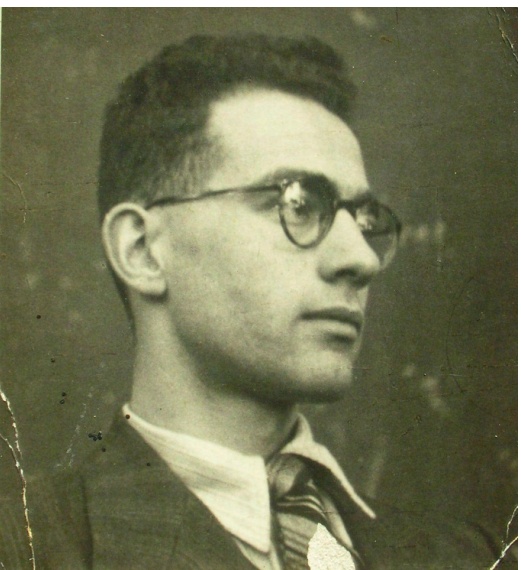

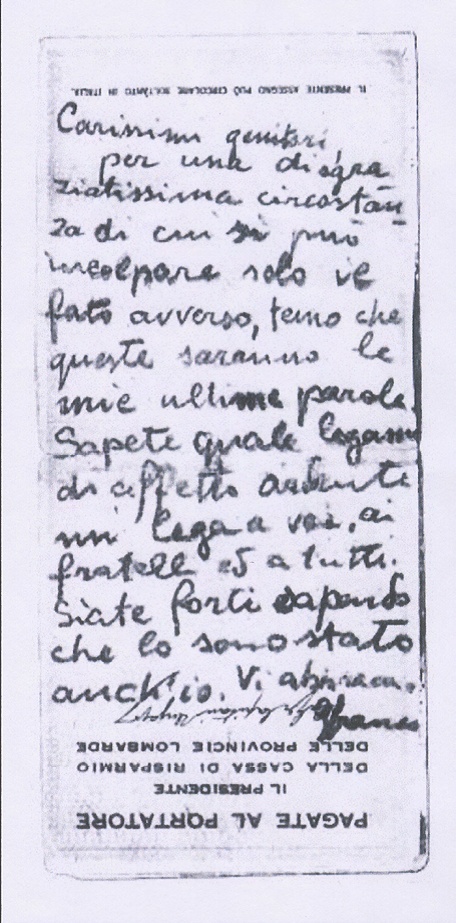

In the whirlwind of violence that war generates, the grief for her brother Gianfranco was compounded by further suffering for Teresa Mattei. En route to Rome, where she was on her way to meet and comfort her parents, she was arrested, tortured and raped by German soldiers. Thanks to the intervention of a Fascist hierarch, who freed her because he was convinced that “such a good girl cannot be a partisan”, she managed to escape and get to safety in the night, finding refuge in a convent. Mattei suffered this further violence on her own body as a woman and, like others, silently carried the marks of this episode with her, being able to recount the episode of the violence she suffered only after fifty years.

Despite the painful personal events, Mattei resumed her post as a resistance fighter, helped organise the March 1944 strikes in Florence and Empoli, witnessing the ensuing Nazi-Fascist repression with the deportation of workers, and participated in sabotage actions in the city: “The only time I wore lipstick in my life was to place a bomb. I was so unrecognisable”.

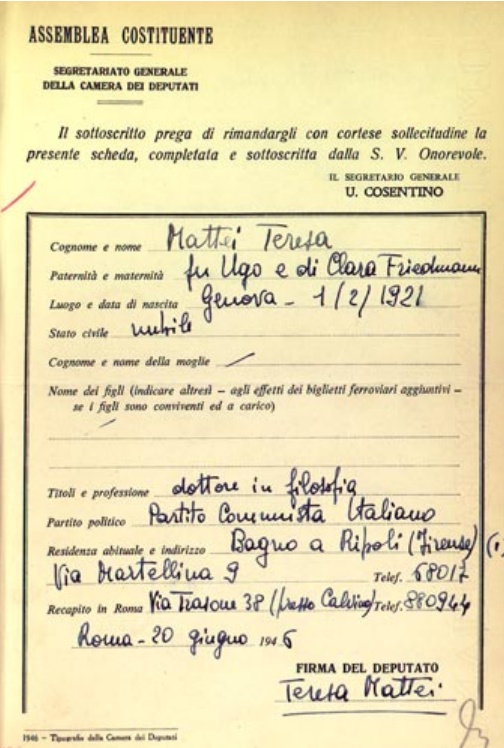

Mattei’s biography is representative of how life during wartime sometimes took dramatically adventurous forms, such as the episode that forced her to graduate early because of her activity as a saboteur; in fact, fleeing from the Germans after blowing up a convoy of explosives, she took refuge in the university, where her professor managed to cover for her by improvising with other colleagues a graduation committee, which actually validated her thesis discussion.

According to what was revealed years later, Mattei participated, although indirectly, in one of the most talked-about resistance actions in Florence, namely the killing by the Gap of the philosopher and theorist of Fascism, Giovanni Gentile, who, as a professor at her university, was pointed out by her to the resistance group.

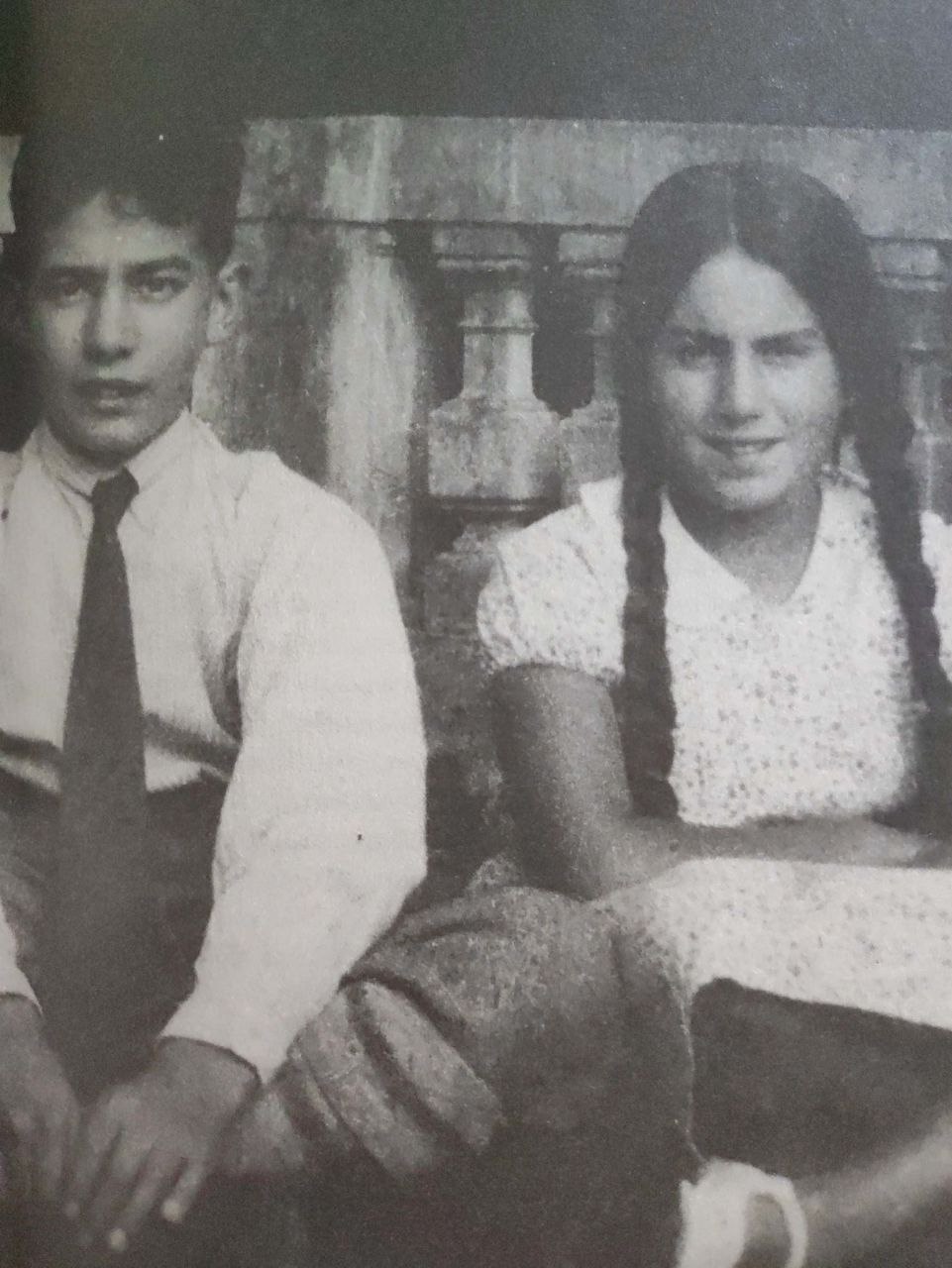

As the Allies advanced and in anticipation of the liberation of Florence, the situation in the city became increasingly complicated. While the military committee decided to aim for liberation through insurrection and, at least in the initial plans, to do so autonomously from the Allies, the Germans decreed a state of emergency, blew up the bridges over the Arno river, and besieged the city, effectively making it a battlefield with unforeseen timing and modalities compared to what the partisans had envisioned. In this context Mattei, active as a courier girl among the crossfire, was in command of the “Gianfranco Mattei” company of the Youth Front (Fronte della Gioventù), among others along with her brother Nino. “I commanded 50 partisans and on the eve of the Liberation day we were joined by many Garibaldians who came down from the mountains and some Russian, British and Scottish ex-prisoners of war who helped us. I had the respect of everyone and I was not an exception: there were many women indeed”.