Days of romantic communism

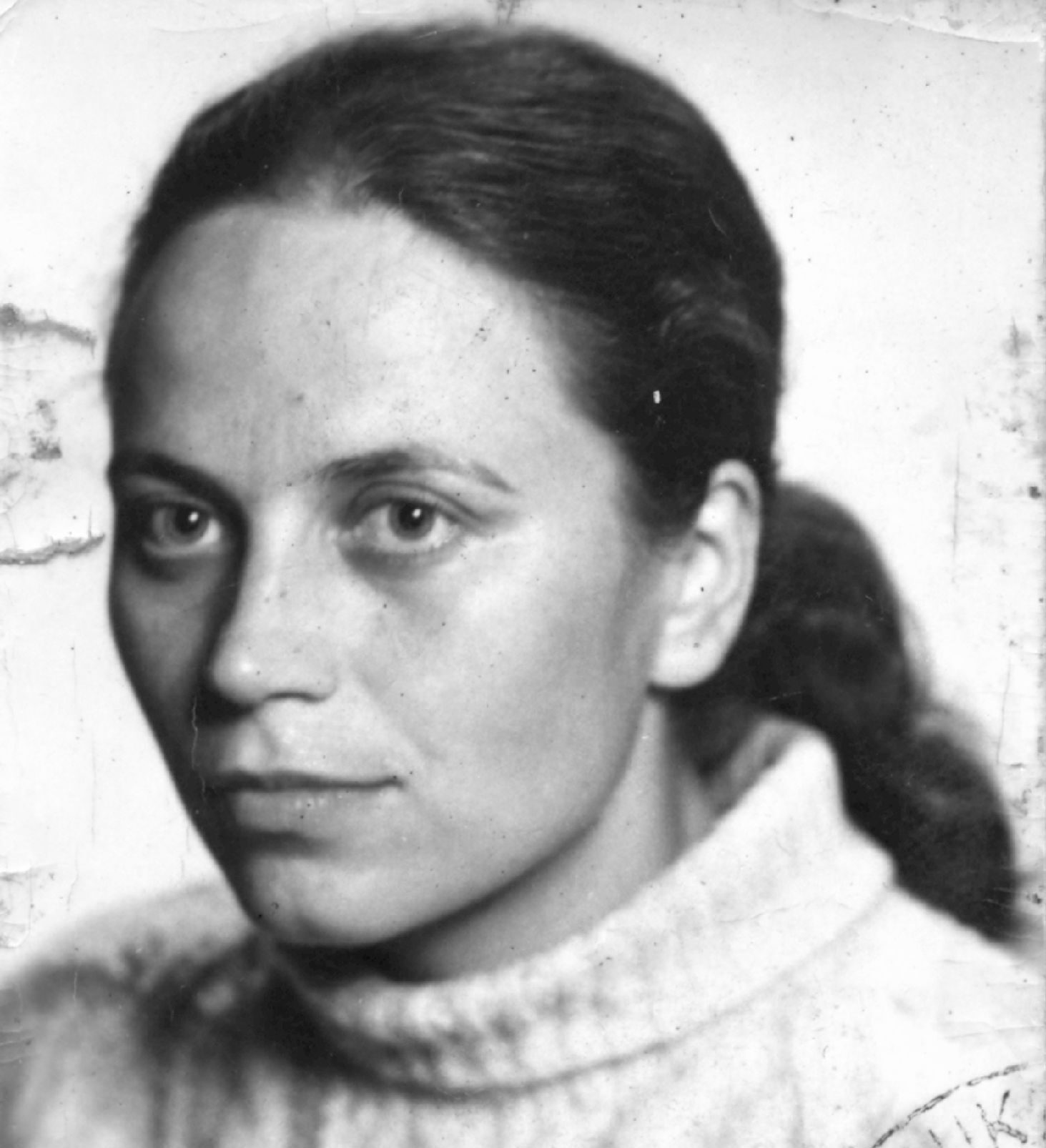

Joanna Duda-Gwiazda was born on 11 October 1939 in Krzemieniec (present-day Ukraine). During World War II, she and her family twice avoided deportation to the East.[1] The second time, her family was saved by railway workers. According to Joanna, that experience significantly influenced her attitude towards working people and her appreciation of their role, solidarity, and commitment, especially in situations that are dangerous and require great responsibility.

Joanna graduated from the secondary school in Nowy Sącz, and then from the Faculty of Ship Building in Gdańsk, where she majored in ship machinery and engine rooms. “I wanted to construct ships, it’s obvious”, she answered when asked about her choice of engineer as a profession. “These were the days of romantic communism, and the idea that you suddenly go to huge construction sites I regarded as its positive aspect. Though I did find my life during studies to be hard, due to the significant distance from home [in Nowy Sącz].”[2] In 1962, while still at the university, she married Andrzej Gwiazda. They were brought together by their passion for the mountains. They went not only to the Tatra Mountains, but also to Romania, Bulgaria, and even Spain (until 1976, when their passports were taken away from them). As Joanna recalled years later: “None [of our colleagues from the university] had enough strength [for the mountains], and then I met Andrzej, who thought nothing of that.”[3]

Becoming a dissident

The events of March 1968 in Gdańsk and the massacre on the Coast nearly three years later were very important experiences that shaped Joanna Gwiazda as a dissident and, importantly, as a determined opponent of the communist system. Joanna did not actively participate in those events, but she closely observed them, noticing the brutality directed against the protesters by the Citizens’ Militia and the army, and she became increasingly critical towards the policy of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR). At that time, her distinctive and independent ideas were forged, among which her particular sensitivity to the social problems of her compatriots was clearly visible.[2]

“Couple of the opposition”

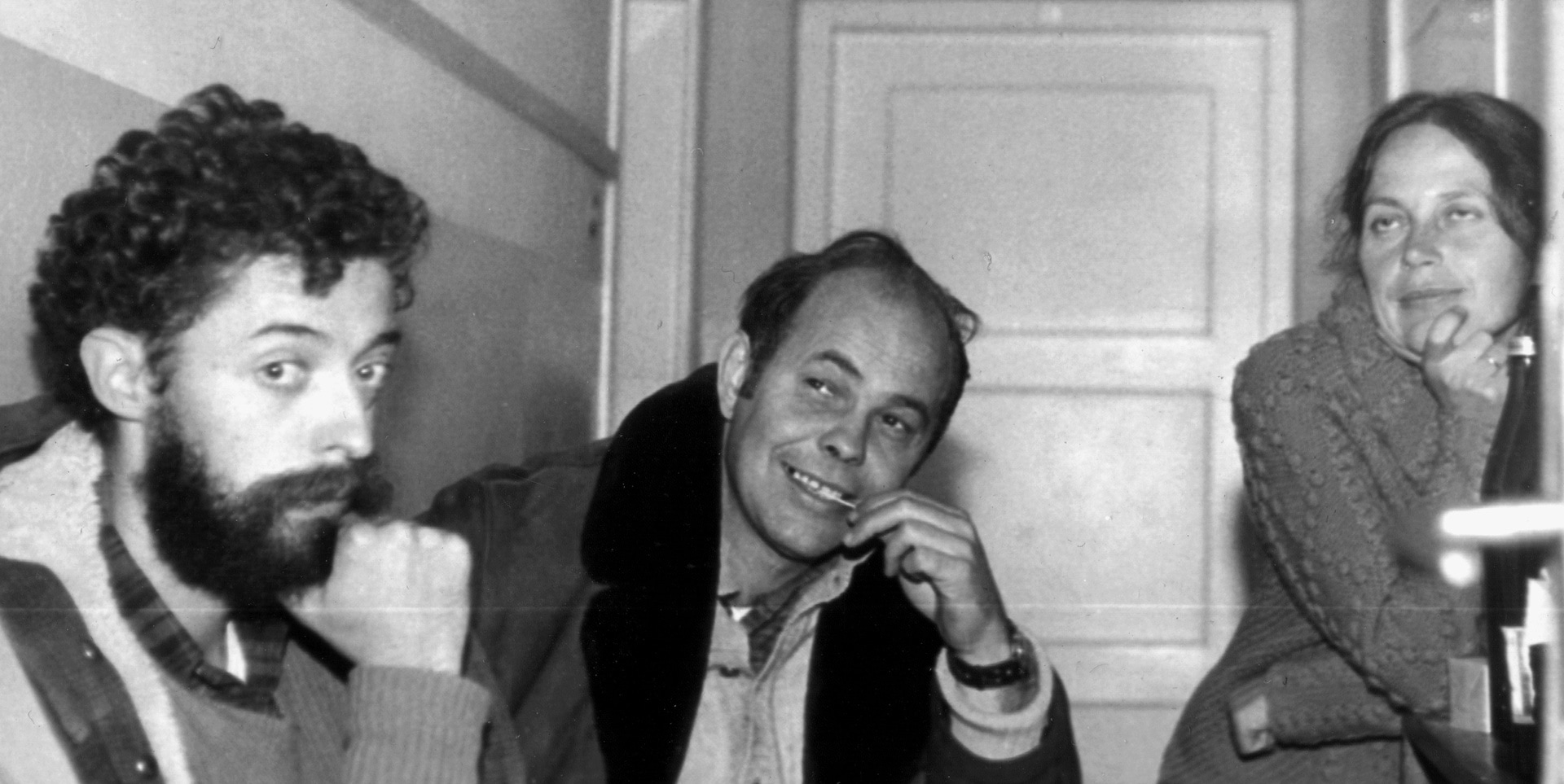

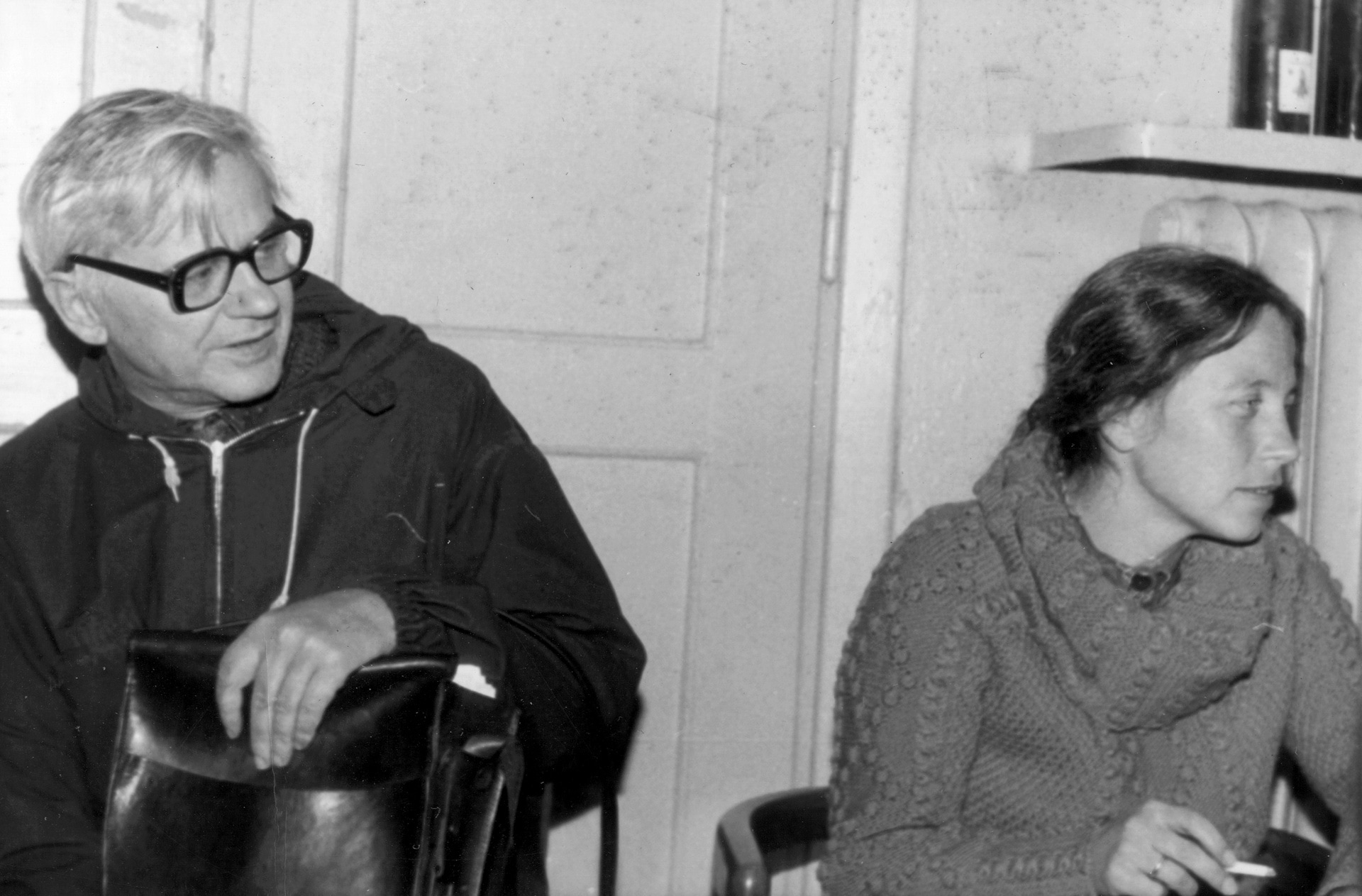

The Gwiazdas belong to the phenomenon of “couples of the opposition”, similar to, for example, Zofia and Zbigniew Romaszewski or Ludwika and Henryk Wujec.[3] She worked as a chief technologist at the shipyard in Gdańsk until 1965, then at the Central Office of Ship Constructions until 1971, and finally, until her retirement in 1999, at the Maritime Advanced Research Centre at the shipyard in Gdańsk.[4]

The Free Trade Unions of the Coast (WZZ)

In 1976, together with her husband, she wrote the “Letter to the PRL Sejm supporting the activities of the Workers’ Defence Committee”, the establishment of which they had learnt about from Radio Free Europe. At the same time, the Gwiazdas were deeply convinced that the opposition should focus their activities on the difficult situation of people working in the industry, especially under the piecework system, which they perceived as slave labour. Together they were searching for a formula that would enable them to conduct activities supporting a change in the labour system.[5] From that attitude arose the idea of the Free Trade Unions of the Coast (WZZ), established by Andrzej Gwiazda together with Antoni Sokołowski and Krzysztof Wyszkowski in April 1978. The WZZ Declaration was a call for democracy and the freedom to establish grass-roots social organisations in the PRL. Joanna and other activists helped the workers – in particular, she ensured that there were no legal grounds for the dismissals with which they were threatened (e.g. for being late or under the influence of alcohol). She taught union members how to handle problems on their own by drawing up applications, leaflets, and letters in defence of other workers. Furthermore, she also became involved in protests outside the Coast region. For example, in October 1979 she participated in the hunger strike at the Church of the Holy Cross in Warsaw to manifest solidarity with activists of the Czechoslovakian Charter 77.

In August 1980, as a member of WZZ, she participated in the strike at the Gdańsk Shipyard. She was also a member of the Praesidium of the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee and contributed to the creation of the 21 demands of the strikers. In her opinion, the demand to undertake economic reform was the most important one. She was deeply interested in the report about the state of the country and in negotiating a way to end the downturn.

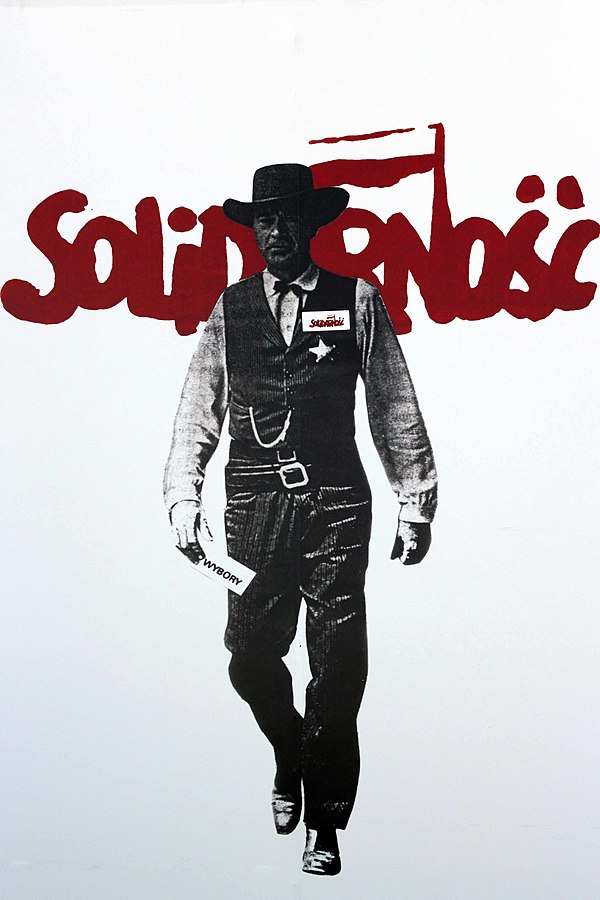

The Independent Self-Governing Trade Union “Solidarność”

After the signing of the August Agreement, Joanna focused on developing the structures of the legal “Solidarność”[6]: “The extent of the work that needed to be done simply exceeded our strength, resources, and available time, because apart from organising the union, there were plenty of other problems with which people came to us, frequently private ones; and one did [not] know what to do with all of this, because now everybody wanted the union to help them.”[7]

While Andrzej travelled around the country, Joanna organised meetings of the top management in Gdańsk, prepared documentation, and handled propaganda.[8] Until 29 September 1981 she was a member of the regional management and its press representative. In the union, she represented the group of the so-called “hard line” towards the authorities, and this brought her and Anna Walentynowicz together. Along with her husband, she was under the constant surveillance of the security services, and this meant, for example, that their flat was bugged.

When martial law was introduced in December 1981, Joanna was interned (as was Andrzej) and retained in internment facilities for women (in order) at Gdańsk, Bydgoszcz, Gołdap, and Darłówko. She was released on 22 July 1982.[9]

Propaganda activities

In 1988 she went with her husband for several months to the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, and France, where they informed the public opinion about the situation in Poland.

In 1989 Joanna and Andrzej Gwiazda strongly opposed the Round Table Talks, believing that the agreement contradicted the previous activities of “Solidarność”. They were also strong opponents of the economic reforms of the 1990s, interpreting them as having ruined the previous achievements of the country and disregarding the opinions of workers. At that time, their efforts were frequently rejected or ignored.

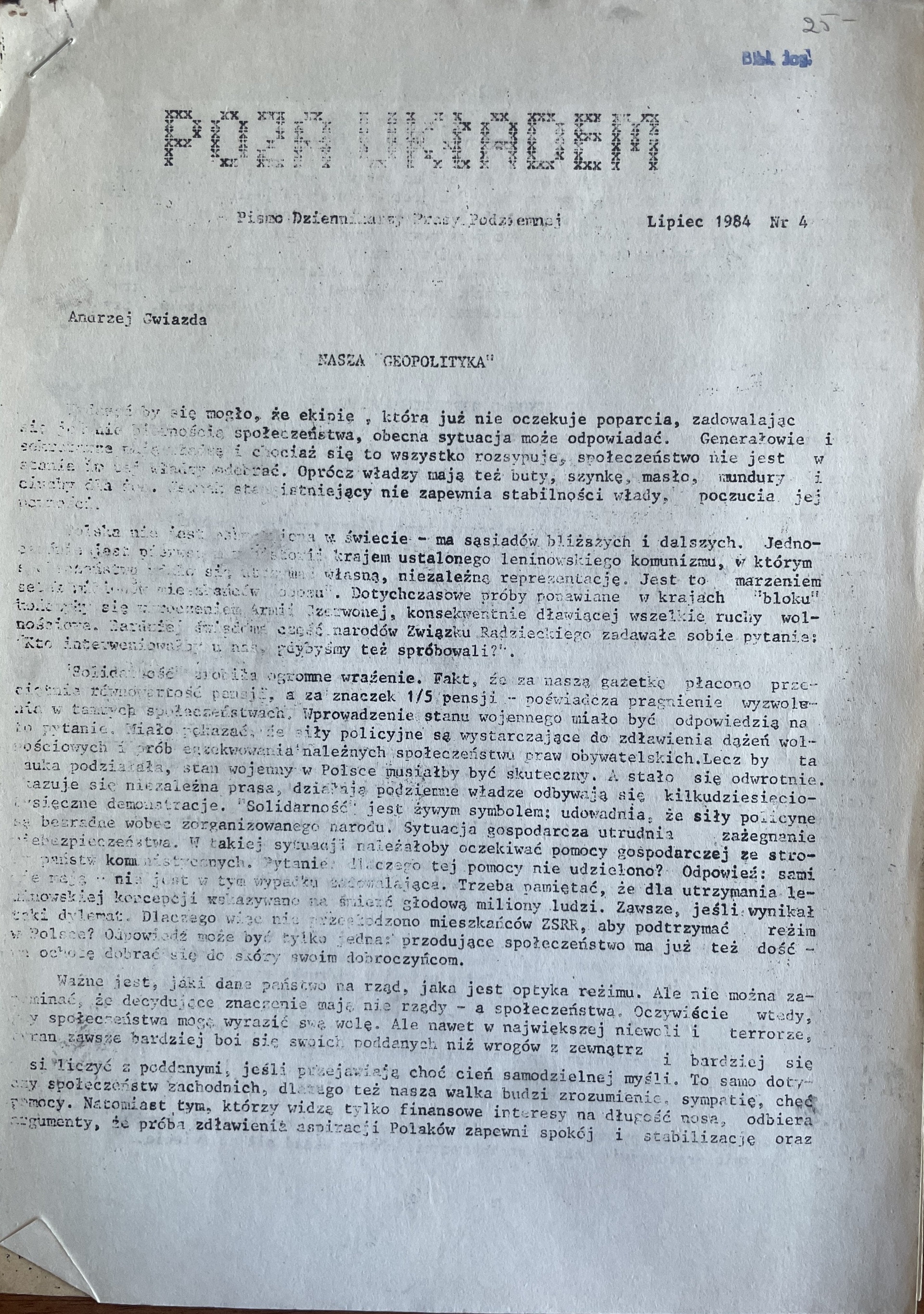

For many years, Joanna was an editor of magazines associated with Free Trade Unions, “Solidarność”, or independent unions. Such publications included Robotnik Wybrzeża, the weekly Solidarność, and the underground paper Skorpion, as well as Poza Układem, Obywatel (after her retirement in 2000), and Nowy Obywatel (presently). Joanna is also the author of numerous essays and a book about mountain climbing entitled Polska wyprawa na księżyc.[10]

After 1989 she became involved in activities aimed at commemorating the heroes of “Solidarność”. She is still an active campaigner – since 2011 she has been working on the board of the “Solidarni 2010” association. She also promotes environmental protection in Poland. To this day she lives in Gdańsk with her husband.

Sources

- https://gdansk.gedanopedia.pl/gdansk/?title=DUDA-GWIAZDA_JOANNA,_in%C5%BCynier,_dzia%C5%82aczka_opozycji_demokratycznej.

- https://encysol.pl/es/encyklopedia/biogramy/15678,Duda-Gwiazda-Joanna.html?search=62981444685685

- https://wzz.ipn.gov.pl/wzz/biogramy/2290,Joanna-Duda-Gwiazda.html

- Opozycja w PRL. Słownik biograficzny 1956–89. Vol. 3.

- Penn S., Sekret „Solidarności”: kobiety, które pokonały komunizm w Polsce, Warszawa 2014.

- Duda-Gwiazda Joanna. Relacja

- https://opowiedziane.ipn.gov.pl/ahm/notacje/24257,Duda-Gwiazda-Joanna.html

- Z Gwiazdami. Podróż bez końca – filmy dokumentalne.

- https://vod.tvp.pl/filmy-dokumentalne,163/z-gwiazdami-podroz-bez-konca,336117

Written by Weronika Bojęś