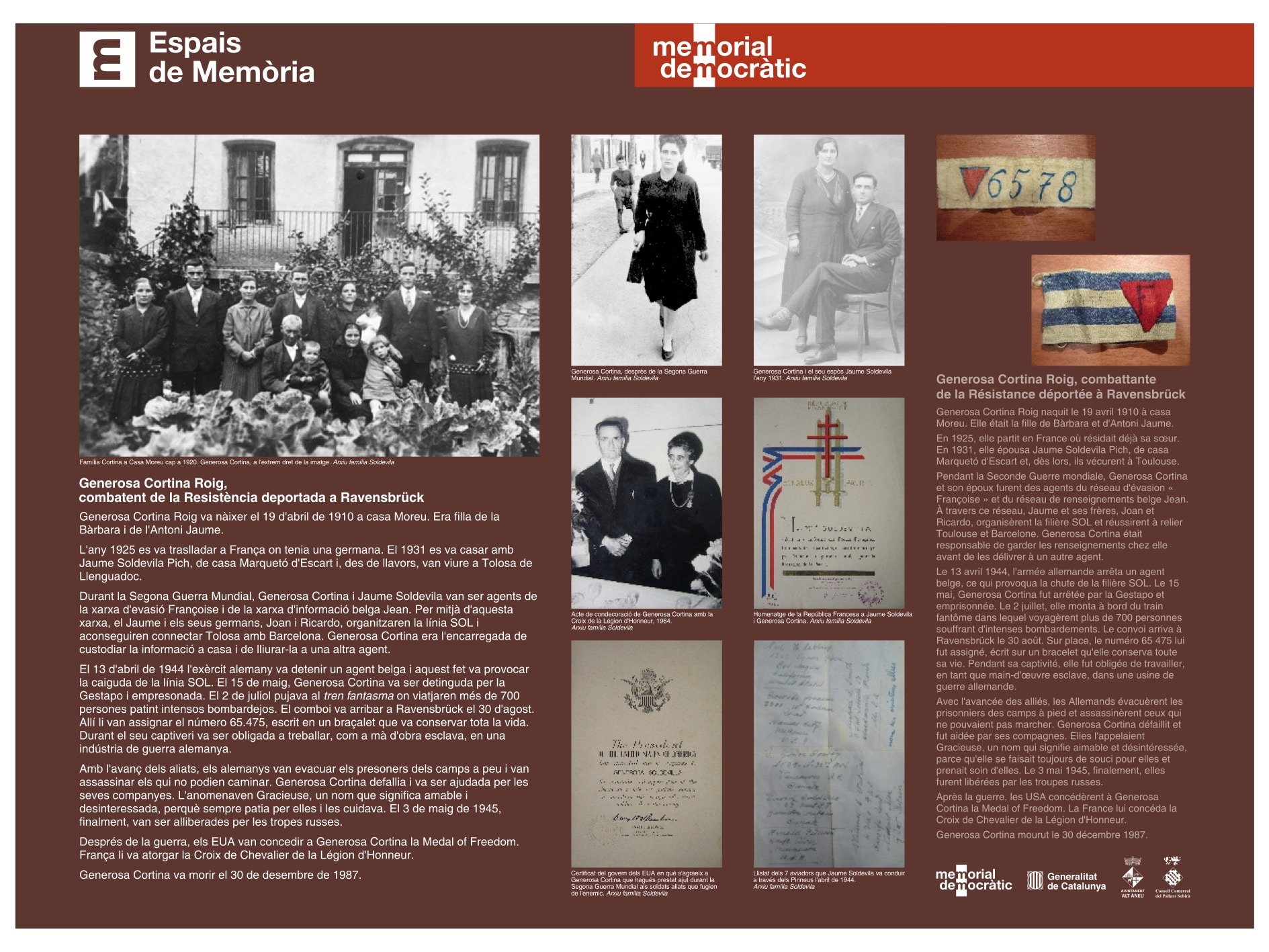

On 26 August 1944 they finally entered Germany, and five days later, France was liberated. On 28 August 28 1944 they arrived at Dachau, where Generosa was registered in the camp with serial number 93.882. The women aboard the train were the only women coded and registered in Dachau, because the Nazi commanders did not know whether they would end up being transferred to Ravensbrück. A week later they set off again and finally, on 9 September 1944, they were interned in Ravensbrück, in Barracks 22. There, Generosa was registered again, this time with serial number 65,475, written on a bracelet that she kept all her life.

During her captivity, she was forced to work as slave labour in a German war factory. More specifically a kommando in Oberschöneweide, a suburb in Berlin, where they were forced to work day and night with other women. She shared the kommando with the Beleta women, Elvira, Maria and Conxita. They were in charge of manufacturing and inspecting aviation material at the Henkel factory, but as Conxita explained, they used any opportunity to sabotage it: “I was supposed to control the parts, but we sabotaged them. We all did it. I was caned a lot and they shaved my head. Out of 650 women, at the end there were only 115 of us left”.

When the factory was bombed, 80% of the kommando died and they took the opportunity to escape. It was a brief moment of freedom, but soon the SS got hold of them again, and as the barracks were destroyed, they were locked up for three days. All the survivors were kept in a filthy cellar, without light or ventilation and with water dripping from the walls, from where they could only get out for a few minutes a day. Then on 14 April, they were transferred to the Köpernick kommando, where they worked digging trenches in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, a mixed camp where the former president of the Spanish Council of Ministers, Francisco Largo Caballero, had been imprisoned.

Between 19 and 21 April 1945, as the Allied troops approached, the SS began one of the so-called death marches, in which any prisoner who could not keep up the pace was killed on the spot. Generosa was one of the weak prisoners who were unable to keep up with the march, but thanks to the support of two other Spanish women, she was able to survive the long walk.