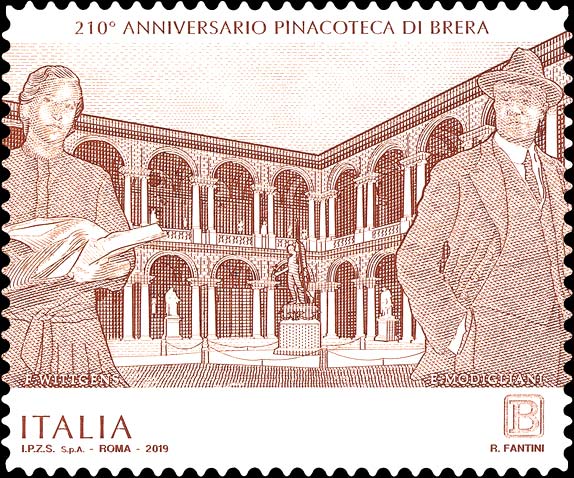

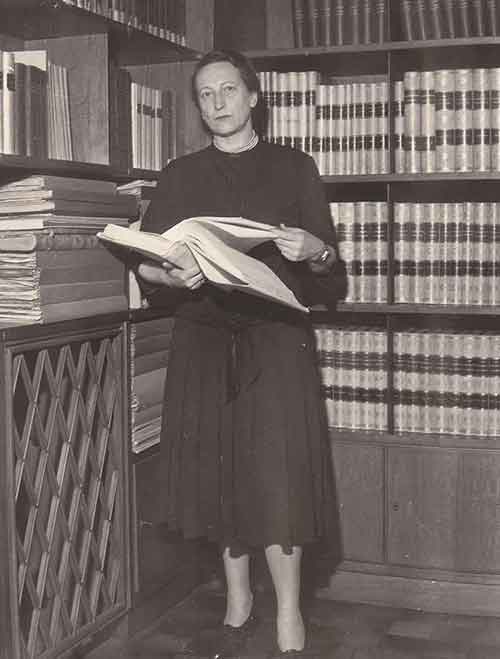

“I am Fernanda Wittgens”

The same profile was recalled by Antonio Greppi, mayor of liberated Milan in 1945, in their first meeting: “It hardly gave the usher time to announce her. And I saw a woman before me, unlike any other. A classical scholar would have imagined in her ‘Pallas-Athena’: I thought of Walkiria. She repeated the name to me, extending her hand: ‘I am Fernanda Wittgens'”.

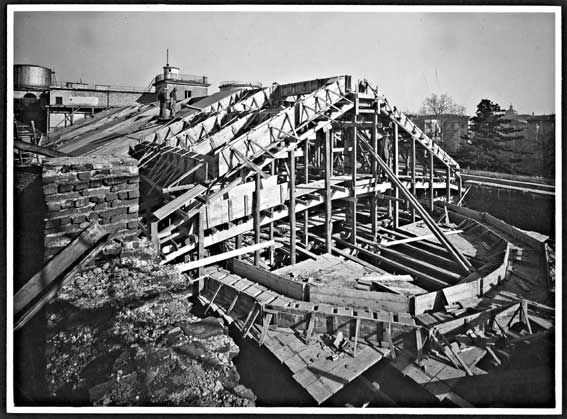

In December 1949 she was awarded the Gold Medal by the City of Milan with the following reasons: “An exceptional temperament as a citizen and artist, in the years of oppression she intrepidly faced imprisonment for the cause of freedom. At the end of the war she waited with inexhaustible faith for the work of reconstruction and rearrangement of the city’s galleries and museums, doing her utmost also to acquaint Italians with their immense heritage of art and foreigners with the true, most enlightening face of our homeland”.

Her life was always oriented towards the conservation and enhancement of the artistic heritage. Among others she was responsible for the rescue and restoration of Leonardo’s “Last Supper” and the pressure for the purchase by the Municipality of Milan of Michelangelo’s “Pietà” currently preserved in the Sforzesco Castle Museum.

Fernanda Wittgens died prematurely in 1957.

The funeral home was set up at the entrance to the Art Gallery, where thousands of people paid homage to her and signed condolence registers. She was buried in the monumental cemetery of Milan.

In 2014, a memorial stone and a tree were dedicated to her in the Garden of the Righteous. A film was dedicated to her in 2022.

This is what his commemorative plaque reads:

Generous and strong soul

Fernanda Wittgens

After the destruction of the war

She dedicated herself to resurrecting

Of the city, of culture

From the Brera Art Gallery

Implementing in the ancient institute

The modern concept of the living museum.