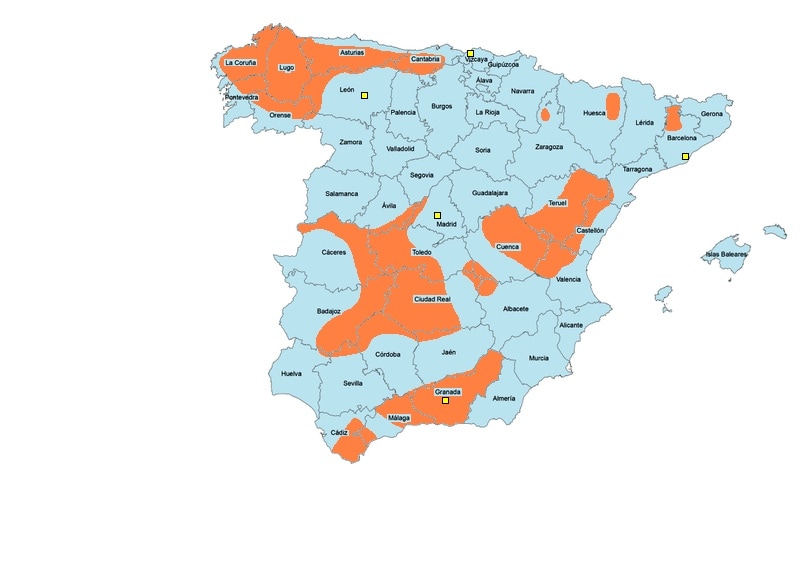

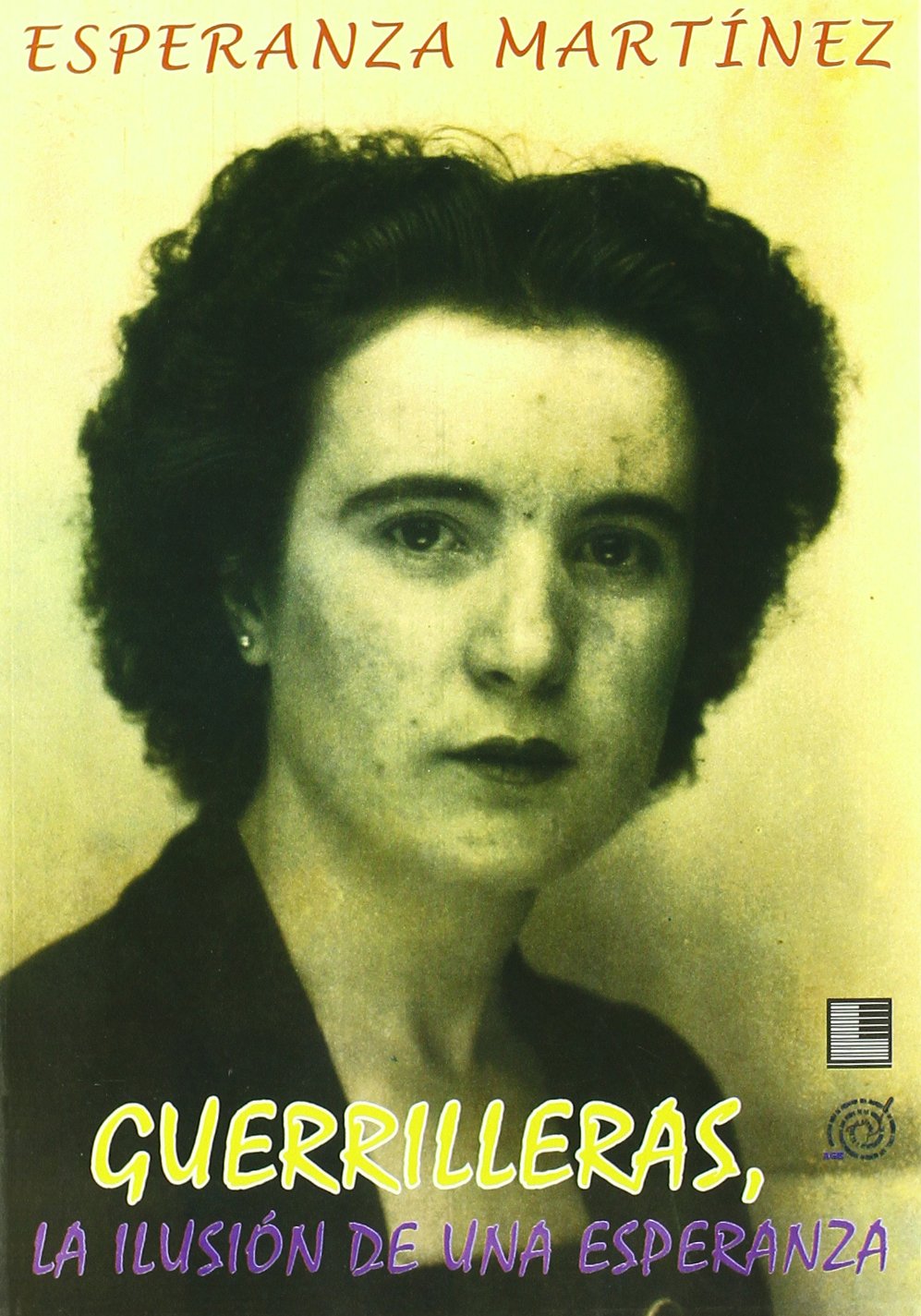

Esperanza refers to those years as extremely hard times due to the living conditions and the persecution. This is how she recounts them: “Those times were extremely hard […] No matter what people may say, the mountains cannot be portrayed. We would go from one place to another and, when we least expected it, the camp was attacked and we had to flee the persecution rushing for cover and hiding in the pine trees. It was terrible.” From 1949 onwards, “It was all about resistance. At other times it had been about keeping active, going to the villages, campaigning here and there, and there was a lot of guerrilla activity, but at that time, in 1949, it was more about guerrilla evacuation, and if by chance there was an attack on the camp that caught us unawares, we could only give a defensive response, but we could not attack, we could never fight back. Although that happened only that year. Before, we could fight back, but not then. I once found myself in the middle of an attack on the camp we were staying in and there was a lot of shooting and a lot of things happened. A couple of the Guardia Civil accidentally ran into the camp and everyone started shooting at each other… One of us got wounded and some of them got wounded too, and one was also killed, a death which they later charged us with in our criminal record. Half an hour later the place was packed with Guardia Civil officers… Then we took refuge in a thicket –under the sun, because it was June or July; nobody could imagine that we were in the thicket, it wasn’t a bush or anything–, until night came and, after communicating with the guerrillas, we regrouped at an assembly point. There was always an assembly point so that, if something happened, we could meet there… It was quite complicated, you know…”

Reme talks in her biography about the way she dealt with the guerrilla men: “Our life in the mountains was the same as theirs, the rucksack always on our backs and the weapon ready in case we needed it. Fortunately, we never had to use it. We were not treated differently or discriminated against for being women. We had good teachers and we gave classes on cultural training, politics and anything else that could cultivate us more and better.”

The guerrilla women were in charge of providing the information, supply and care needed for the survival of the resistors, and at the same time they received training. “Our life consisted mainly in reading, studying, participating in meetings and political discussions, and informing ourselves about the situation whenever we could get some information through the radio, because there was a lot of interference…. But in all of that, and the points of support people used to supply the guerrillas, women never went anywhere to supply. The Guardia Civil was not supposed to know where we were, so we didn’t go anywhere to supply, but the men did it, and through the points we always received news and information that was later discussed in the camps. It was difficult, it was complicated: sometimes there was food, sometimes there wasn’t. You had to live in the pine trees, in the forests, only like that”.