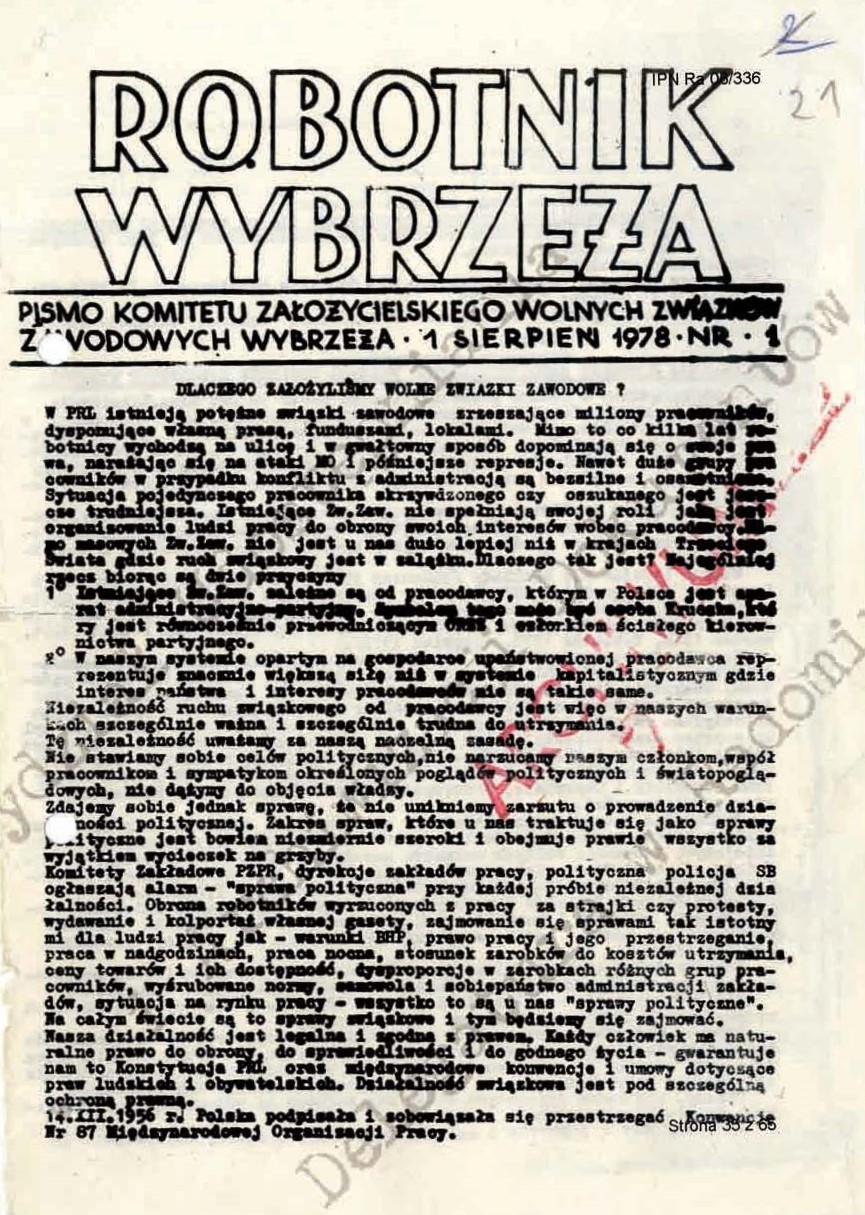

In the end, on 7 August 1980, as workers across the country began to protest in the wake of another political and economic crisis, Anna Walentynowicz was dismissed from the shipyard on disciplinary grounds.[1] The activists of WZZ Wybrzeże, led by Bogdan Borusewicz, saw this as a political opportunity to launch a mass protest. On 14 August 1980, a strike began at the shipyard that was to be decisive in the history of the Solidarity movement, and started with the demand for the reinstatement of Anna Walentynowicz. A leaflet that was printed illegally in 8,000 copies recalled the biography of the exemplary worker who had been awarded the Bronze, Silver and Gold Crosses of Merit, who had worked for independent trade unions, and who had been illegally dismissed from the shipyard after 30 years’ service, five years before her retirement: “If we cannot stand up to this, there will be no one to speak out against an increase in norms, violations of health and safety or mandatory overtime. It is therefore in our own interest to defend such people. That is why we are calling on you to speak out in defence of the crane worker Anna Walentynowicz. If you do not, many of you may find yourselves in a similar situation.”[2]

Under pressure from the strikers, led by Lech Wałęsa as chairman of the strike committee, the management backed down and Anna was reinstated two days later. On 14 August, Walentynowicz addressed a crowd of striking shipyard workers for the first time and also took part in negotiations with the shipyard management. On 16 August, the management finally agreed to wage rises, the construction of the December 1970 memorial and the reinstatement of dismissed workers.

Officially the strike was over, but the protests had already spread throughout the Tri-City, and representatives of the striking factories, many of them much smaller than the shipyard, called on the shipyard workers to support their demands. According to the official, largely mythologized narrative of August 1980, the Solidarity strike was saved by women: Anna Walentynowicz, Alina Pienkowska and Ewa Ossowska. They spoke to the shipyard workers at Gate 3, who were leaving the factory tired of the strike, and appealed to their consciences to support other factories. In practice, however, this was of little use. In fact, only a few hundred strikers remained in the shipyard on 16 August, but this in no way diminishes the role that Free Trade Unions women activists, including Anna Walentynowicz, played in August 1980. Although most shipyard workers went home that night, an Inter-Factory Strike Committee (MKS) was set up under the leadership of Lech Wałęsa. Walentynowicz represented the Gdansk Shipyard on the Presidium. She was also among those negotiating with the Church and party authorities to organize the first mass for the shipyard strikers.

[1].: Anna Walentynowicz, [in:] Encyklopedia Solidarności [Encyclopedia of Solidarity]. https://encysol.pl/es/encyklopedia/biogramy/19299,Walentynowicz-Anna.html [access on 27.07.2023]

[2] “Do pracowników Stoczni Gdańskiej” (“To the workers of the Gdańsk Shipyard”) leaflet, from the archives of Bogdan Borusewicz, quoted in: D. Karaś, M. Sterlingow, Walentynowicz, op. cit., p. 235.