July 25th 1943, the day of the fall of the Fascist regime, caught her on a train bound for Novara: her family had been living in an apartment near the central station but Allied bombing had necessitated her displacement to Baraggia di Suno, near Lake Maggiore. Once back in the city, she attended the festive popular demonstrations for the fall of Fascism, but the belief that the war was over and that normal life would soon return was short-lived[9] . Her father, Giacomo Brisca, had been recalled to military service a few months earlier, as he was on leave from the army and therefore still eligible for enlistment[10]. With the signing of the armistice and the arrival of Reich troops in the city (September 12th 1943), Lidia’s father was disarmed and deported to Poland[11]. After refusing to take the oath to the Republic of Salò –the new Fascist government– he became a Military Prisoner (IMI) and only saw his family again when the war ended after two winters spent in the Stalag[12].

Giacomo Brisca’s deportation forced the family unit to return permanently to Novara, where they could count on a network of solidarity that would guarantee their livelihood[13].

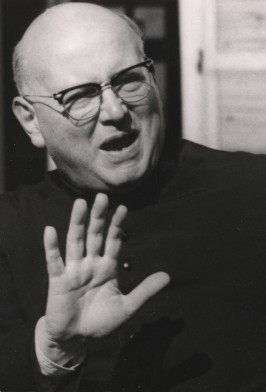

These tragic events allowed Lidia to make a final decision: “Already since the end of September,” she wrote, “I have decided that I want to act: I want to get in touch with the partisans, I want to do something to help the Jews, I want to do something positive against Nazism, against Fascism, and I try to listen, to see and to learn. I am a member of FUCI and we have big debates under the direction of Don Gec, our assistant: we decided that if they ask us to join the GUF (Fascist University Groups) we will suspend our studies: before July 25th, membership was a kind of mechanical formality, now it would become adherence to reborn Fascism, it would mean siding decisively with Hitler. We also discuss a lot whether the government of the new Fascist republicans is legitimate and come to the conclusion that it is not. Thus, the boys are bound to disobey, if they are recalled and it must be arranged how to hide them and how to send them to the mountains”[14].

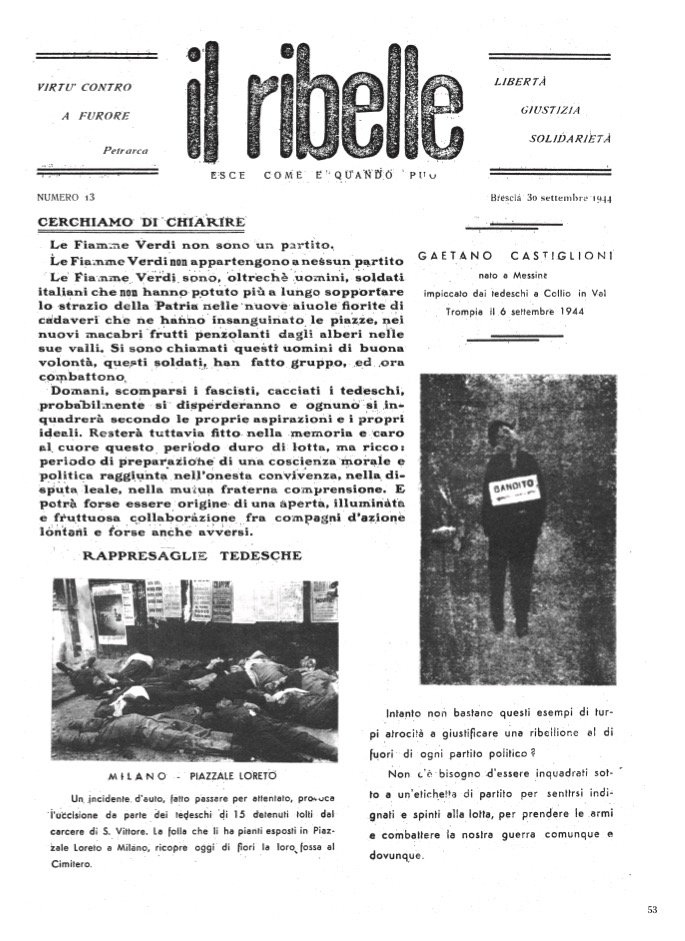

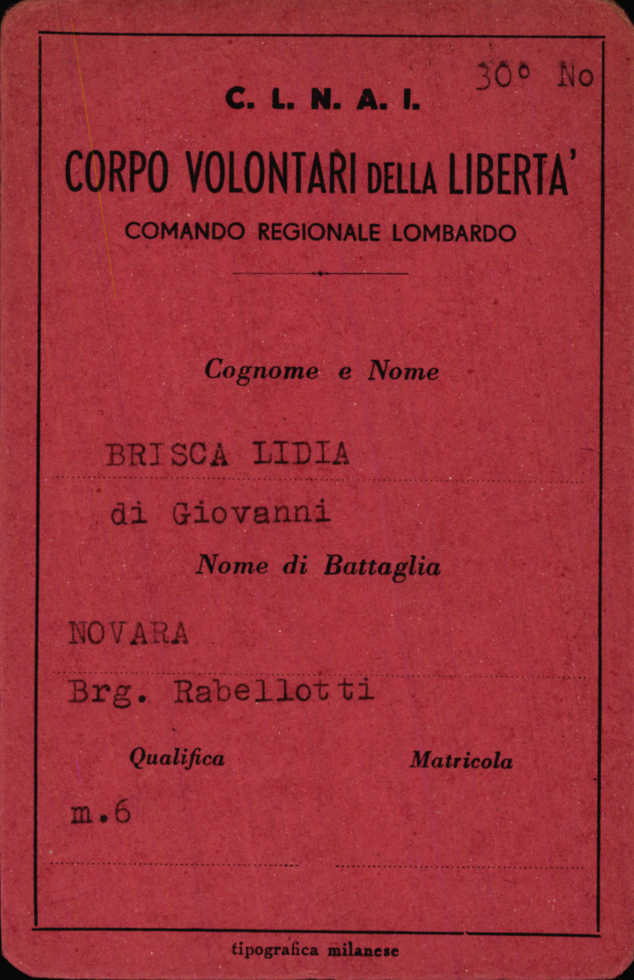

Through Don Giacomini, her high school religion teacher, she was introduced to the first Catholic-inspired partisans who were organising in the city. Since as a university student she had to shuttle between Novara and Milan, she was used as a courier girl[15]. After getting herself a new bicycle and taking on the battle name of “Bruna,” she transported medicines, carried information to the mountains, accompanied some Jewish boys to the Swiss border and distributed “Il Ribelle”, an information periodical of the Catholic “Green Flames” formations, as she recounted in her autobiography: “So with the shopping basket on the handlebars of the trusty bicycle, the missalino inside and a packet of “Rebels” casually rolled up, I went out when it was still night and there were obviously no lights in the streets. At certain gates or doorways I knew, I laid down a newspaper; then I ran to get in line at the still closed store and with one meat packet more and one newspaper packet less, I went to Church (bicycles can be brought in). When I came back I felt Iike I have lived enough”[16] .

[9]Lidia Menapace, Io, partigiana. La mia Resistenza, Manni, Lecce 2014, p. 39.

[10]Barbara Bachelloni, Enzo Orlanducci, Nicola Palombaro, Rosina Zucco, Secondo Coscienza. Il Diario di Giacomo Brisca (1943-1944), Edizioni ANRP, Roma 2007, p. 131.

[11]Barbara Bachelloni, Enzo Orlanducci, Nicola Palombaro, Rosina Zucco, Secondo Coscienza. Il Diario di Giacomo Brisca (1943-1944), Edizioni ANRP, Roma 2007, p. 132.

[12]Barbara Bachelloni, Enzo Orlanducci, Nicola Palombaro, Rosina Zucco, Secondo Coscienza. Il Diario di Giacomo Brisca (1943-1944), Edizioni ANRP, Roma 2007, pp. 192-193

[13]Lidia Menapace, Io, partigiana. La mia Resistenza, Manni, Lecce 2014, p. 56.

[14]Lidia Menapace, Io, partigiana. La mia Resistenza, Manni, Lecce 2014, p. 59.

[15]https://www.memorieincammino.it/fonti/lidia-menapace-ricordi-dellattivita-di-staffetta-partigiana/#prettyPhoto%5Bmixed%5D/0/#

[16]Lidia Menapace, Io, partigiana. La mia Resistenza, Manni, Lecce 2014, p. 65. Vedi anche Archivio de «Il Ribelle», giornale clandestino, consultabile on line http://www.il-ribelle.it/, si vedano in particolare i numeri 13/14 riguardanti la Val d’Ossola.