First attempt of the magnicide

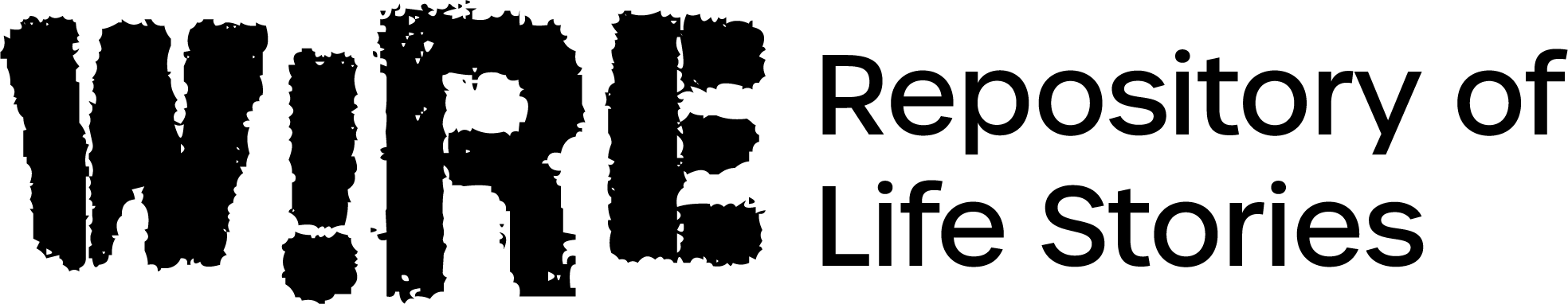

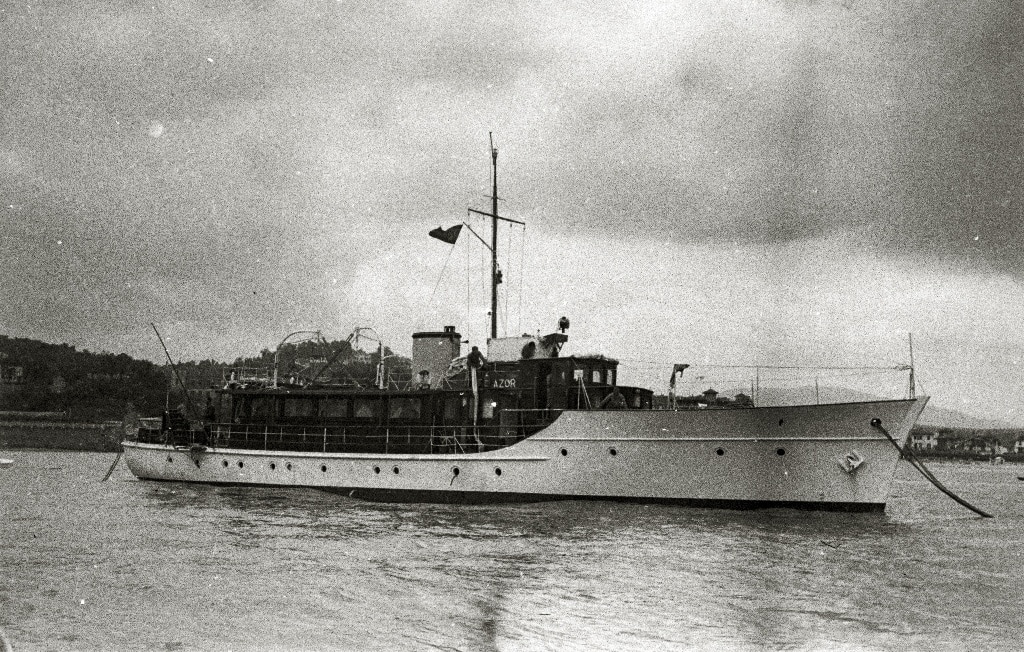

As for her involvement in the fight against Franco, she liaised with Home affairs on various missions in Spain. In 1948, together with a group led by Laureano Cerrada, she took part in an attempted anarchist-led attack to kill the dictator. Their plan was to bomb Franco’s yacht, the Astor, from the air using a plane bought in France.

Laureano realised that it would not be easy to attack their target on the road or to mine El Pardo. Any of these projects would have required a great deal of preparation, money and manpower, none of which they had. Moreover, Franco was under tight surveillance and it was impossible to get to him. The only way that occurred to them to overcome these obstacles was to attack from the only place that was unprotected: the air.

Franco was in San Sebastian, where we had gone to attend the second day of the regatta. Thousands of people gathered around La Concha beach, eager not to miss the show. The anarchists had been planning the magnicide for months. Their cover was a travel agency that had been created especially for that purpose under the name Empresa de Transportes de Galícia. It was supposed to operate as a transport company and it even managed to make some profits.

Cerrada found an aircraft dealer in Paris and he bought the Nord 1202-Norécrin II aircraft, with a maximum speed of 280 kilometres per hour. On one of the trips that the company organised to San Sebastián, Cerrada’s henchmen took a close look at La Concha beach and drew a plan of the outworks. Although the police ended up dissolving the company for suspicious activities, the mission to kill the dictator was not aborted. Nevertheless, when the day of the attack came, all their meticulous preparation was to no avail. They came within a hair’s breadth of exploding the device and bombing the Astor with incendiary bombs and shrapnel. What happened was that, at the last moment, the anarchists were surprised by military aircraft from the Air Force which made them desist.