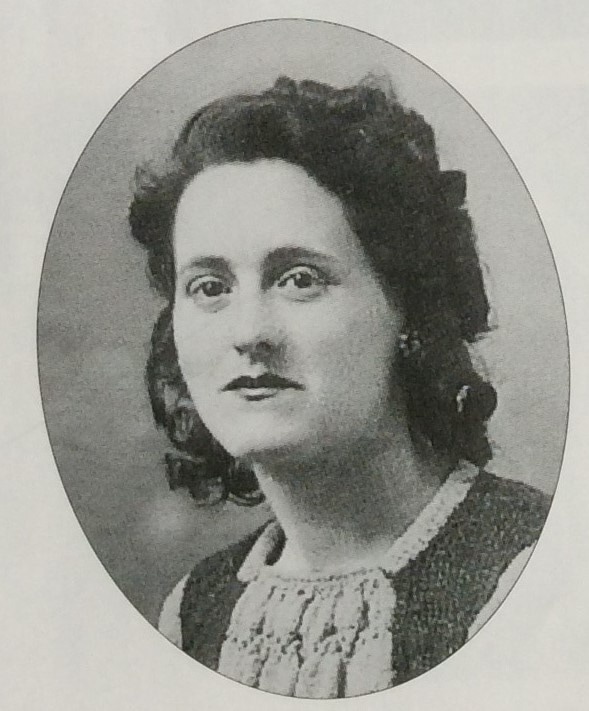

When her stepfather was exposed and had to flee to Andorra, pursued by the Gestapo, the women of the family became even more involved in the Resistance, and from April 1943 onwards they became involved with the 3rd Ariège Brigade. Maria’s mother Elvira, her sister Conxita and she herself became known as The Beleta. They continued with the logging business, acting as liaison to the Col du Py guerrillas. From their home in Peny, they took care of the allied soldiers, helping them escape across the Pyrenees, carrying parcels and making contacts between the different guerrilla groups.

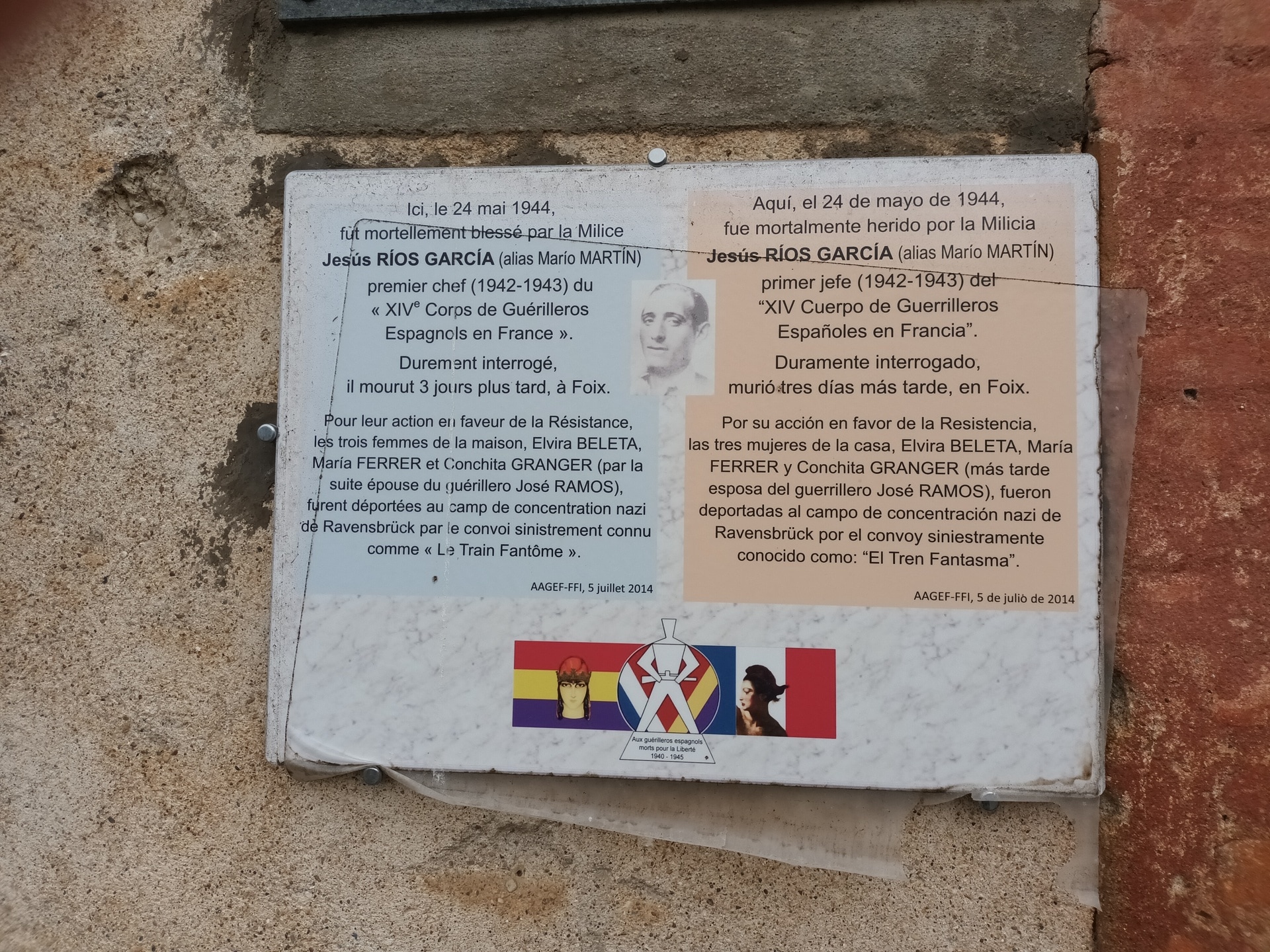

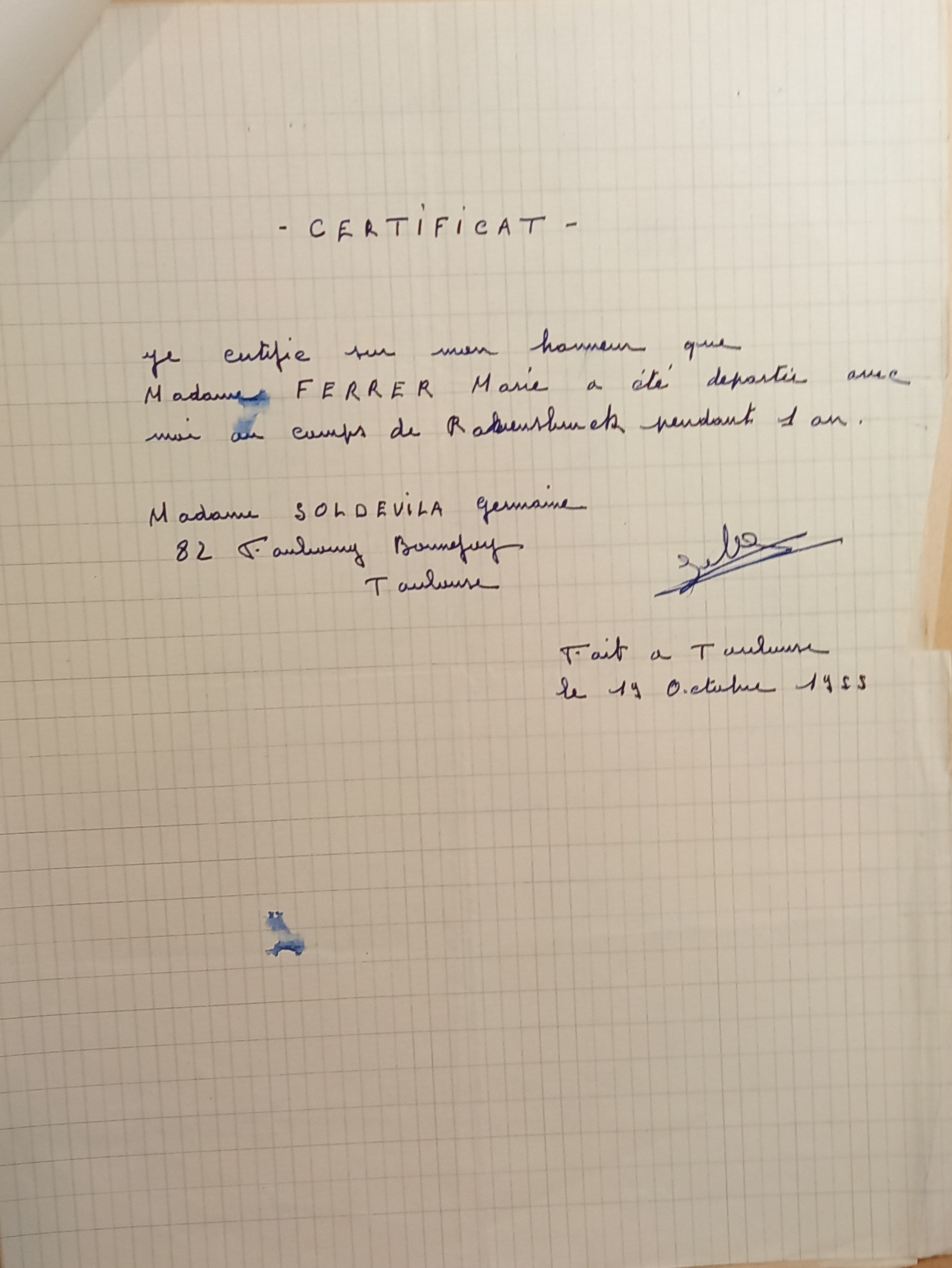

At 9 o’clock in the morning of 24 May 1944, after a raid by the French Militia [4] and a shooting at their home, the two women were arrested. At the time, they were giving shelter in their own home to a group of guerrilla fighters who were to flee across the border. Among them was Jesús Ríos, who was seriously injured. The Beleta women were harshly interrogated at the Foix prison, and then handed over to the Gestapo at the Saint Michel prison in Toulouse.

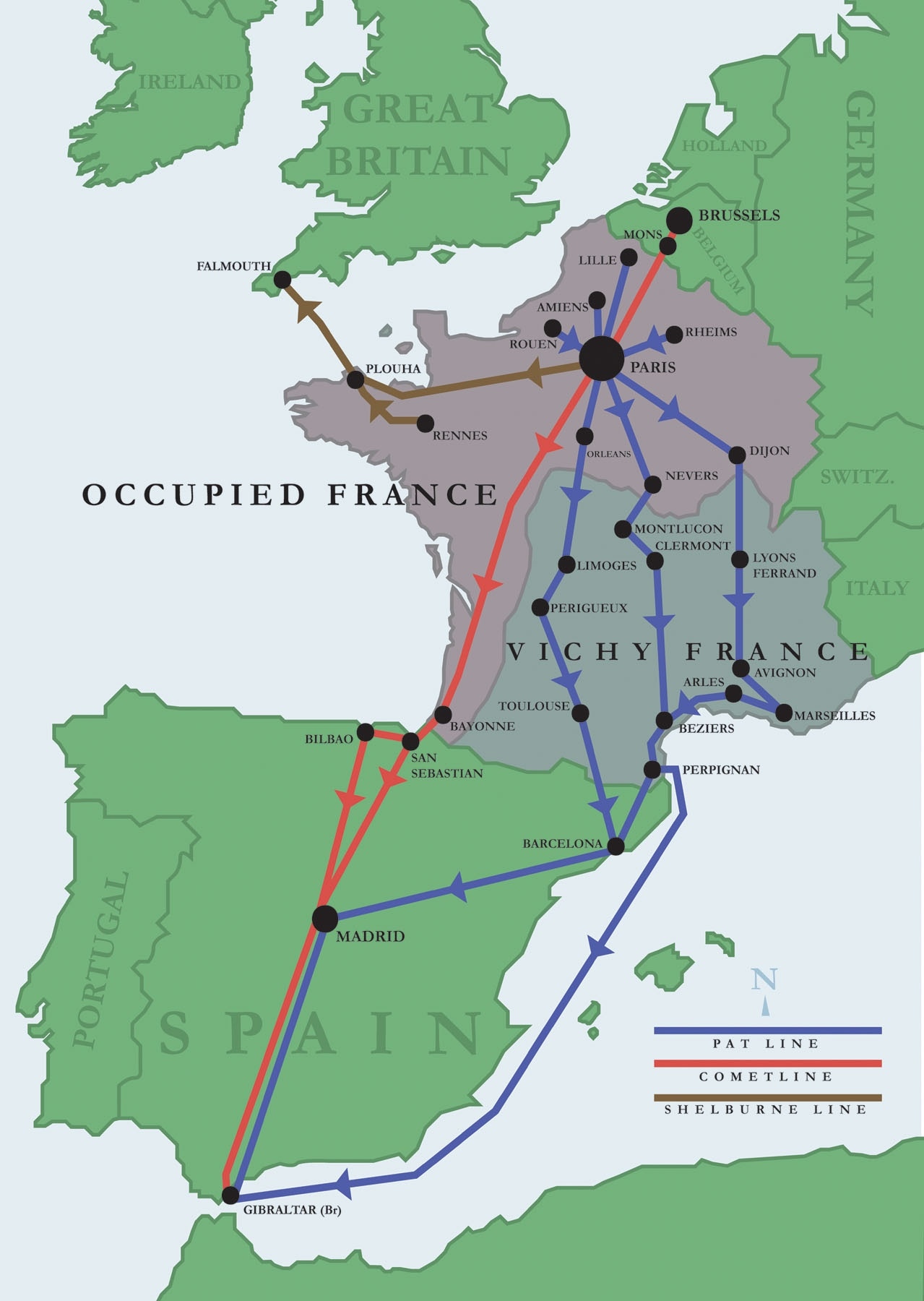

Despite the tortures, neither of the three women revealed any information about their activities and companions. The pain and the threats of execution went on for two long days, but the three women kept to the version they had agreed to when no one could hear them: the guerrillas had come to their house to have their clothes cleaned and mended; none of them knew anything or anyone. On 30 June 30 1944 they were transferred from Toulouse to Bordeaux where they were deported on board the so-called “ghost train”.

The so-called “ghost train” was one of the last transports to take its occupants to the Nazi concentration camps. And there began a journey that, according to Nazi plans, was intended to reach the Dachau concentration camp in three days. The train began its journey by transporting the prisoners in trucks from the Vernet d’Ariège camp to Toulouse. Once there, they were joined by prisoners from the Saint Michel prison and by approximately twenty women from nearby camps, among whom there were also other Spanish women. The train left Toulouse on 3 July 1944 with 750 deportees, 221 of whom were Spanish, and finally reached Dachau on 28 August 1944, 54 days after its departure. The relentless bombardments by the Allies, combined with the attempts of sabotage by the Maquis to free the prisoners, slowed down the journey, hindered by a constant back and forth in deplorable conditions. The prisoners were besieged by hunger and thirst, the conditions in the train were inhuman and got even worse when the train stopped for days as the summer heat hit hard. The wagons had no air vents and were overcrowded with people who had no place to relieve themselves or to sit, and had almost nothing to eat or drink. In addition to that, due to constant attacks which managed to block the train in some sections, the prisoners had to endure long walks and continuous train changes under the harsh repressive conditions already imposed on them.

[4] The French Militia (Milice Française) was a paramilitary organisation, converted into an official army, created on January 30, 1943 by the French government of Vichy with the support of Nazi Germany, with the aim of fighting the French Resistance and thus unburden the Schutzstaffel (SS) and the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) in their actions