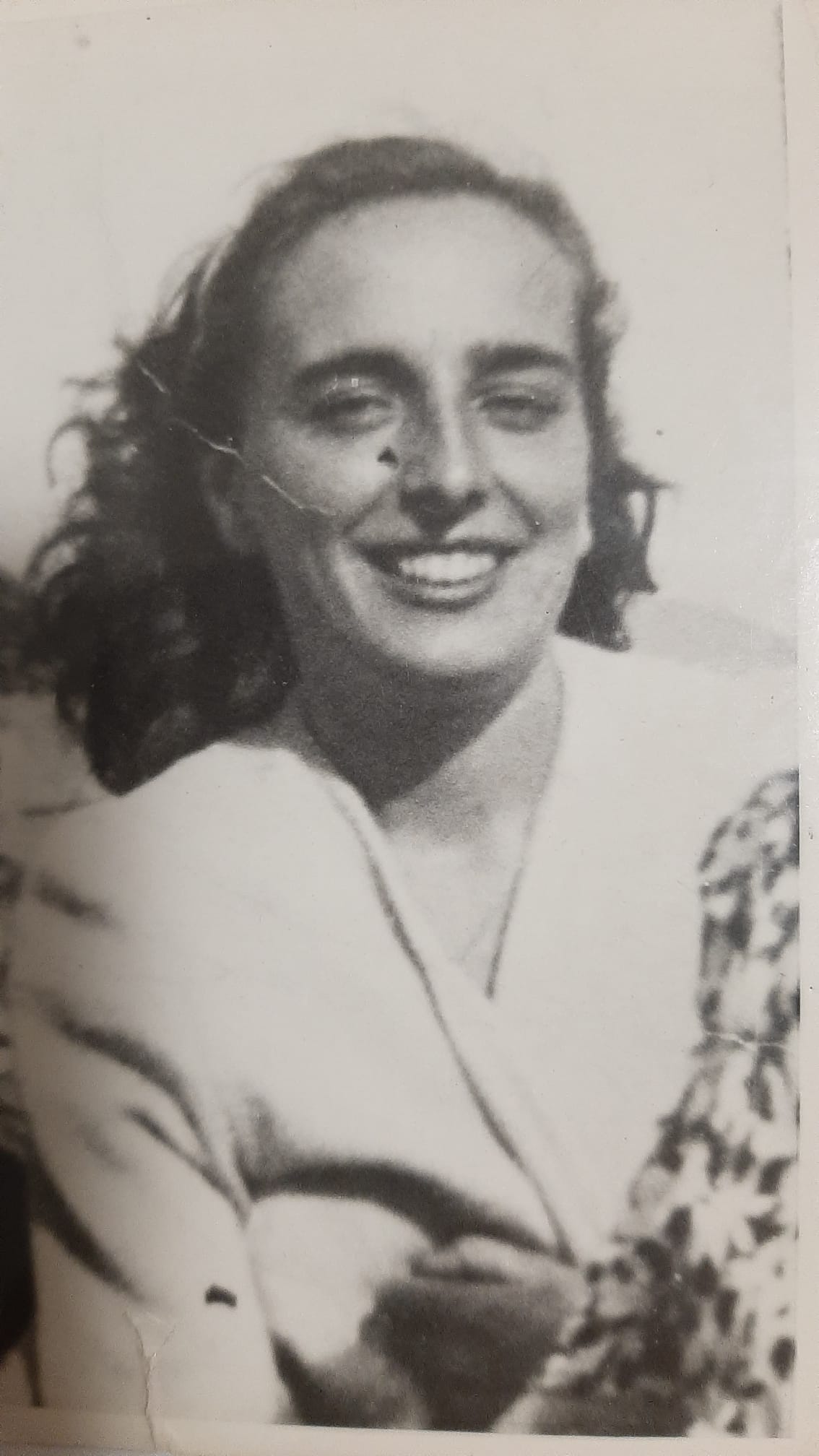

Together, brother, sister and a group of displaced friends got in touch with the resistance through the local National Liberation Committee, “we were already hearing about the Gap [Patriotic Action Groups] and the partisans […]. We let them know that we were available, so they approached us and gave us some leaflets to distribute, to leave around in doorways”. “At that moment we were beginning to become aware that we were doing something and began to collaborate”.

But the need to contribute more arised, and Pietro Ferro got the idea of forming an amateur dramatic society, which to cover they called by the term of fascist tradition “Youth”, which after the war would become “Aurora di libertà – Freedom dawn”: “At that time I had not done any action with the Resistance and we were performing comedies in Campo Ligure. However, it was because of this that we began: the earnings officially were going to the Red Cross while we were giving them to a person in Campo Ligure in favor of the partisans. This person disappeared at some point, and we got a little scared”. His name was Piero Rossi, “we thought he had gone up into the mountains, I learned only sixty years later that he had been captured and taken to Mauthausen, where he then died”.

Ferro recalls the roundup in the days leading up to the Benedicta massacre: “Of course because of a spy, they manage to find all the ambushers. That morning they broke into my house […] and took my brother to take him away. My brother thought it was for the money from the plays and the manifestos. When he went out the door and saw that it was a roundup, he gave a sigh of relief, because otherwise it would have been tragic. And where are all these young people taken to? To the station, in a cattle car. Of course the family members, especially the mothers, were all clinging to the train. But this roundup would last seven days”. Women, as in many other similar situations, were protagonists of a form of civil resistance, tried directly with their bodies to intervene to oppose Nazi and Fascist orders. Ferro continues the narration of the events, with a half-smile: “So I, there I started…as they took my brother I went to the partisan with whom we were collaborating and I said […] ‘you have to free my brother or else I will denounce you all’ he goes ‘be calm, look: […] deliver this piece of paper to the German officer’. I straddled the bicycle, crying, pedaling”. And again in another interview, “I think I set off in my nightshirt with my coat over it […], I met this German and he gave me a card that said that my brother was part of the Todt organization”. Thanks to this document and her elementary knowledge of German, she was able to get her brother off that train: “When my brother got off the train my mother and I hugged him but we felt a shame towards the others, that we took him away”. “We felt a great shame on ourselves, in accompanying him away from there, with all the people looking at us… Because he was the only one who did not leave, all the others ended up in the concentration camp”. The shame is that of not being able to free the other men, of having acted – in spite of themselves – only on behalf of their loved one with the knowledge that for the others there would be no hope. In the following days for the surrounding territory of the Ligurian Apennines, the situation worsened further when Nazi units, assisted by fascist companies, encircled the area in which the two partisan brigades, the Autonomous Alessandria Brigade and the 3rd Liguria Brigade, were operating. After some fighting, Nazi and Fascist troops managed to capture many partisans, who were shot and buried in a mass grave. The event went down in history as the Benedicta massacre.

It were these last two events, the fear for her brother during the roundup and the Benedicta massacre, that convinced her that she needed to become more active in the Resistance, “I want to do something, because I can’t take it anymore”. Therefore she began to be a courier girl carrying small arms from Campo Ligure and Rossiglione, acting as a liaison with the workers employed in the displaced optics industrial plant in the village. She carried out this activity unbeknownst to the rest of the family, even her brother, and to conceal her movements she lied by saying she had heard about distributions of goods and food.