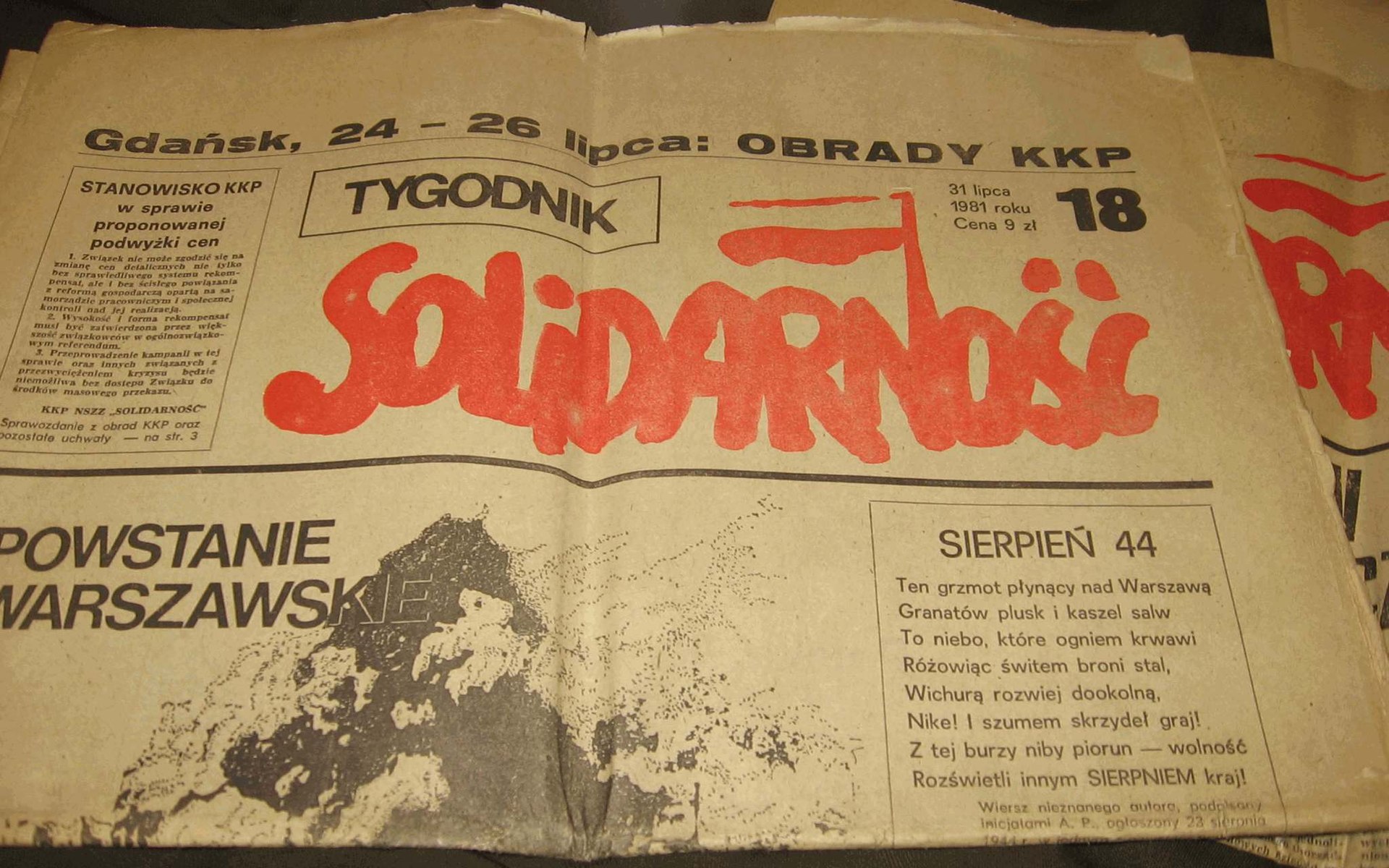

On 16 December 1981 Helena, Joanna Szczęsna, Zofia Bydlińska-Czernuszczyk, Anna Bikont, Anna Dodziuk, Katarzyna Harpińska, and Małgorzata Pawlicka began publishing Informacja Solidarności (“Information from Solidarność”), a zine that was a few pages long and initially issued daily. In February of the following year, the editing board began publishing the Tygodnik Mazowsze (“Masovia Weekly”), which over time became the most prominent magazine of Solidarność.

Its inception is linked with the tragic story of Jerzy Zieleński, a former member of the Home Army, prisoner of Pawiak, and participant of the Warsaw Uprising who was appointed as editor-in-chief of the new magazine Mazowsze just before the imposition of martial law. He got to work, created the editorial team, and made arrangements with authors. However, upon learning about the imposition of martial law, he committed suicide on 13 December 1981. The editorial team remembered Zieleński by publishing the magazine’s first issue on 11 February 1982 as issue No. 2. The first issue was symbolically dedicated to the late editor.

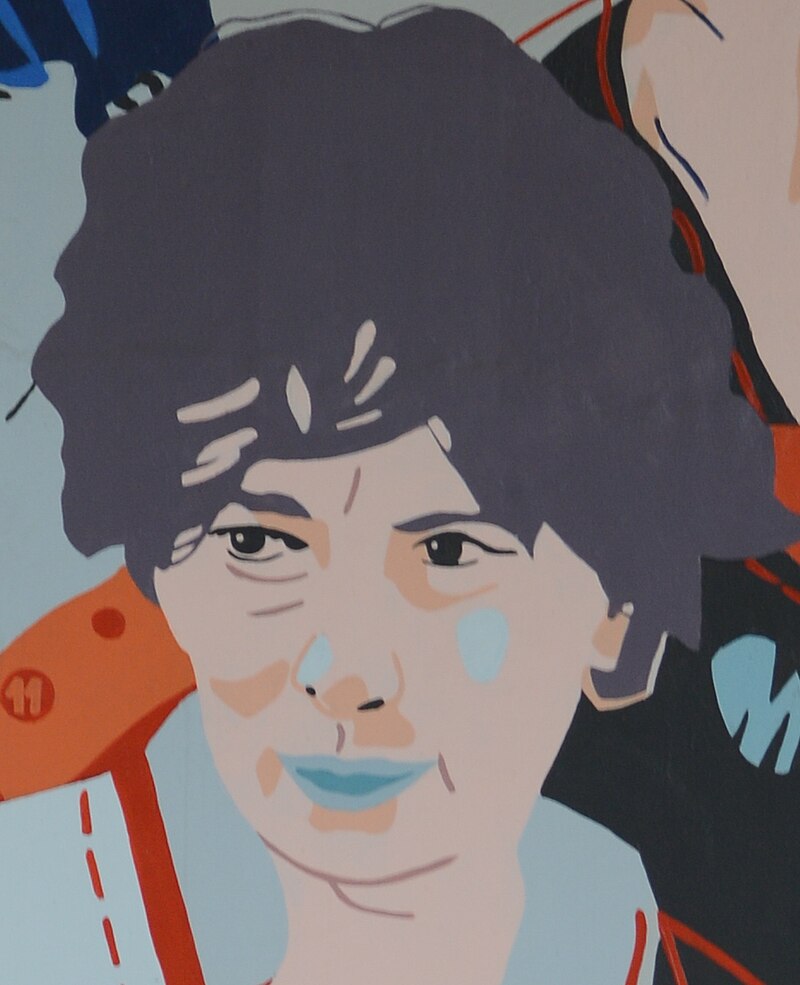

After Zieleński’s passing, Helena Łuczywo took over the post of editor-in-chief and began working with the female-dominated editorial team. She maintained close relations with Zbigniew Bujak and other leaders of Solidarność who remained in hiding. Helena helped with the living arrangements of the underground state and searched for suitable flats.

The editors of the magazine, which was to become a press body for regional authorities of the opposition, worked on the go, moving the editorial office every two weeks to a new flat to avoid being discovered. The editorial team also included Anna Dodziuk, Marta Woydt, Wojciech Kamiński, and Ewa Kulik, who was the crucial link between the magazine and the regional authorities of the underground Solidarność. Due to the mass detainment of men, who until then usually held key organizational positions, the underground press became the most female-dominated area of the Polish democratic opposition. Marianna Domańska, whose flat served as a meeting place for the editorial team, also cooperated closely with Tygodnik. 290 issues were published by April 1989, which puts it at the absolute forefront of underground magazines. Regular publishing was possible thanks to an extended network of printers, editors, and distributors.