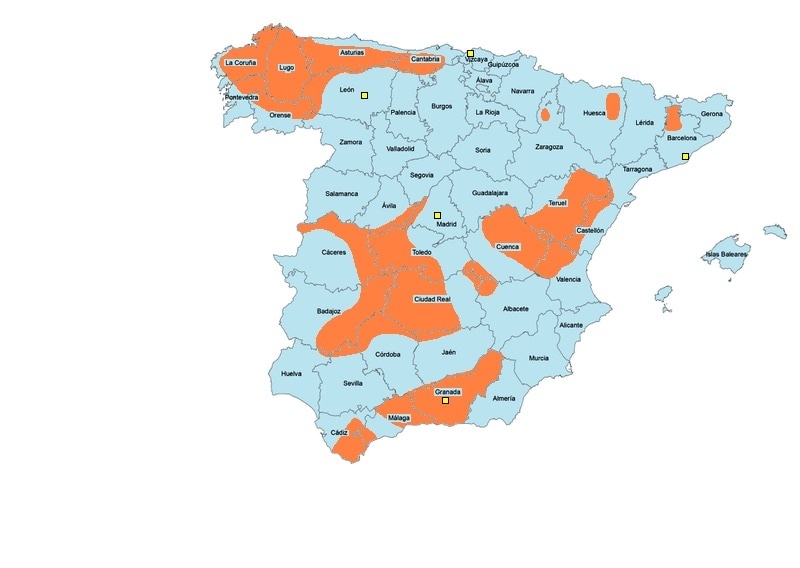

They moved all over Sierra Morena, from Córdoba to Jaén, and through Ciudad Real. They would set up camp in Mañuelas, Cardeña, La Víbora and the Alcúdia valleys. Their life in the mountains was marked by persecution and the permanent danger of being denounced or running into the Guardia Civil. And then, there were also their precarious living conditions, the lack of food and supplies, and the harshness of living out in the open air exposed to the cold, wind and rain. They fed on what they could steal from the farmhouses and on raw chickpeas. As she herself mentioned in an interview: “We lived very poorly, with a blanket on the ground and little more. We couldn’t make a stop anywhere so that we wouldn’t be discovered”. During that time, unlike other guerrilla fighters and because she was a woman, La Parrillera never carried weapons; her companions would not let her.

In the middle of 1943, Manuela became pregnant again. She had to give birth all alone in the first months of 1944 on the banks of a river, while the rest of the squad stood guard nearby. In her own words: “I tied his belly button myself and cut it out. I also washed and tended him.” Barely 8 days after giving birth and concerned about their chances to ensure the baby’s survival in the mountains, without food and in constant movement, they had to abandon him. They left him at the Molina Fernández farmhouse with a handwritten letter from his husband. But in the end, they decided to hand him over to the Guardia Civil. He later died in hospital before his first birthday.

On 27 February 1944, while trying to get some food at the El Tibio farmhouse (Ciudad real), her husband was fatally shot by the Guardia Civil. They had shown up in broad daylight, desperate and starving to death, unaware that a detachment of the Guardia Civil was inside the farmhouse. According to historian Francisco Moreno, “Alfonso “El Parrillero” entered the farmhouse and found the guards playing cards. He had no choice but to stop them and order them to raise their hands. The guards pretended to obey, but one of them threw a stool at Alfonso, while the others ran to grab their rifles. The assailants fled, but on the esplanade of the farmhouse, covered with snow and with no natural defences, Miguel “El Moraño” or “Parrillero” was shot down by enemy fire, while his companions, in desperation, run into the thick of the forest.” Manuela, together with her brother Alfonso and “El Lobito”, continued to be part of the group, now under the leadership of Inocencio “Borrica”, although they participated occasionally others, such as “Álvarez”’, “Coqueo” and Pablo González, decided to leave the band.