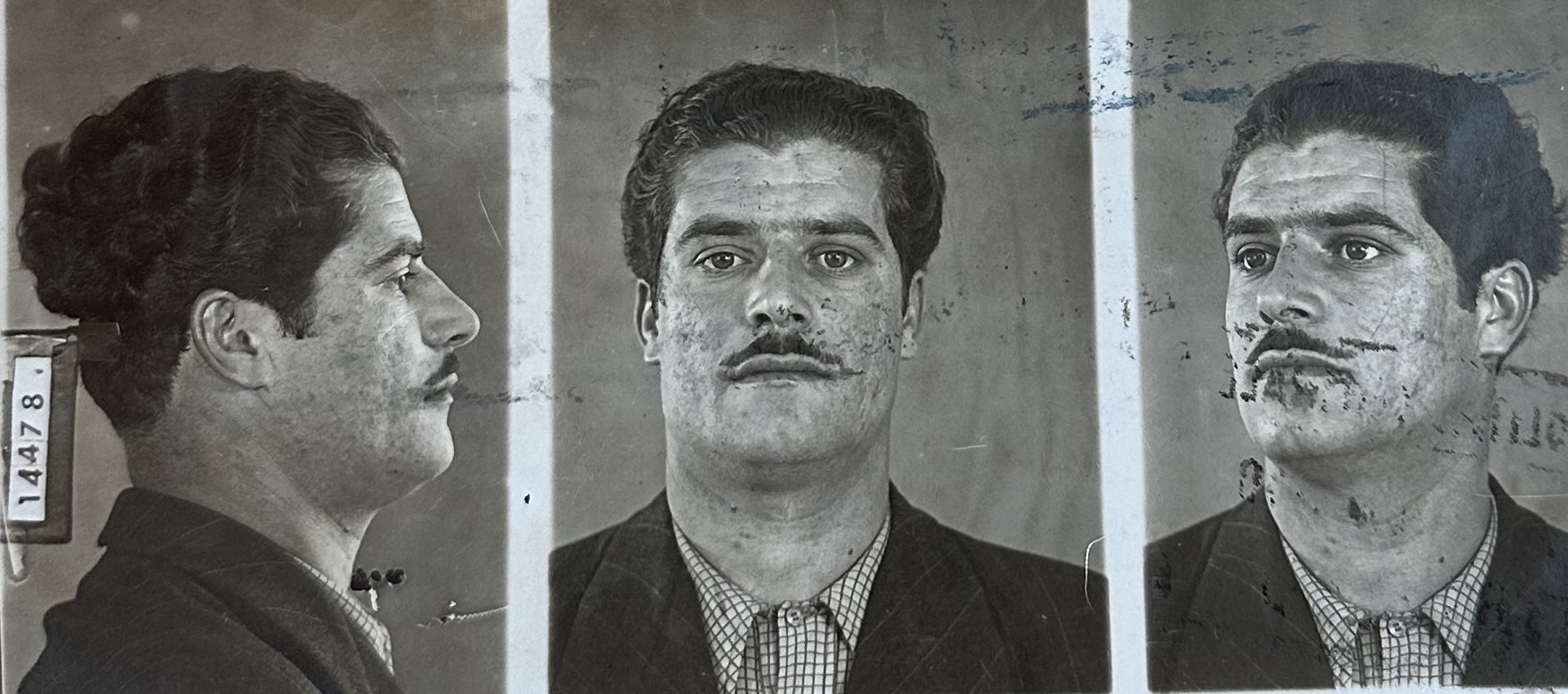

At the beginning of 1931, as she was about to get married, a wave of arrests hit the leaders of the PCI in Empoli: Remo Scappini was also spotted and sought after, but he managed to fortunately take refuge in Livorno and then expatriate, finding shelter, like many in his condition, in Paris[10] [11]. Rina was questioned several times by the police even though she was genuinely unaware of her fiancé’s fate: only a few months later did she learn from other comrades that he was in the USSR to attend courses at the Leninist School in Moscow, where he remained until the end of 1932[12].

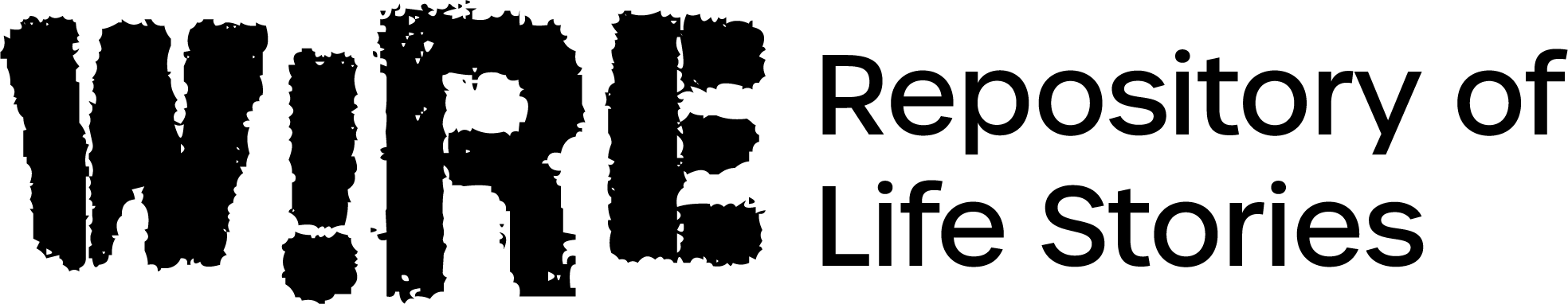

In May 1933, she took part in the civic funeral of the communist shoemaker and friend of Remo Scappini, Domenico Maestrelli – known to everyone as “Disarmament” – which turned into a demonstration against the Regime: she was thus investigated and again interrogated by the OVRA[13].

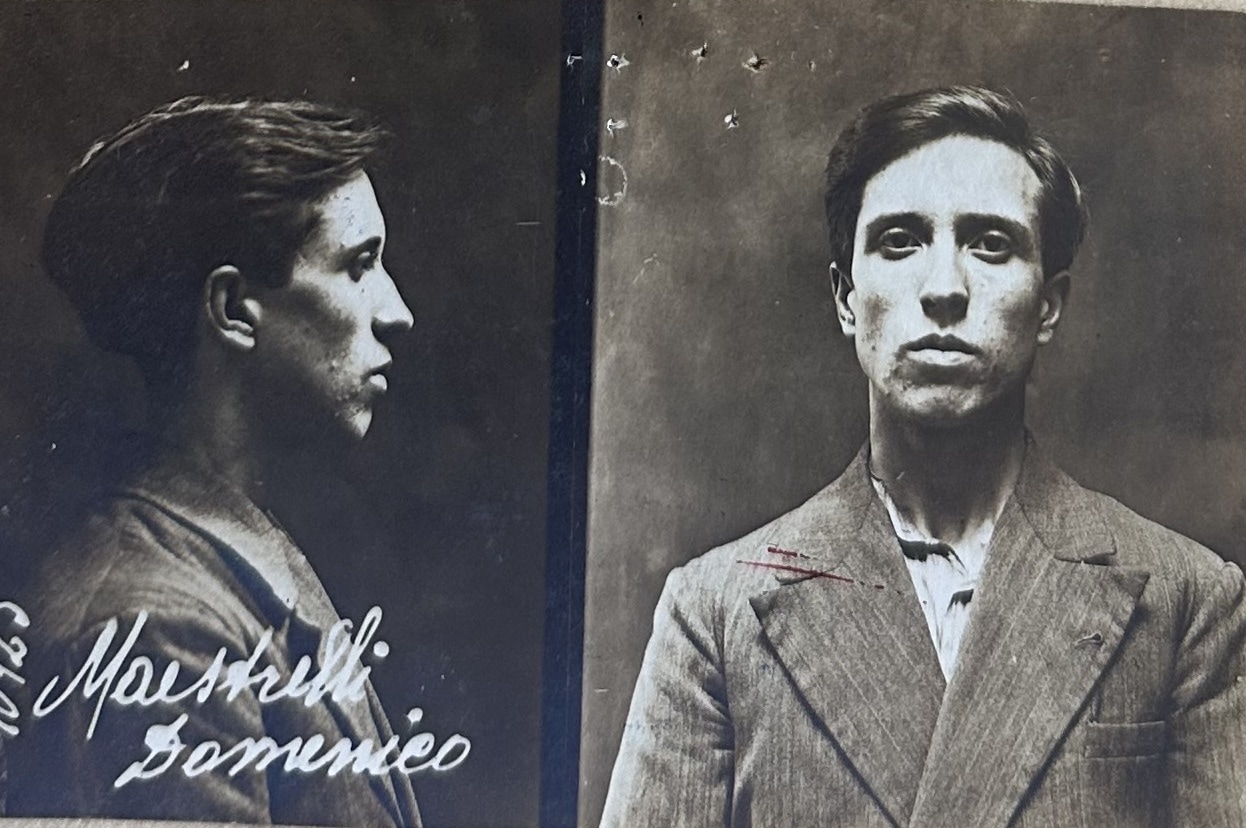

Her position worsened in October of the same year when she was taken first to the prison in Florence and then to that in Bologna to have a confrontation with her boyfriend, who had been arrested in Faenza: the police’s intention was to check whether the two had been dating during their absconding[14]. In the absence of evidence, Rina was released, but nevertheless placed under close surveillance, while Scappini was sentenced to 22 years imprisonment by the Special Court[15]. The management of the Civitavecchia prison always denied the two permission to have an interview and for nine years they only corresponded by letter[16].

She remained on the sidelines for some time to disperse her traces until she got herself employed in a military backpack factory that had developed with the Ethiopian War (1935-1936): here too she carried out trade union agitation among the workers, but at the end of the conflict the workforce was reduced and Rina fired[17].

[10]ACS, CPC, b. 4660, fasc. Scappini Remo, Bollettino delle ricerche ad nomen Scappini Remo, febbraio 1931.

[11]ACS, CPC, b. 4660, fasc. Scappini Remo, Telegramma del Consolato italiano a Parigi al Ministero dell’Interno riguardante Scappini Remo di Giulio nato a Empoli l’1 febbraio 1908, 4 maggio 1931.

[12]Remo Scappini, Da Empoli a Genova (1945), La Pietra, Milano 1981, pp. 53-61.

[13]ACS, CPC, b. 2907, fasc. Maestrelli Domenico detto Disarmo, Comunicazione della Prefettura di Firenze al Ministero dell’Interno sul funerale di Maestrelli Domenico detto disarmo, 17 maggio 1933.

[14]Rina Chiarini, La storia di “Clara”, La Pietra, Milano 1982 pp. 37-39.

[15]ACS, CPC, b. 4660, fasc. Scappini Remo, Comunicazione del Ministero dell’Interno riguardante l’arresto Scappini Remo avvenuto il 3 ottobre 1933, 15 aprile 1934.

[16]ACS, CPC, b. 4660, fasc. Scappini Remo, Richieste di corrispondenza epistolare del condannato politico Remo Scappini, 25 agosto 1934.

[17]Rina Chiarini, La storia di “Clara”, La Pietra, Milano 1982 pp. 39-40.