Bibliography

Cabrero, Claudia. Mujeres contra el franquismo (Asturias 1937-1952). Vida cotidiana, represión y resistencia, Oviedo, Ediciones KRK, 2006.

Creus, Jordi. Dones contra Franco, Badalona, Ara Llibres Edicions, 2007, pp. 149-174.

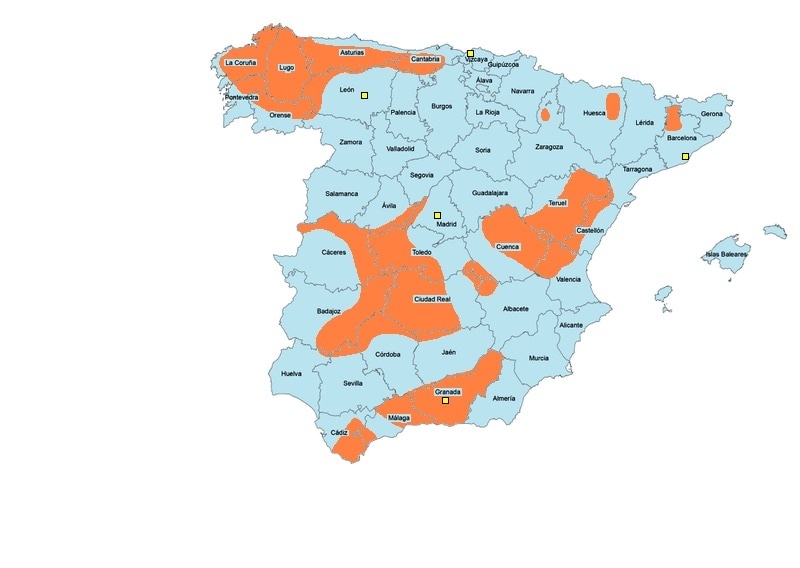

Martínez, Odette. “Los testimonios de las mujeres de la guerrilla antifranquista de León-Galicia (1939-1951)”, in Julio Aróstegui and Jorge Marco (eds.): El último frente. La resistencia armada antifranquista en España 1939-1952, Madrid, Los Libros de la Catarata Editorial, 2008, pp. 313-328.

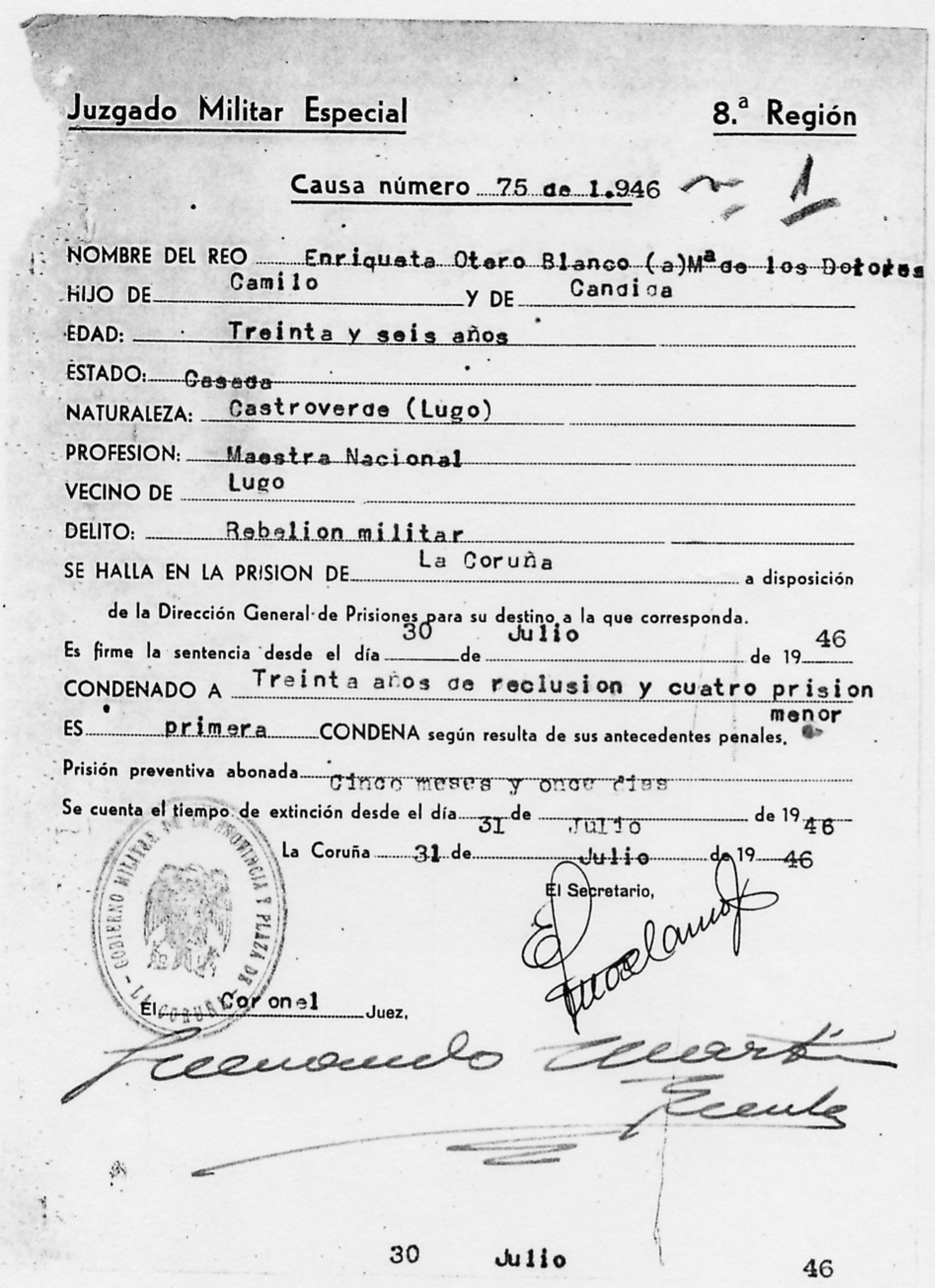

Rodríguez, Ángel. As vidas de Enriqueta Otero Blanco. Lugo, Fundación 10 de Marzo, Colección Estudios Nº 3, 2002.

Romeu, Fernanda. El silencio roto. Mujeres contra el franquismo, Barcelona, El Viejo Topo, 2002.

Romeu, Fernanda. Más allá de la utopía: Agrupación Guerrillera de Levante, Ciudad Real.

Yusta, Mercedes; Peiró, Ignacio. Heterodoxas, guerrilleras y ciudadanas. Resistencias femeninas en la España moderna y contemporánea, Zaragoza, Institución Fernando el Católico, 2015.

Yusta, Mercedes “Las mujeres en la resistencia antifranquista, un estado de la cuestión”, Arenal: Revista de historia de mujeres, 12:1 (2005), pp. 5-34.

Yusta, Mercedes “Hombres armados y mujeres invisibles. Género y sexualidad en la guerrilla antifranquista (1936-1952)”, Ayer, 110 (2018), pp. 285-310.

Audiovisual