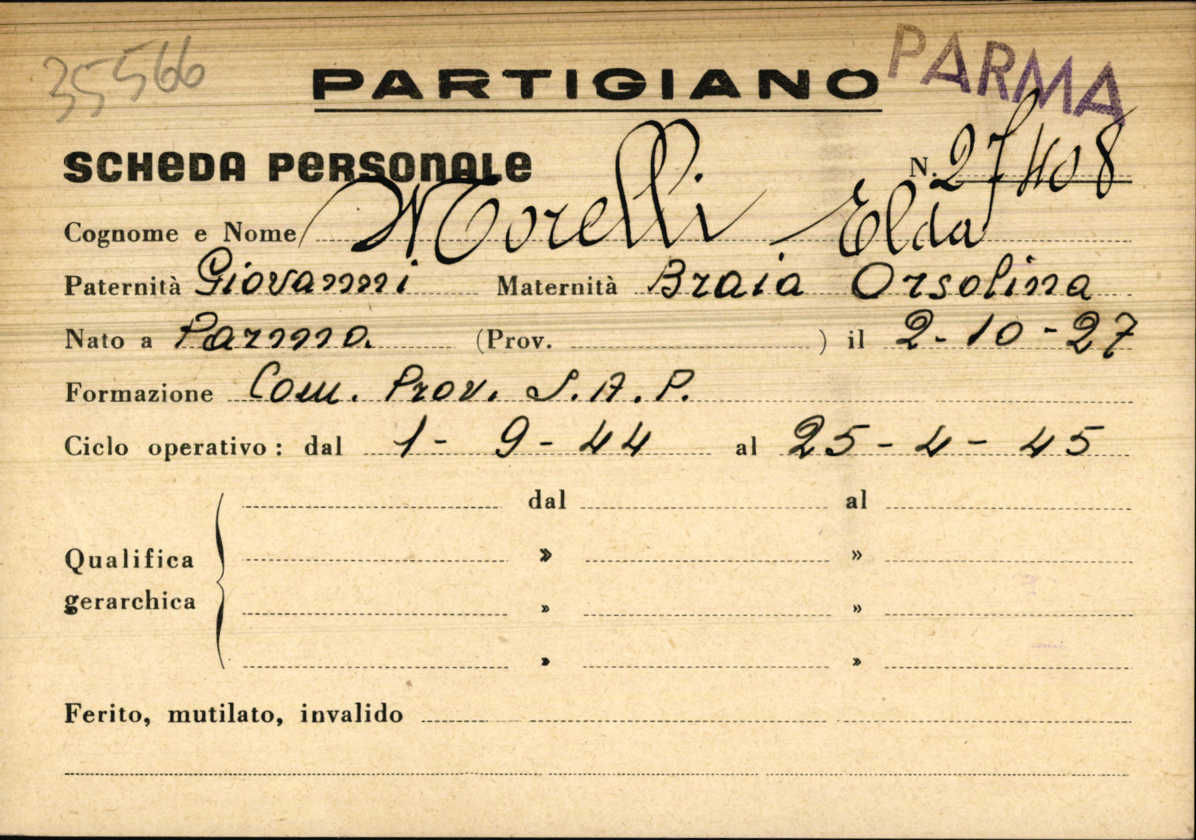

Elda Morelli was born in Parma to a family of humble origins: her mother Orsolina Braia was a worker in the Borsari factory, where perfumes were made, while her father, Giovanni Morelli, was a seasonal upper cutter for various clients in the city [1].

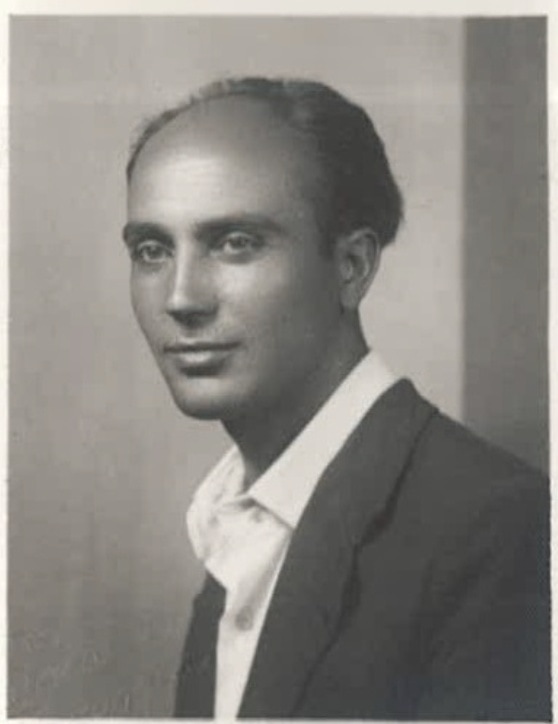

Morelli was a longtime antifascist: in October 1932, when Elda was only five years old, he had been reported to the Special Court for charges of belonging to the Communist Party and being one of its main organizers in the province. In particular, he had been charged with guaranteeing connections between Parma and Fidenza, distributing prohibited press and weapons, and having direct contact with Antonio Raise, an emissary of the PCI who had returned to Italy to get the organization back on its feet in the northwestern provinces [2]. He remained only a few days in prison, however he was amnestied for the tenth anniversary of the March on Rome, although he continued to be under surveillance during the following years[3]. By the end of the 1930s he had apparently remained inactive, though he gave no signs of repentance and continued to hold the same communist views [4].

Although the Morelli family was originally from Oltretorrente, where the anti-fascist movement had been particularly present during the 1920s, they lived in the working-class Molinetto neighborhood on Via la Spezia, near the monumental cemetery close to the city[5] Elda grew up in a lively anti-fascist environment, thanks to her father’s acquaintances. Among them was former Commercial Bank employee Bruno Longhi, who was also arrested in 1932. Between 1936 and 1939 Elda had gone to his home together with other comrades in order to listen to developments in the Spanish War on the radio[6].

Intellectual and political awakening

After completing her studies at the Filippo Corridoni elementary school she decided with the support of her parents to enroll in the Gian Domenico Romagnosi Classical High School, one of the oldest and most prestigious in the city, generally attended by the children of the wealthier classes: “For me it was not traumatic if I have to tell the truth,” she recounted, “I still have my closest friends, who were my schoolmates, as it is usually the case. I almost never felt this marginalization.[7]

She started in 1937 and attended Course B, where she got to know several professors who, though not openly expressing it, were pleading the cause of anti-fascism[8]. The best known of these was the Greek and Latin professor Ferdinando Bernin. He was already on file with the Police in 1914, because he was believed to carry out anti-militarist propaganda and having a great deal of influence on the workers of San Secondo, a town in the Parma lowlands in which he resided. Belonging to the reformist wing of the socialists, he had been in close correspondence with Ferdinando Bernini -then editor of “L’Avanti” and a revolutionary socialist-regarding Italy’s participation in World War I[9]. In 1916 he became the provincial secretary of the PSI and was an active militant until the November 1920 municipal elections, when he was elected opposition councilor in the City of Parma[10]. Starting in 1923, with the final establishment of Fascism, he retired to private life, showing apparent indifference to the Regime[11]. After a brief teaching experience in Arpino, in the province of Caserta, from the 1923-1924 school year he served as a full professor at the Liceo Romagnosi[12] Here – some of his former students recalled – he used to use classical texts to lecture against tyrants who exercised power arbitrarily or against war, arguing that “men are less wise than ants, who, when they find an obstacle they scan it, unlike human beings who fight against each other with increasingly destructive weapons”[13].

Instead, Elda Morelli recalled that: “This Ferdinando Bernini wrote Latin vocabulary and taught Latin and Greek. When I first met him he was a rather disliked man, however he had also been nice, very good, his daughter had told me later that he was very bitter: he had always been a socialist, but he was an intelligent man, a bit transgressive, done in his own way, even in the way he taught, a man of value without a doubt, however he no longer cared to arouse sympathy. He was a bit disheartened: when things became denser he had to run away, he was known as an anti-fascist and so were the others.”[14]One of the others was liberal Francesco Franco, professor of history, Catholic close to the DC Olimpio Febbroni, professor of literature and later a member of the provincial CLN, and substitute teacher of literature, Gavino Cerchi, a communist, killed by the Nazis in the Colorno massacre on March 28, 1945[15] [16].

However, professors loyal to fascism were also by no means absent: “The only ones who were fascists, ridiculous, were the gymnastics teachers and professors, but they were pitiful because they were just so at a fanatical level, I remember. There was Archilluzzi who also did some propaganda and then the art history professor, was also a fascist, her name was Giovannini and she also knew very little about art history.”[17]

Silent resistance in WWII Italy

When the armistice was signed (September 8, 1943), with the resulting German repression, the Morelli family was displaced near Sant’Ilario, in the Reggio Emilia area. The temporary house began to turn into a refuge for straggling men and a place for nightly meetings with the usual comrades, friends of her father. Elda soon realized that a real clandestine activity was being organized and asked if she could do something, but received a very unenthusiastic answer from Giovanni Morelli: “now we’ll see!” Nevertheless, secretly, together with some friends she began to do some “girl’s” work i.e. liaison for the partisans, strictly by bicycle, because “it was all a climate, I don’t know for example you had two or three guys who would stay two days because then they had another address.In the house there were meetings, you couldn’t remain a stranger.”[18] Elda’s father was a real clandestine person.

When she returned to Parma, presumably in October 1943, Elda got in touch with the Communist Party’s Agit-Prop, a branch of political work at which her father’s friends, leaders such as Bruno Longhi (Fulvio) and Edgardo Carli (Sandro), the deaf partisan, worked: “They sent me to this Sandro who lived on Via Milazzo with his pregnant wife, to learn how to use the mimeograph and to learn how to draft manifestos to throw. And so he taught me how I had to do it, because the first experiment was this. He said, “Come on! Stand there and write down what country it is!” So I was a sophomore in high school and I wrote. I was writing some wrapping paper, he was walking around, hustling with his wife. Finally when he read this little work he said to me, “No! You’ve got it all wrong! Homeland is a rip-off!” He taught me to be a little more succinct. These were very crude things, in short appeals, buzzwords and that’s it to be thrown around like that.”[19]

After learning the writing technique and the use of the mimeograph, the reams of paper, typewriter and cliché were moved to Edgardo Carli’s in Via La Spezia so that Elda could do the work during her free time from the studio in her room. In the small makeshift workshop she thus printed the official sheet of the communist federation of Parma, “La Riscossa,” as well as leaflets calling out workers to go on strike “against the German occupation,” “against the embezzlement of resources,” and “against the massacres of civilians” that were taking place in the province[20].

Once ready, the materials to be distributed were circulated in the addresses provided by “the Deaf” and delivered by Elda as if they were simple packages. If they were instead posters to be pasted, she would go to the agreed meeting place of the Church of the Annunziata and deliver them to other girls who would then each post them in a different sector of the city[21].

Beginning in early 1944, the activities of Giovanni Morelli – who had become one of the leaders of the PCI in the city – intensified and it became very risky to keep that compromising equipment at home. Hence Elda moved the mimeograph first to the cellar of one of her classmates on Pomponio Torelli Street, then, she placed it on Mazzini Street in the bombed-out house of an old monarchist lady, “l’Angioletta”[22][23]. When the latter realized the type of leaflets printed and the danger she was facing, she decided to revoke her availability and the mimeograph found another permanent location. Elda dragged the heavy contraption, hidden in a wood sack, together with the very young partisan Maria Bocchi “Kitty,” along the Lungoparma and crossed the entire historic center patrolled by the Black Brigades, to the Palazzo della Pilotta where the Palatine Library was located[24][25]. Her classmate Edoarda Masi, daughter of the director, opened the door for her. She also hid the mimeograph among the books banned by Fascism that, Elda together with her father was trying to save from destruction in order to preserve t the cultural heritage of the prestigious library intact[26].

Stealth and solidarity: Underground resistance activities

Starting in the summer of 1944 Elda also took on liaison duties framed in what would become the 78th Patriotic Action Squad (SAP), operating between Parma and the Ceno Valley, a formation of which Giovanni Morelli was also a member of.This was a Brigade that carried out tasks in support of the armed struggle, made up of regular partisans by day and irregulars by night[27]. This characteristic allowed her to continue attending the third classical high school, altough with reduced attendance to two, three times a week in the premises of the Convitto Maria Luigia, since the old Romagnosi premises, being located near a bridge, had been bombed[28][29].

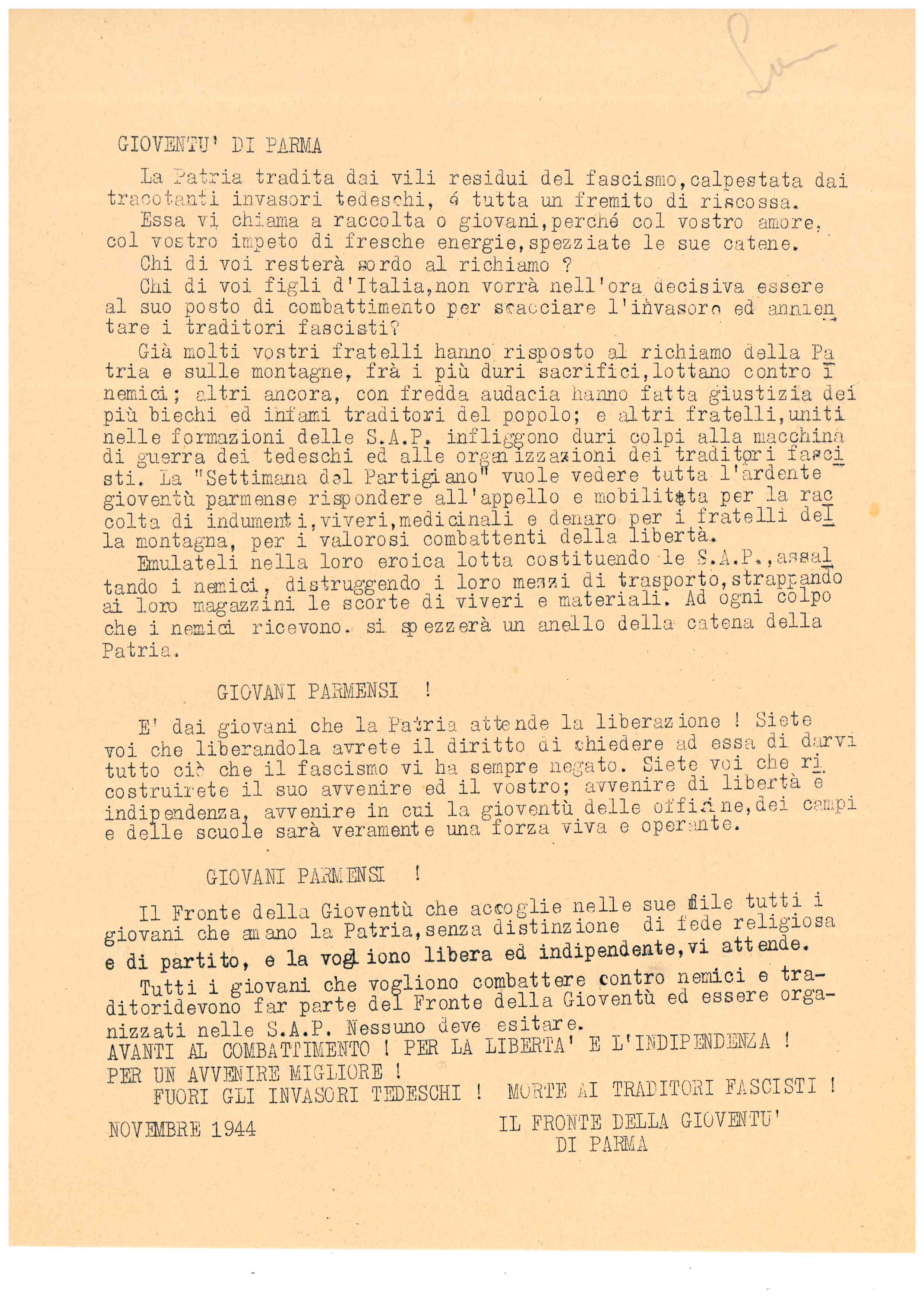

Elda kept in touch with the partisan movement in Sant’Ilario and with the Fronte della Gioventù (FdG), a mass organization that had the task of getting young people to join the Resistance struggle and to involve them in social struggles. Their representative was Enrico Ghinelli (Renato): “I was scared when I had all the material ready and had to take it with Ghinelli from the Fronte della Gioventù! Ghinelli was someone who was once at the appointment and twice he was not. And so, we’re already talking about November 1944-January 1945 and it was really tragic, and were also checkpoints there then, just two Germans or two from the black brigade would stop you, look inside your bag – you know I had those big bags full of corncobs – at two, and that’s all you had to do, so you would go like that. […] So when Ghinelli wasn’t there, what did I do with that stuff there that was so bulky? I would go to the nursery and bury it!”[30][31]

Orsolina Braia, aware of the risks her daughter was taking, would follow her on her bicycle, at some distance, and as soon as she had finished the distribution she would accompany her to the Bixio barrier kiosk to sip a tangerine punch to replenish her strength[32].

On February 14, 1945 Giovanni Morelli was arrested by the SD (Sicherheitsdienst) in the small baby shoe store he had opened on Bixio Street to escape unemployment: the workshop, known to the German police as a communist hangout, thus became a trap into which other Sappists fell. Bruno Longhi was arrested and taken to the premises in Via Campanini, secondary headquarters of the SD, where he died the next day from torture suffered in an attempt to extort information from him.

Young barber and Communist militant Romeo Reverberi, upon entering, realized the trap and tried to escape but was hit by several revolver shots, dying instantly. Other Sappists would repair to the mountains to escape the chain of arrests[33].

In mid-March Giovanni Morelli was captured along with others andtransferred to the Bolzano transit camp[34].

At this point Elda had to suspend all her activities to avoid further “falls” and because she had became totally disconnected from the organization[35]. She waited, together with her mother, for the Liberation of Parma, with the anguish of not knowing the fate of her father who would return to the city on foot only on May 8, 1945[36][37].

Elda Morelli’s post-war path

At the end of the war, Elda received her classical high school diploma and later enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Parma. After obtaining her degree – in progress and with honors – she practiced medicine first in the microbiology laboratory at the University of Parma, then in the Hygiene and Prophylaxis laboratory until becoming head physician in the Civil Hospital in Colorno and director of the Micron laboratory in Reggio Emilia. After the war she was no longer involved in politics. She died in Parma on September 18, 2023[38].

Sources

Sources and Bibliography

- ACS, CPC, b. 540, fascicolo Bernini Ferdinando.

- ACS, CPC, b. 3399, fascicolo Morelli Giovanni.

- Archivio ISREC Parma, Fondo privato Edgardo Carli, b. 1, fascicolo Agit-Prop e volantini.

- Archivio ISREC Parma, Fondo Testimonianze, b. 5, testimonianza orale Elda Morelli, 1988.

- ACS, ACS, RICOMPART, Commissione Emilia Romagna, fascicolo Elda Morelli.

- ACS, ACS, RICOMPART, Commissione Emilia Romagna, fascicolo Giovanni Morelli.

- Dalla scuola fascista alla lotta antifascista, a cura del Liceo Classico Gian Domenico Romagnosi, MUP, Parma 2004.

- Ferdinando Bernini, dal Romagnosi alla Costituente, a cura dell’Associazione Allievi Liceo Romagnosi e del Liceo Classico Gian Domenico Romagnosi, Teatro Regio di Parma, Parma 2004.

- https://www.gazzettadiparma.it/gweb+/2023/09/18/news/elda-morelli-addio-alla-partigiana-che-amava-i-classici-732331/?paywall_canRead=true&user_canRead=true&id=9570

- Luigi Leris, 78ª Brigata Garibaldi SAP. Antifascismo e resistenza nella bassa parmense, STEP, Parma 1975.

- Marco Minardi, Ragazze dei borghi in tempo di guerra, Edizioni ISREC, Parma 1991.

- Marco Minardi (a cura di), Donne, Resistenza e cittadinanza politica. Avvenimenti, passioni, emozioni, delusioni, Benedettina editrice, Parma 1995.

- https://www.testeparlantimemorie900.it/video/maria-bocchi-parte-1/