Mistakenly believing the Allies’ arrival in the capital to be near, Pietro Nenni gave orders immediately after the Anzio Allies’ landing to free Sandro Pertini, Giuseppe Saragat, Luigi Andreoni, Carlo Bracco, a Trastevere partisan, Torquato Lunadei, Ulisse Ducci, and Luigi Allori from Regina Coeli Prison[13].

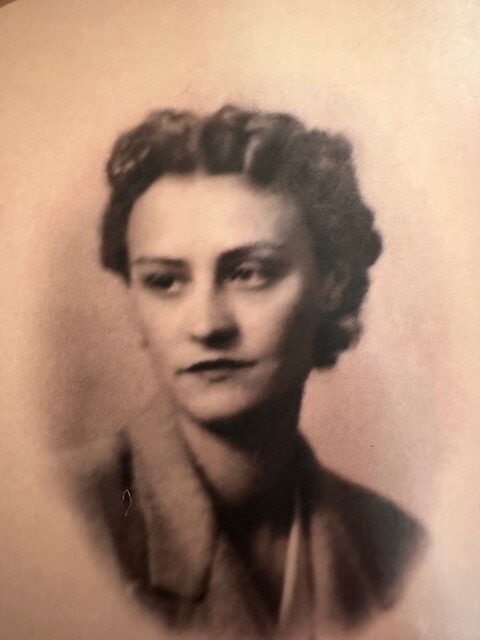

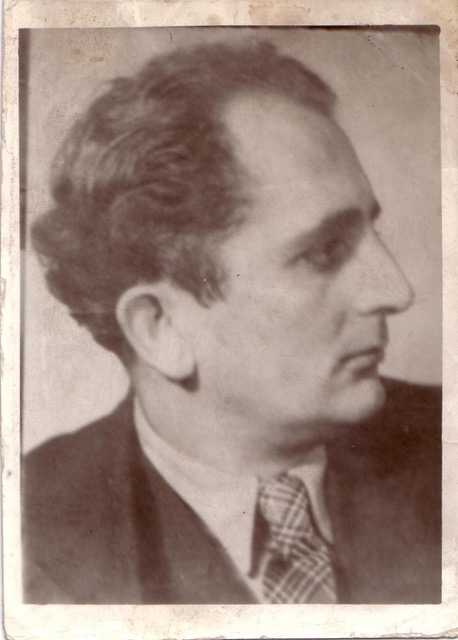

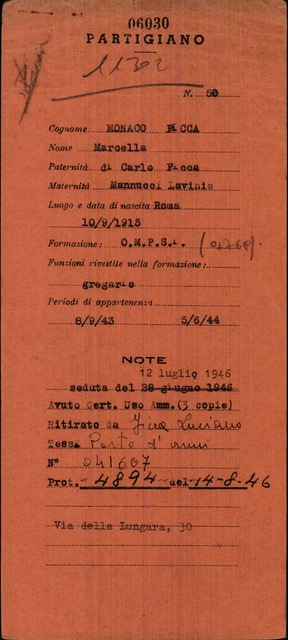

These detainees were first locked up in the third wing of the prison, which was exclusively German, and to which Alfredo Monaco had no access. It was thanks to the interest of Giuliano Vassalli and Massimo Severo Giannini, both lawyers, that they were moved to the sixth wing, under Italian jurisdiction, so that Monaco could tell them about the plan and warn them of the moves of his comrades. Vassalli and Giannini had until September 8 been officers at the military tribunal in Rome and had procured stamps and release forms. Marcella Ficca, finally, had been in charge of filling out these forms, thanks to her friendship with Carretta, and because of finding a secret place where the escapees would be hidden if the coup was successful.

Collaborating with her was Filippo Lupis, a young lawyer who, because of his profession, could circulate around the prison undisturbed. Vito Maiorca, a socialist militant, was a lieutenant at the office of the Police of Italian Africa (PAI) where the prisoners were to pass when they were released. Alfredo Monaco, the prison doctor, could control any movement within the penitentiary and arranged to warn Pertini to fake an appendicitis attack on the evening of January 23 so that as a doctor he could inform him of developments in the operation[14].

On Jan. 24, 1944, the plan was put into action; however, it had not been calculated that political prisoners, had first to go to the Police Headquarters before being released: it was the prison director, Donato Carretta, already in agreement with Marcella, who suggested that they make a phone call on behalf of the Police Headquarters to allow their release. However, that very afternoon the outside phone lines were down. Until five o’clock in the afternoon, the plan seemed to be blown up until Marcella came up with the idea of going to her brother Luciano, who had infiltrated the PAI in Piazza dell’Arco di San Callisto in Trastevere. It was from that barracks, with internal telephone lines, that Filippo Lupis, pretended to be a police officer and phoned Regina Coeli, ordering the immediate release of the prisoners[15][16].

The prisoners were asked by German officers to pack up their stuff, but one of the seven men claimed the gold cufflinks that had been confiscated from him: it was Pertini who made it clear to his friend that this was an escape and not a regular release[17].

When they were finally freed they were hidden in the Monacos’ apartment and later moved by Luciano Ficca to the apartment in the PAI barracks in Trastevere, belonging to a marshal who was on leave[18]. On January 28, the voice of Paolo Treves announced during the broadcast “The Voice of Italy”: “This is Radio London. An Italian patriot has helped to escape Pertini and Saragat, top leaders of the Italian Socialist Party and leaders of the Italian Resistance, from prison. Tonight the usual column will not take place because our hearts are moved by the escape from Regina Coeli of Sandro Pertini and Giuseppe Saragat who were sentenced to death by the German war tribunal. Our two comrades have resumed their place of struggle in Rome”[19].

[13] Vico Faggi (a cura di),

Sandro Pertini. Sei Condanne, due evasioni, Mondadori, Milano 1974, pp. 346-347.

[9] Cesare De Simone,

Roma città prigioniera, i 271 giorni dell’occupazione nazista (8 settembre-giugno 1944), Mursia, Milano 1994, pp. 66-69. See also:

Guiseppe Saragat e Sandro Pertini – La fuga dal carcere di Regina Coeli

[14]Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Ministero della Difesa, Fondo RICOMPART, Commissione Lazio, b. 223 PSIUP, fasc. IV zona, Attività militare del Centro, s.d. ma post-liberazione

[15]Cesare De Simone, Roma città prigioniera, i 271 giorni dell’occupazione nazista (8 settembre-giugno 1944), Mursia, Milano 1994, pp. 66-69.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_6BE1UlWMPE (qualità più bassa ma è lo stesso)

[16]Davide Conti (a cura di), Le brigate Matteotti a Roma e nel Lazio, Odradek, Roma 2006, pp. 47-48.

[17] Vico Faggi (a cura di), Sandro Pertini. Sei Condanne, due evasioni, Mondadori, Milano 1974, p. 347.

[18] Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Ministero della Difesa, Fondo RICOMPART, Commissione Lazio, b. 223 PSIUP, fasc. IV zona, Attività militare del Centro, s.d. ma post-liberazione.

[19] Andrea Ricciardi, Paolo Treves. Biografia di un socialista diffidente, Franco Angeli, Milano 2019.