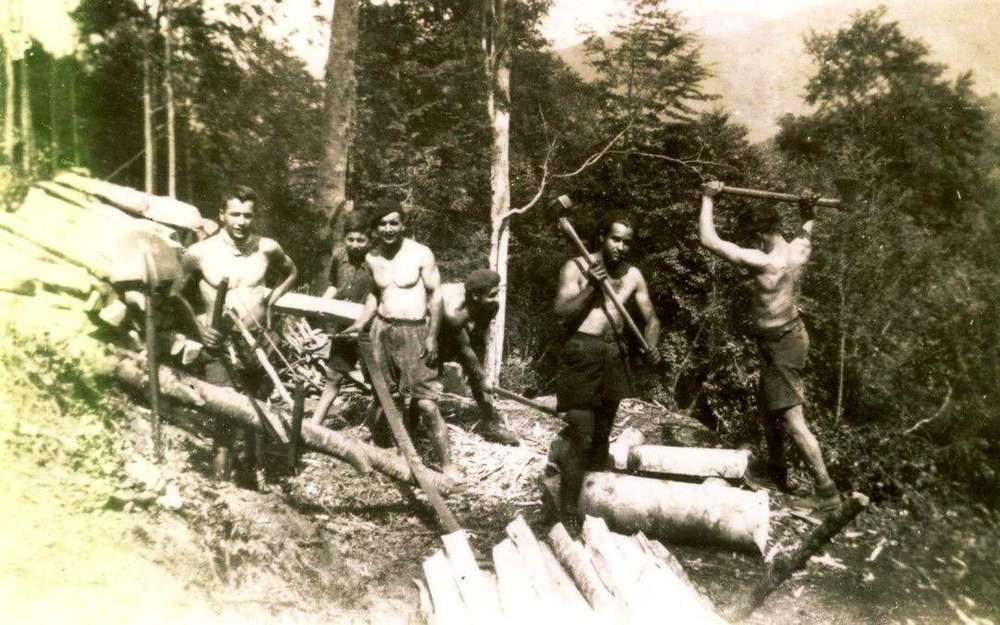

Hermínia, who was 17 years old at the time, would make herself useful by helping, like many other women in the Resistance, to provide food, medicines, supplies, clothing and information, as well as moving packages and weapons between the different points of support, such as the chantiers, for example. Without these support tasks, it was quite impossible for the Maquis to survive in such adverse conditions, especially with Pétain, the German and Gestapo militia chasing them. The 14th Guerrilla Brigade of the Ariège recruited her into the 3rd Brigade to act as a liaison between its three battalions and as a courier between the other brigades of Haute-Garonne, Aude and Pyrénées-Orientales. She would say of herself: “I became a little soldier, available 24 hours a day”. The 3rd Brigade from 14th July 1943 until 11th November 1943, was responsible for 40 sabotage attacks on the railway lines, 60 on the high voltage lines and for the paralysis of industrial production in the areas of Pamiers and Tarasco. On 1st May 1944 the aluminium factory of this town was sabotaged, and four days later, the attack was repeated.

These were all very dangerous tasks, especially due to the strict German control and the extension of the area, and Hermínia had to travel up to 80 km by bicycle or train to transport weapons. She was also supposed to take people from train stations to safe points. All these women were extraordinarily brave and courageous. They travelled the whole of the Ariège by bicycle with messages hidden in their saddles or in their handlebar tubes. Despite the danger, they never hesitated in their mission. In her own words: “Séraphine and I cycled there and back on the same day because we also liaised with the guerrilla group in Toulouse. The papers were normally hidden in the handlebars.”

In 1944, she even transported two dismounted machine guns from Toulouse to Verniolle, each in a cardboard suitcase. “On that day, it was raining heavily, the cardboard was wet and the suitcases yawned, exposing their contents. There was no one at Varilhes station to meet with the Maquis, who were due to arrive but had been blocked by a landslide on the road. So, we hid the suitcases in the bushes.”

In addition, she would go to pick up young men who wanted to join the fight and she had to guide them with very specific codewords in order not to be exposed. She recalls that, on one occasion, her companions suspected that the meeting with one of the young men was being watched by the Germans. They warned her and she decided to proceed regardless, knowing that there was a risk of being arrested –with everything that was involved– or killed by her own companions, who were watching them from a distance with grenades in case they were caught. If that happened, their order was to finish them all off, including her. “Two guerrillas were hiding in a bush at some distance from us. In case the Germans caught me, their job was to throw grenades to kill them, and me with them, to avoid torture so that I couldn’t talk”.