In 1939, Elvira was practically alone. And in addition to that, she had to face 15,000 pesetas fine imposed on her father in accordance with the recently adopted Act of Political Responsibilities for sympathising with the Republic. And so Elvireta, who at that time was only 11 years old, had to go to the Civil Register in Tamarit to settle the matter. In order to have the fine cancelled, she engaged in a lengthy institutional claim in which she acted as a plaintiff although she was still a minor. The role played by the two officially accredited registering bodies, both on the part of the Town Council and on the part of the local parish, was particularly repressive. First, they refused to issue a death certificate for Elvireta’s father, and without the certificate she could not cancel her father’s debt and all his remaining assets were at risk. The village’s chaplain, Juan Fusté Vila, proposed as a solution to issue a death certificate stating that the death should be attributed to “natural causes” and that he had been found dead in his cell. This way, the debt could be cancelled. But although she was only 11, Elvireta refused to sign such a lie. Her father had not died, he had been beaten up to death. Elvireta refused to sign, claiming that she was still a minor. Finally, after a long and lengthy procedure and several interrogations at the Tamarit court, the penalty was cancelled and she was able to keep her father’s assets.

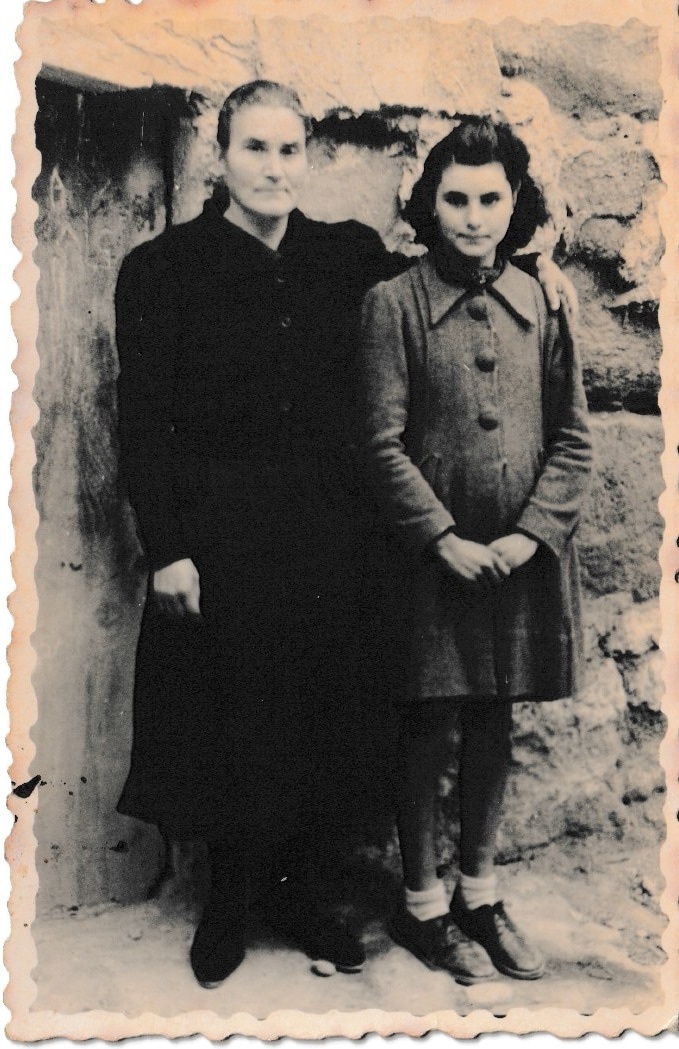

Elvireta had to leave school again in march 1942 after her mother became seriously ill. Severely weakened by her time in prison, she died of a stroke in 1942, a year after her release. Elvireta was barely 14 years old when she became an orphan. Overwhelmed by the pressure caused by the repression of the defeated, and unable to manage with her uncles their heavily taxed estate, she fought the authorities for a tax rebate.

At the age of 16, she decided to resume studying at the Dominiques of Lleida, where she stayed for two years. Since she was under strong surveillance and the regime knew she had relatives abroad, she had to set up a plan with the nuns, who certified that she was staying with them throughout the year so the authorities would let her go to Andorra to visit some friends. Once in Andorra, she crossed the border and was reunited with her brothers.

After that, she went back to Albelda and waited for her brothers to return. They returned after having asked for the pardon granted by Franco to the fugitives. Roque returned in 1947. Pilar also returned to divide the property equally among them, although she ended up going back to Paris to her family. Antonio, however, never wanted to return.